St Peter, Newton-in-Makerfield Celebrates ‘Railway 150’

Contents

| Plan & Key to St.Peter’s ‘Railway 150’ Exhibition. | 3 |

| A Message from The Bishop of Liverpool. | 5 |

| A Message from Lord Lee of Newton. | 6 |

| A Message from The Vicar. | 7 |

| ‘Railway gravestone’ verse. | 9 |

| A brief history of St.Peter’s Church. | 10 |

| The story of the opening of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, by Ian Singleton. (Manchester Grammar School). | 16 |

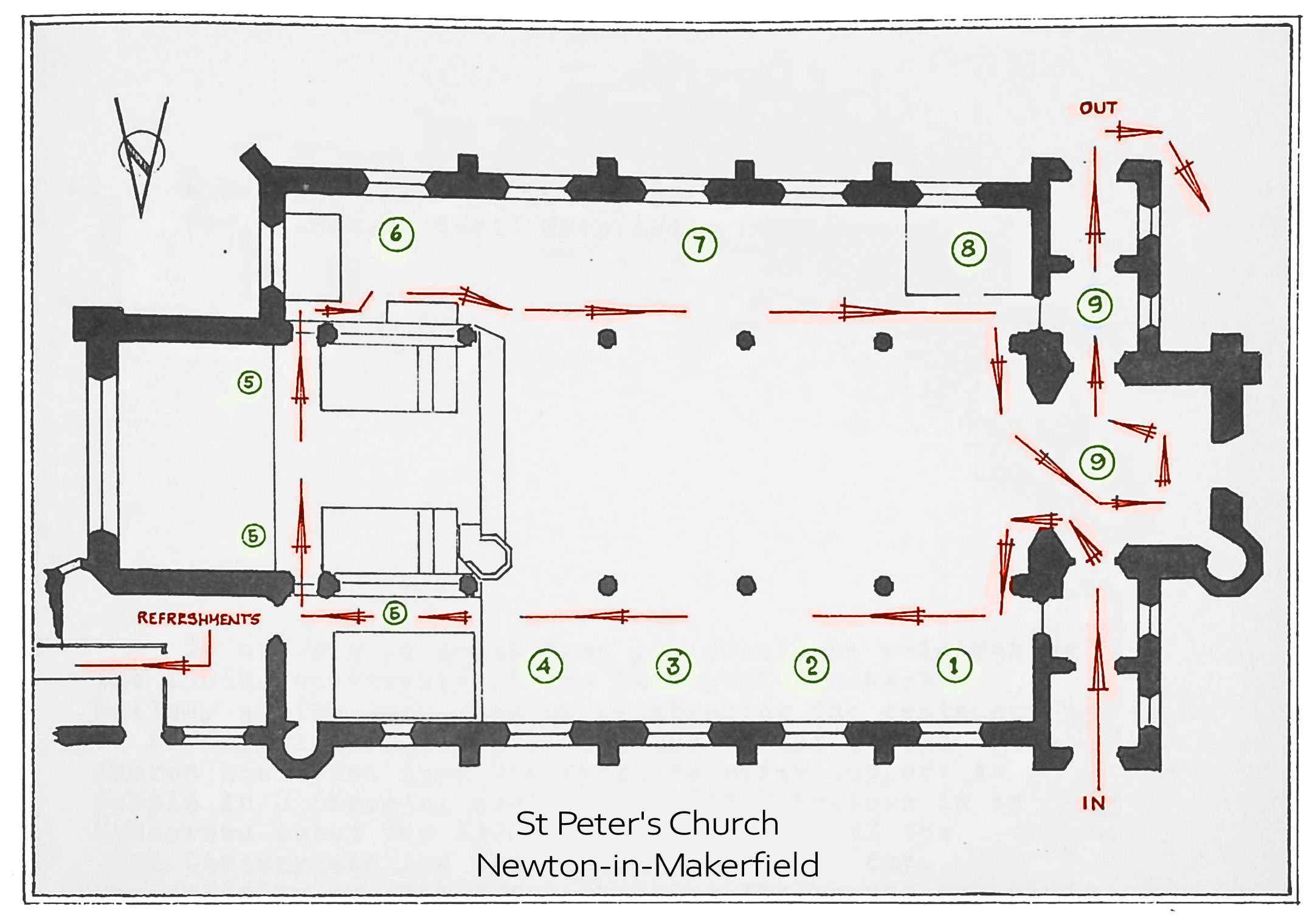

Exhibition Plan & Key

Floor plan of St Peter’s Church, Newton in Makerfield, showing numbered exhibition areas. Arrows indicate visitor flow direction, entering via “IN” at the bottom right and exiting via “OUT” at the top right.

| (1) | Steam Power. |

| (2) | Diesel Power. |

| (3) | Electrical Power. (Conventional fuel). |

| (4) | Electrical Power. (Nuclear fuel). |

| (5) | St.Peter’s School Displays. |

| (6) | Bookstall. |

| (7) | Model Railway Layouts. (Selwyn Jones School). (Wigan Model Railway Club). Railwayana. |

| (8) | Period Piece, Railwayman’s Cottage. |

| (9) | Floral Displays. ‘Rocket’. Huskisson Memorial, Etc. |

A Message from The Bishop of Liverpool

The Rt.Rev.d. David Sheppard.

It makes good sense that you should be celebrating the 150th Anniversary of the Liverpool-Manchester Railway at the same time as celebrating the centenary of Liverpool Diocese and 120 years of the school. The church has tried down the years to offer support to people in a changing world. The God I believe in is concerned about the Industrial Revolution of the 19th Century and the new technology of our day. Christianity is both about changing the hearts and minds of people from inside out and about changing the course of events so that schools, jobs and community life offer an enriching experience to all people in our society. It is good to be responding to the ancient call “lift up your hearts” this week.

A Message from Lord Lee

Ex-Minister of Fuel and Power.

The discovery of fire and the invention of the wheel enabled ancient man to begin the first elementary steps towards increasing his living standards.

Centuries later the first industrial revolution took place in this country and witnessed the application of energy and power to engineering techniques.

In the field of transport the steam age had begun. Stephenson, an engineer from Durham opened a small freight railway from Darlington to Stockton which pioneered the movement of goods by rail.

Having succeeded in this first venture he decided that human beings could also be transported by train, and the Manchester to Liverpool Railway was the result.

Today the manufacturing nations measure their living standards by the amount of energy and power they place at the disposal of their industries.

Our own township, in which Stephenson lived and worked during the building of the railway, has thus played a part in the creation of a development which opened up continents, and brought higher living standards throughout much of the world.

A Message from the Vicar of St.Peter’s

The Rev.d. Nial Meredith.

For over seven centuries our Church in Newton has stood beside one of the nations vital highways and has seen the many changes in modes of transport that have occured. A major change, and one which rapidly spread throughout the world, was the introduction of railways.

1980 marks the 150th anniversary of the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the first in the world to provide scheduled public transport between two major cities.

1980 also marks the Centenary of the Diocese of Liverpool, one of the cities served by that railway. I feel it is appropriate that, as our contribution to the Diocesan Centenary we should arrange an exhibition in Church to celebrate the opening of such an important railway with which Newton has such close associations.

This year our School will have provided education for children of the parish for 120 years. This service to the community will also be remembered in our celebrations and exhibition.

I hope the exhibition will convey the wider interests of the Church and its concern for all those engaged in railway work and that in illustrating mechanical power, it will lead us to think of Power in a spiritual sense.

‘Railway Gravestone’ Locomotive

This illustration of a railway locomotive is embossed on a grave stone in St. Peter’s churchyard. It commemorates the death of Peers Naylor, an engineer, at the early age of 29 in 1842. It is believed that he died in an accident.

Considerable erosion has occured so that parts of the locomotive are no longer visible. Efforts are to be made to prevent further destruction.

Beneath the locomotive on the stone appears this verse.

‘Railway Gravestone’ Verse

My engine now is cold and still,

No water does my boiler fill:

My coke affords it’s flame no more,

My days of usefulness are o’er.

My wheels deny their noted speed,

No more my guiding hand they heed.

My whistle, too, has lost its tone-

Its shrill and thrilling sounds are gone.

My valves are now thrown open wide,

My flanges all refuse to guide,

My clacks, also, though once so strong,

Refuse to aid the busy throng,

No more I heed it’s urging breath,

My steam is now condensed in death.

Life’s railway’s o’er, each station past,

In death I’m stopped and rest at last,

Farewell, dear friends, and cease to weep,

In Christ I’m safe, in Him I sleep.

A Brief History of St.Peter. Newton-in-Makerfield.

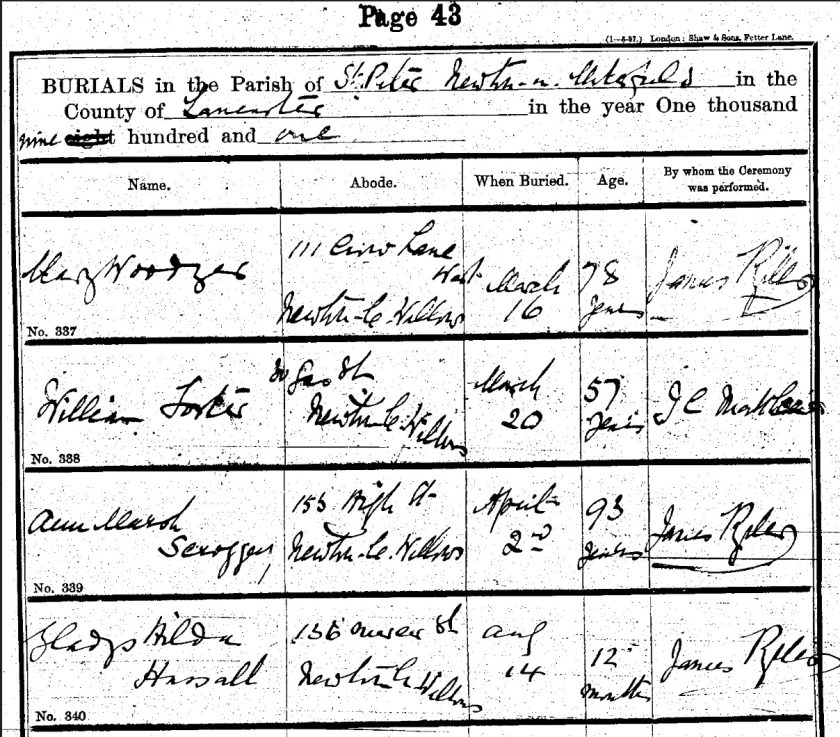

In 1242 Sir Robert Banastre, fourth Baron of Newton, erected a small chapel known as Rokeden on the site of the present church. Forty years later, on the plea of the long distance from the mother church at Winwick, a licence for the chantry to this chapel was obtained from the priors of St.Oswald’s at Nostell in Yorkshire. A chantry priest was appointed and Sir Robert endowed the chantry with lands in the township of Newton.

In 1405 a descendant of the Banastre family obtained from the Bishop of Lichfield a renewal and confirmation of the privilege of a chapel and further consent to have divine service celebrated without burden upon the mother church.

In 1433 the living was purchased from the prior and canons of Nostell by Sir John Stanley of Lathom and from that time the Newton Chapel and chantry came under the jurisdiction of the Vicar of Winwick.

On the suppression of the lesser monastries and chantries in 1553, the chantry services at the small chapel were discontinued and the endowment of £3-1-7d. became the nucleus of the present endowment of St.Peter’s Church. Incidentally, this amount is still paid by the Duchy of Lancaster to the incumbent of St.Peter’s.

In 1650 a larger building was erected on the site by Richard Legh who had purchased Newton from the Fleetwood family. At this time there were four chapels in the Parish of Winwick; Newton, Ashton, Lowton and Culcheth (Newchurch).

The chapel was enlarged in 1818 and again in 1834. The Rector of Winwick in 1841 finding that the chapelries under his jurisdiction had so increased that his four curates were unable to cope, resolved to make them separate and distinct. With the consent of the patron and Bishop an Act of Parliament was obtained under which Croft, Newton (Wargrave) and Culcheth (Newchurch) were raised to the dignity of rectories.

This act was supplemented by another in 1845, the terms of which, so far as they affected St.Peter’s were:-

“That it was expedient that such parts of the said parish of Winwick as were comprised in the several towns or townships of Croft with Southworth, Newton-in-Makerfield and Culcheth should be divided in three distinct and separate parishes for all ecclesiastical purposes.

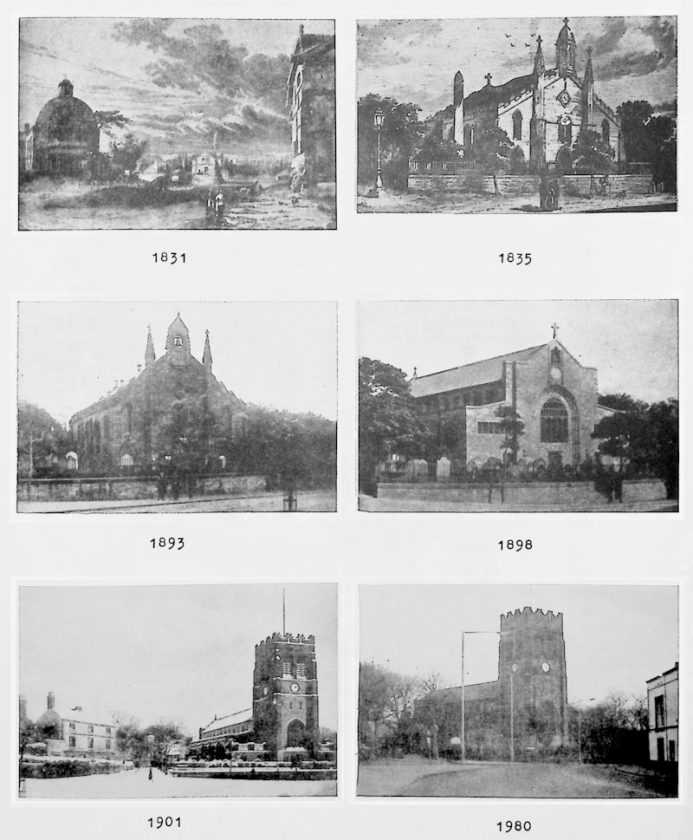

St Peter’s Church. Newton-in-Makerfield.

Photographs showing the evolution of St Peter’s Church across different periods: 1831, 1835, 1893, 1898, 1901, 1980

Having taken into consideration all the circumstances attending the newly formed parish of Newton-in-Makerfield, it appears to your Majesty’s said Commissioners expedient that a particular district should be assigned to the Chapel of St.Peter-at-Newton, situated in the newly-formed parish of Newton-in-Makerfield, and that such district should be named in the Chapelry district of St.Peter, Newton-in-Makerfield, with boundaries as described in such representation, and that banns of marriage should be published, and that marriages, baptisms, churchings and burials should be solemnised and in the said Chapel of St.Peter, and that the fees arising therefrom should be received by, and belong to, the minister thereof.”

In 1874 a movement for a new church was raised and eventually the foundation stone of the present church was laid in 1892. In 1893 the chancel was consecrated by the Right Rev.d. Dr.Royston, Assistant Bishop of Liverpool. The Building of the new church was completed in 1898. The architects were Demaine and Brierly of York. In 1901 the tower was added and dedicated by the Right Rev.d. Dr. Chavasse, Bishop of Liverpool. A small annexe, at the east end, was added in 1975 to provide meeting facilities.

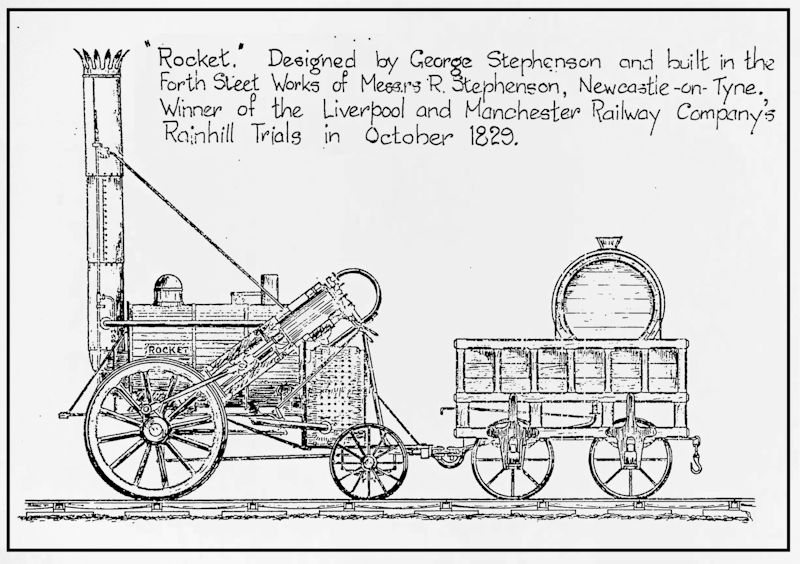

George Stephenson’s ‘Rocket’

“Rocket.” Designed by George Stephenson and built in the Forth Street Works of Messrs R. Stephenson, Newcastle-on-Tyne. Winner of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company’s Rainhill Trials in October 1829.

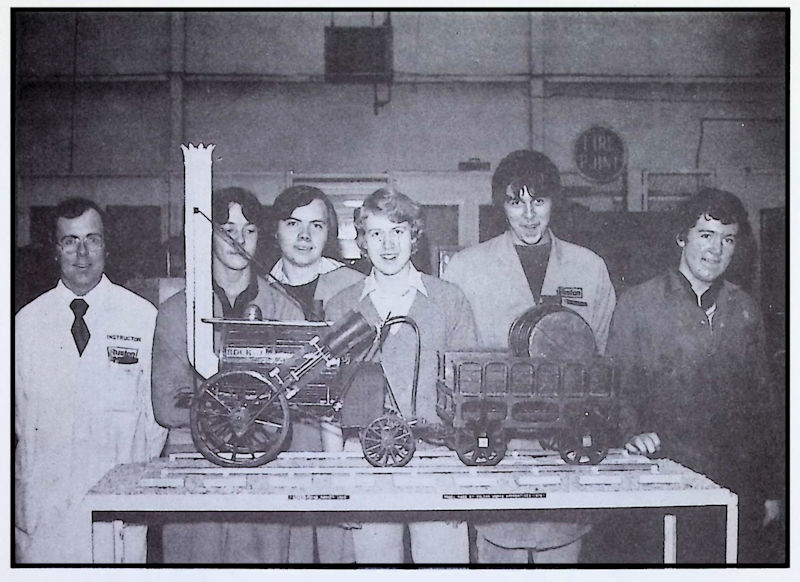

‘Rocket’ Model by Ruston Diesels Ltd. Apprentices

Model of Stephenson’s ‘Rocket’ built by a group of apprentices at Ruston Diesels Ltd. Vulcan Works.

Apprentices Ian Gravenor, Leonard Tickle, Robin Lear, Keith Rowlinson and Ian Jamieson with their Instructor Mr T.Bates.

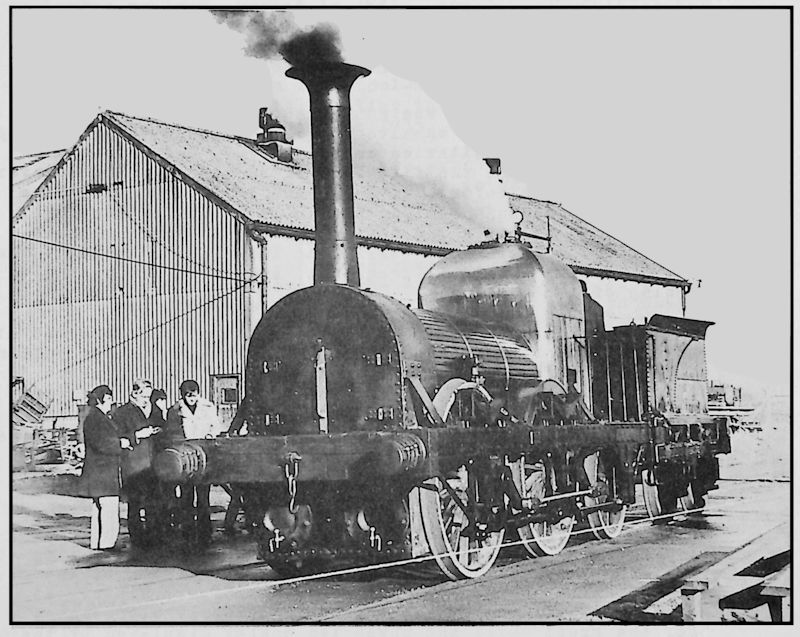

L&MR Locomotive ‘Lion’

‘LION’ Built for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1838, by Todd, Kitson and Laird of Leeds, together with a sister engine TIGER.

Sold by the L & N.W.R. in 1859 to the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board. Used until 1929 as a pumping engine at Princes Graving Dock.

Restored at Crewe Works to haul the replica L. & M.R. train at the Centenary Celebrations in 1930.

Starred in the film “Titfield Thunderbolt”.

Recently overhauled at Vulcan Works, Newton-le-Willows to take part in the “Rocket 150” celebration at Rainhill in May of this year.

The Opening of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway

by Ian Singleton.

At last, the line was completed. The jubilant directors organised a massive opening ceremony to which many of the nation’s dignitaries were invited. The date of the ceremony was set as the fifteenth of September 1830. However, some four months before, in June, the directors made plans for several excursions along the whole length of the line, primarily to practice the engine-drivers in working their engines and managing the carriages, but also to acquaint the general public with rail transport, and to advertise the opening of the railway.

On the 14th June 1830, a number of the directors met at the Liverpool tunnel and boarded the Arrow, which was pulling seven wagons filled with stone, a coach containing about 30 “other gentlemen”, and the directors’ coach, making a gross weight of thirty-nine tons to be hauled. The trip from Liverpool to Manchester took 2 hours 21 minutes, not allowing the twenty minutes delay incurred for attaching a second engine for negotiating the Rainhill incline, detaching this engine, and stopping to take on water at Parkside. This timing according to the Liverpool Mercury of the 16th June. However, the previous day’s Times gave a time of 2 hours 23½ minutes, with 15 minutes for stoppages. After inspecting the line at the Manchester end, a special meeting of the directors was held at the home of a Mr.Gilbert Winter, at which a vote of thanks was proposed to George Stephenson, “for the great skill and unwearied energy displayed by the aforesaid engineer, which have brought this great national work to a successful termination”.

The return journey took 1 hour 46 minutes, and the train reached Edge Hill, “to the applause of the large crowd there gathered”. It was on this run that the opening date was settled. However, before we progress, perhaps now is the time to tell the tales of the two men in the leading coach that day.

The first was Charles Tayleur. Tayleur or Taylaure, was a Liverpool engineer who is listed among the 58 proprietors of the railway in the Enabling Act of 1826. He was elected to the board of directors in February 1829, after the death of Lister Ellis. However, at the company’s annual general meeting on the 25th March 1830, Tayleur failed to be re-elected, losing his seat to David Hodgson, who was nominated by those proprietors who felt that a monopoly might be implied if the same board of directors was returned for the second year. However, in 1830, Tayleur founded the Vulcan Foundry at Newton-le-Willows (The foundry was so called because Tayleur’s emblem was Vulcan, the Roman god of fire). Tayleur bought up a village originally built to house the contractor’s men engaged on the construction of the colliery line which was replaced by the Warrington and Newton railway, opened in 1831. Tayleur renovated these cottages and sited his works alongside them. The works grew rapidly, especially after Robert Stephenson joined Tayleur in partnership in 1832. The works produced not only engines for the Liverpool-Manchester line, but for the St.Petersburg-Paulosk line in Russia, and a similar line in Austria as early as 1835.

However, Tayleur wanted to expand. In 1847, the Vulcan took over Bank Quay Foundry in Warrington, and it was here that the first iron sea-going ship was built in 1852. The ship, a tea-clipper named “Tayleur” was wrecked on her maiden voyage in the Irish Sea, with the loss of 450 lives, and it is claimed that this was the cause of Tayleur’s death. However the works he founded flourished and today provides marine diesel engines, used in many oil tankers and ships.

Another man on the train that day was to leave a much more obvious mark on the area. He was Hardman Earle, whose parents had been staunch critics of the line. However Earle served as a director of both the Liverpool-Manchester Railway and the North Union railway. A few years later, he became the manager and Chief Engineer of the London and North West Railway, and in about 1861 he became the director of the Viaduct Wagon Works, not a stone’s throw from the Sankey Viaduct. It was this works which constructed most of the carriages and wagons for the Liverpool-Manchester line. At about this time, the local station, which was variously named “Newton Junction” and “Warrington Junction”, took its present name, which soon spread to the whole town: Earlestown.

However, to get back to the account. During the summer several other excursions took place, and each proprietor was given two tickets for one of these trips. The trains were pulled by Rocket and Arrow, although as other engines arrived they were used too.

On August 21st, a sort of dress rehearsal for the opening day took place. More than a hundred Ladies and Gentlemen were taken from Liverpool to Manchester and back again in three seperate trains, pulled by Rocket, Arrow and Phoenix. Among the passengers were representatives of the proposed lines in the Birmingham and Sheffield areas, noblemen and members of Parliament. All were greatly impressed.

This rehearsal was repeated a week later, and again on 4th September, when a complete round trip was made, including stops for water and passengers, in less than five hours. The line was ready.

During early September 1830, several notices appeared in local papers, such as the Liverpool Mercury, to allay any fears that the public might have had of travelling on the train. One such entry guaranteed that the locomotive ran so smoothly that water would not spill from a wine-glass placed on the tail-board, and that those on the train would be able to read and write while travelling, as readily as in their own armchairs at home.

Another, citing the testimony of Dr.Chalmers assured aspiring passengers that even speeds of 34 mph could cause no inconvenience or alarm nor would the eye be disturbed “while viewing the scenery”.

However, contemporary physicians claimed that passengers would suffer effects due to “gravitational stress”. No man had ever travelled at thirty miles per hour before, and it was felt that it would be sheer folly to do so. Indeed, after the opening. Lord Brougham wrote in the Edinburgh Review, “The folly of 700 people going at 15 mph in 6 carriages exceeds belief”.

But just what was travel like on the first trains, and how did the passenger feel? Both these questions are answered in the letters of Fanny Kemble. She was not the first celebrity to travel on the foot-plate, another being Captain Scoresby, the noted circumpolar navigator, who timed the trains progress on the journey of the fourteenth of June.

However, Miss Kemble was better known for more cultural achievements. She had already won fame for her portrayal of Juliet on the stage at Covent Garden, and as she was playing in Liverpool at the time, she was invited by the directors of the line to travel on the footplate beside George Stephenson.

In her letters to her aunt, Mrs.Sarah Siddons, she gives a vivid description of what the driver would have experienced. (The Mrs.Siddons mentioned was, of course, the great tragic actress of the early 19th century).

Miss Kemble failed to find the success in her later years which she has enjoyed at the beginning of her career, and she left the theatre and opened a girls school in Bath. She married a wealthy American, and having emigrated to Georgia, campaigned for the freeing of slaves.

Here follows a selection from her letters, describing her experience –

My dear S.,

A common sheet of paper is enough for love, but a foolscap extra can alone contain a railroad and my ecstasies.

We were introduced to the little engine which was to drag us along the railways. She (for they make these curious little fire-horses all mares) consisted of a boiler, a stove, a small platform, a bench, and behind the bench a barrel, containing enough water to prevent her being thirsty for 15 miles.

The rein, the bit, the bridle of this wonderful beast is a small steel handle which applies or withdraws the steam from the legs or pistons so that a child might manage it. The coals which are its oats were under the bench. This snorting little animal, which I feel inclined to pat, was then harnessed to our carriages and Mr. Stephenson having taken me on the bench of the engine with him, we started at about ten miles an hour.

You can’t imagine how strange it seemed to be journeying on thus, without any visible cause of progress other than the magical machine, with the flying white breath and rhythmical unvarying pace between these rocky walls, which are already clothed with moss and ferns and grasses, and when I reflected that these great masses of stone had been cut assunder to allow our passage thus far below the surface of the earth, I felt as if no fairy tale was ever half so wonderful as what I saw. It was lovely and wonderful beyond words.

He explained to me the whole construction of the steam engine and said he could soon make a famous engineer of me, which, considering the wonderful things he has achieved, I dare not say is impossible.

At its utmost speed, thirty-five miles an hour when I closed my eyes, the sensation of flying was quite delightful and strange beyond description.

Kindest regards,

Fanny.

In the six weeks before 18th September, the final arrangements were made. Invitations were sent out to many of the leading political figures of the day, and almost without exception, these were accepted. The guest list included:

| The Duke of Wellington (Prime Minister) | Prince Esterhazy (Austrian Ambassador) |

| The Marquess of Salisbury. | The Earl of Cassilis. |

| The Earl of Glengall. | The Earl of Gower. |

| The Earl of Wilton. | The Earl of Lauderdale. |

| Viscount Belgrave. | Viscount Combermere. |

| Viscount Grey. | Viscount Ingestrie. |

| Viscount Melbourne. | Viscount Sandon. |

| The Bishop of Lichfield. | The Bishop of Coventry. |

| Lord Colville. | Lord Dacre. |

| Lord Delamere. | Lord Granville. |

| Lord F.L.Gower. | Lord Hill. |

| Lord Manson. | Lord Stanley. |

| Lord Skelmersdale. | Lord Wharncliffe. |

Other less prominent figures included the Rt.Hon.C.Arbuthnot, J.Calcraft and W.Huskisson,* Sir Robert Peel, General Isaac Gascoyne,* and the Boroughreeves of Manchester and Salford. *Both of these had been recently returned as Members of Parliament for Liverpool for their second term of office.

Also invited were various engineers, including Rastrick, Wood, George Rennie and Vignoles.

The remaining tickets were put on sale to the general public on the 2nd October, and they were readily snapped up by people who wished to share in the “extraordinary experience of the world’s first wholly mechanical railway being opened”.

Tradesmen in both cities prepared to accept the expected deluge of trade which would flood the area on and around the opening day.

Henry Kay, an hotelier on Wavertree Road in Liverpool advertised “Sitting apartments and Bedrooms furnished in the completest manner, including wines and spirits of the choicest quality”. Thomas Coglan, a sharebroker in Liverpool advertised some of the choicest seats on the processional train, at increased prices (the original tout?) as well as several shares in the company for sale.

J.Harding built a grandstand in front of his hotel in Liverpool, and William Lawton erected another beside the inclined plane at Sutton and promised refreshments, “a cold collation”, and good wines and spirits.

George Dean had yet another grandstand built for about 1,000 people by Newton Racecourse, and he too offered refreshments. The then editor of the Liverpool Mercury suggested that 15th September, or at least that afternoon, be regarded as a public holiday in Liverpool in order that everyone would be able to see some of the nation’s notables of the day. “All Lancashire was full of visitors, eagerly awaiting the event; Liverpool was unusually full, and bustle and pleasure seemed the order of the day”. (Liverpool Mercury 3rd September 1830).

However, one incident marred the preliminary celebrations. On 1st September someone opened a switch at Roby Embankment, causing Arrow and a line of coaches to be derailed, causing considerable damage, and killing George Stevenson (not to be confused with the line’s engineer!) Stevenson was one of the contractors engaged in the cutting of the Olive Mount excavation, together with his brother John. However, this setback was not large enough to dampen the spirits of the people, and excitement grew to fever pitch on Monday 13th September, when the celebration opening the Liverpool and Manchester Railway officially began. By noon on that day the number of tourists in the area had progressively increased and the Boroughreeves and Constables of Liverpool had a testimonial dinner on behalf of the Prime Minister, who had travelled up from London that day. By Tuesday night it was impossible to find anywhere to stay in Liverpool, so great was the attraction of this, a new concept in transport.

The Date of the Opening

However, at this point I would like to ask a question to which there are two possible solutions: What was the date of the opening?

This apparently silly question is not silly at all. On the engraving of the Moorish arch by Samuel Shaw, there is the title “The Opening of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, September 13th 1980. Several other contemporary sources give the same date. I, however, prefer the alternative, September 15th, for the following reasons:

i) The report of the opening ceremoney was printed in the Liverpool Mercury dated the 17th September. As this paper was printed every other day, on the odd-numbered date (e.g.13,15,17 etc) if the former date were correct, the report should surely have appeared in the paper for the 15th.

ii) The accurate description of the Liverpool & Manchester railway written by James Scott Walker was written on 13th September 1830, and contains no reference to the opening ceremony. This valuable little booklet is said to have been compiled with the aid of George Stephenson and to have been on sale at the official opening.

Its author, James Scott Walker, son of a Minister of the Church of Scotland, was born on Christmas Day 1793, in the village of St.Cyrus near Montrose. Orphaned at the age of six, Walker was educated by relations and led a roving life as a merchant’s clerk in the West Indies and Spanish America. In 1816 he published a dramatic poem on the great Caracas earthquake of 1812, to which he was an eyewitness. This started a correspondence with Sir Walter Scott, which lasted until Scott’s death in 1832. After working for four years as a merchant’s clerk in Liverpool he became the editor of a Chester newspaper in 1821, but returned the same year as the assistant editor of the Liverpool Mercury, and its companion weekly the Kaleidoscope or Literary and Scientific Mirror, a job which he filled for seven years. Walker filled minor posts until his appointment as editor of the Preston Chronicle in 1831. He died in 1850.

iii) As can be detected from other details Shaws etching is not terribly accurate.

The Opening Day

Long before seven o’clock on that fateful morning crowds had gathered at both ends of the line, and by nine o’clock at the best places at the company’s Liverpool terminus in Crown Street from where the procession would leave, had already been “bagged”.

The nearby grandstand rapidly filled, and the crowds extended at both ends of the line for seven or eight miles.

Soon after nine thirty the Marquess of Salisbury’s open carriage pulled by four grey horses swept into the Company’s yard, and from it descended the great Iron Duke, a sombre, unsmiling figure, still clad in mourning for the late king, George Fourth, and wrapped in a long Spanish cloak, a souvenier of his campaign during the Peninsular War.

As Wellington was arriving, the final train emerged from the tunnel beyond the terminus and took its position in the line.

The arrangements for the opening ceremony were very complex indeed. The Northumbrian, pulling the Duke’s coach, that holding a military band, and that of the directors their friends and families. This train was to be driven by George Stephenson, although it is more likely that he stood on the footplate and directed operations. The Duke’s train would travel alone on the south line, and the remainder would travel on the north line. This was so that the Duke could order his own train to be stopped and started at will, in order to admire the great engineering works.

Here follows a list of the other engines, arranged in the order in which they ran in the procession.

| Engine | Flag | Driver | Coaches towed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phoenix | Green | Robert Stephenson Jr. | 5 |

| North Star | Yellow | Robert Stephenson Snr. | 5 |

| Rocket | Light Blue | Joseph Locke | 3 |

| Dart | Purple | Thomas L.Gooch | 4 |

| Comet | Deep Red | William Allcard | 4 |

| Arrow | Pink | Frederick Swanwick | 4 |

| Meteor | Brown | Anthony Harding | 4 |

The idea behind the flags was to enable passengers to find their correct train. Each carriage carried a flag of the appropriate colour, as did each ticket, and the passenger merely had to match the colours in order to find his place on the train.

The Carriages

Just what did the trains look like on that dull, overcast day? One eyewitness says that there were thirty carriages of every variety, capable of carrying 772 people. Ericsson and Braithwaite failed to deliver the engines ordered of them and “several hundred” ticket-holders were left behind.

The carriages on that opening morning were a mixed collection indeed. The Ducal carriage, pulled by the Northumbrian, was built by Messrs. Edmundson’s of Liverpool.

The floor was 32ft.long by 8ft.wide, and was supported from 8 large iron wheels. The sides were beautifully ornamented, superb Grecian scrolls and balustrades, richly gilded, supporting a massive hand rail all around the carriage, along the whole centre of which an ottoman was the seat for the company. A grand canopy 24ft.long was placed aloft upon gilded pillars, and was so contrived as to be lowered for passing through the tunnel. The drapery was of rich crimson cloth, and the whole was surmounted by the ducal coronet.

The other carriages were of a less elaborate nature. For a description we must turn to Scott Walker’s Accurate Description.

First, the first class carriages: “The most costly and elegant contain three apartments, and resemble the body of a coach (in the middle) and two chaises, one at each end, – the whole joined.”

These are the second class: “Another resembles an oblong square of church pews panelled at each end, and the rail which supports the back so contrived that it may be turned over, so that the passengers may face either way, and the machine does not require to be turned. Besides these are others, of various grades of elegance.”

For the 1st class, a further description appears in the Manchester Guardian: “They have four seats in each compartment, and the contrivance by which one of the compartments is convertible into a big carriage ….. is a very desirable one to the invalid or valetudinarian whom necessity obliges to travel. The backs are taken out of the seats on one side, opening into a sort of boot lined with black leather and cushioned, and are then laid down across the space between the back and front seat, into which they fit, thus forming a complete bed. The cushions on the opposite seats are buttoned up and form a pillow; the legs are put into the boot, and the passenger may thus sleep or recline comfortable.”

However, it would seem that many of the first coaches were not too well constructed. They were extremely well constructed as far as decoration went, but their basic design was not good. They were very short, having a length of only seven feet between the wheels. This produced a see-saw motion when the coach was on the line, particularly when stopping and starting, and when the train picked up speed. The wheels too were crudely shaped at first. Made of iron they were constantly breaking, and George Stephenson ordered wooden spokes to be made for them.

The coaches were all brightly painted, and given such names as “Conqueror”, “Pegasus”, “Invincible” and so on.

It is probably true to say that the first coaches on that September morning were simply adaptations of Stage-coaches, and those people who had used stage coaches regarded trains as much the same thing, with people even travelling on the outsides of the trains, as can be seen on some of the etchings of the time. It was not uncommon for people to jump from a moving train to retrieve a hat, or to jump off and walk if the train had not arrived at their stop. It became such a problem that the L & M had to introduce a bylaw forbidding people to travel on the roofs of the coaches, as so many people were being injured in falls from the trains, or were crushed against an arch or bridge along the way. The first true railway was a dangerous thing on which to travel, for instance, during the first eleven weeks, a wheel of a carriage being hauled by North Star broke throwing three carriages off the line; an axle-tree of a tender broke while its engine was running backward throwing the workman onto the rails, where the train passed over his body and killed him; while another man who jumped from a carriage while it was still moving had his left arm so badly crushed that it had to be amputated. Yet as one mechanic put it “for one accident that happens by railway, fifty would by coach”.

The Departure

The opening of the line came at a difficult time for the North-West, both politically and economically, and the Duke of Wellington, as leader of those who had brought these troubles in the eyes of the public, was potentially at risk. Accordingly, many troops were drafted in to quell any riot which might spring up. These troops were very open to view, and with them came their full parade units and bands, and when the Prime Minister entered the yard, one of these military bands in attendance struck up “See the Conquering Hero comes”, and they continued to play until the trains had left the station. The Duke entered his carriage and, at ten o’clock the Northumbrian proudly moved off, its great lilac flag waving in the northerly breeze.

The Journey to Parkside

Parkside, where the trains would stop to take on water was some 17 miles away, and the journey was a picturesque one. The train rushed into deep chasm of the Olive Mount cutting, where spectators formed an “unbroken, many coloured, swaying fringe to the high skyline”. Again, crossing the Sankey Viaduct the banks of the canal below were thronged with people looking up. Everywhere crowds of varying sizes gathered at the best spots along the line, to cheer the array of visiting dignitaries. At the sites of some of the particularly remarkable engineering achievements, Wellington was heard to exclaim, “Tremendous” and “Stupendous” and “Magnificent”.

Passing through St.Helens Junction, a wheel of one of the trains on the north line ran off the track, forcing it to stop. The driver of the next engine in line, not realising what had happened, failed to stop in time and rammed the rear coach of the first train. No one was injured and after the wheel had been repaired, the procession continued.

Parkside was reached in four minutes under the hour, with average speeds of between 14 and 24 mph having been attained, much to the delight of the passengers. At Parkside it had been decided that the train on the south line would stop and others would steam past, after taking on water at one of the watering places, which stretched for one and a half miles along the line. Instructions both written and verbal, had been given to everybody that they must not leave their carriages. Despite this, many people including Holmes and Huskisson walked about along the line, congratulating one another on the great day and generally exchanging greetings.

During this time both the Phoenix and the North Star completed taking on water and passed by, continuing their journey to Manchester. Thus, the line was temporarily deserted. Holmes and Huskisson rounded the Ducal carriage and approached it, some say to greet Mrs.Arbuthnot, wife of fellow Tory M.P. and one of the finest political diarists in the early 19th Century.

However, it is more likely that the men did so to patch up their relations with the Prime Minister, an event which was desired by all Tories of the time, as this would give the weakened Government at least a hint of security.

The Huskisson Accident

The Duke, who in order to watch the by-pass was sitting in the corner seat of his state coach nearest the six-foot gap between the tracks, recognised Huskisson among the crowd milling around on the line, and acknowledged him with a nod and a motion of his right hand. At once Huskisson approached the carriage, and when the Duke had opened the carriage door, he extended his hand. Huskisson grasped it and a few words had been exchanged when several persons cried out warnings of Rocket’s approach on the north line. Having taken on water, the engine was continuing its journey to Manchester.

However, Huskisson was far from agile, and was also aging, being 70 at the time. (“Huskisson’s long confinement in St.George’s Chapel at the King’s funeral brought on a complaint ——– the effect of which has been, according to what he told Calcraft, to paralyse, as it were, one leg and thigh,”) (Thus wrote Thomas Creevy M.P. whose letters to his step-daughter, Elizabeth Ord, first published in 1903 as the Creevy Papers, shed much light on Georgian England), and he fumbled as he mounted the steps into the Ducal Carriage; it would seem that the approaching Rocket hit the open door and Huskisson fell to the ground. His left leg fell across the near rail of the track, doubled, and although Rocket Driver, Joseph Locke, made frantic efforts to stop the engine, Huskisson was unable to pull his leg back in time and the engine and the wheels of the first coach passed over his leg, fracturing his thigh and lower leg “in a most dreadful manner”. These events seem to have taken place just after half past twelve.

The Huskisson Memorial on the site of Parkside Halt, scene of the accident.

Hearing the cry “Get in, Get in” those who were on the line took up a variety of positions; two of Huskisson’s companions, Holmes and Birch, flattened themselves against the side of the Duke’s train, another, the Rt.Hon.J.Calcraft climbed into one of the compartments while Prince Esterhazy, a small lightly built man was hauled bodily into another. Huskisson turned and crossed the line, confused, hoping to lean against the steep embankment there. However, because the bank was so steep and the clearance so small (there were also large pools of water between the north line and the bank) he retraced his steps, apparently in the hope of climbing into the Prime Minister’s carriage through the open door. Indeed the Prime Minister called out, “Huskisson, do get to your place! For God’s sake get to your place!”

The train was stopped at once, and Holmes, the Earl of Wilton and Mr.Parkes, a solicitor from Birmingham, hauled the injured man from beneath the engine. At once he was heard to groan “I have met my death”. He was carried across to the Northumbrian, and at the same time a handkerchief was wound round his thigh as a torniquet. Amidst the general confusion which ensued, it was George Stephenson who took control. He uncoupled the first carriage behind the Northumbrian, which contained a military band up to that time and loaded into it Huskisson, his wife “wailing most pitifully”, the Earl of Wilton and two doctors. He personally drove the train “at a good speed” and the Northumbrian reached Eccles, a distance of 15 miles, in 25 minutes.

If you look in the Guiness Book of Records at Progressive British Steam Locomotive Speed records, the second entry is for that memorable journey. A speed of 36 mph. is recorded. And yet just five years before, men had feared travelling at ten mph! As Smiles wrote later “This incredible speed burst upon the world with a new and unlooked for effect”.

The Death of Huskisson

Eccles was reached shortly after one o’clock and Huskisson was carried to the Vicarage on a couch.

There after much discussion among the doctors present (including several who were brought out from Manchester), it was decided not to amputate the leg. The bones of the lower leg had been broken into small pieces, the thigh bone was fractured into several fragments, and the muscle was badly mangled.

The Vicar read from the Book of Revelation, and then administered the Sacrament; Huskisson dictated a codicil to his Will, which was witnessed by the Earl of Wilton and Lord Granville and Colville. He was now in great pain and sinking fast. His last words were, “The Country has had the best of me. I trust it will do justice to my public character. I regret not the few years which might have remained to me, except for those dear ones whom I leave behind me”. He died early that evening, before seven o’clock.

The Decision to Continue

Meanwhile, the tragi-comic drama developed at Parkside. After the initial shock of the accident, the dignitaries were unable to decide what should be done. Wellington and Sir Robert Peel said that they were in favour of returning to Liverpool, saying that they had seen enough of the railway and its accessories to retain a most favourable impression. Many others agreed with them.

However, most of the directors urged that this proposal be reconsidered saying that they had an obligation to the shareholders and to the general public to complete the ceremony, despite the accident. However, it was a magistrate called Hulton and the Boroughreeve of Manchester, Sharpe, who finally got this decision reversed. Sharpe in particular pleaded with the Prime Minister. Citing the general unrest in the land, he said he could not be answerable for the peace of his city if the trains did not enter the city. The masses were waiting and if nothing appeared, rumours would fly, either that some terrible disaster had occured or that the Prime Minister was afraid to face his people.

“Something in that” said the Duke, tersely in answer, to which Peel added “Where are these Directors? let us see them”.

So it was decided to continue, but in view of the tragedy, the band should be returned to Liverpool, the buglars assigned to each train should be silent, and the passengers should be requested not to respond to the cheers of the crowd.

Since Northumbrian had been sent off to Eccles, there was no engine to pull the Ducal Train, and no engine could be crossed over to the other line. After more debate, the two leading trains on the north line, pulled by Phoenix and North Star, were coupled together and from their rear a chain was attached to the State carriages on the parallel line.

The Journey to Manchester

The procession continued in this comical manner to Eccles, where the inquiry was made of Huskisson’s condition (and no doubt, when Granville and Colville witnessed the addition to Huskisson’s will), here also Northumbrian and the single carriage were re-attached. By now all the engines were getting low on steam despite having re-watered yet again at Parkside during their one and a half hour halt while the great ones had decided on continuing.

It was about a quarter to three as the trains rumbled into Manchester, but the procession was not greeted with cheers and applause, but with the sullen roar of an angry mass, poised on the brink of violence. The 59th regiment were out in force, as were the police, but they failed to control the mob.

Forced to reduce speed to avoid more bloodshed on the railway, the crawling trains became easy for the abuse and brickbats of the crowds of working people, who showed their opposition to Wellington by hoots and catcalls, by wearing tricolour hats, and simply by standing in silence as the Duke’s carriage passed. Cries of “Remember Peterloo” rang out from the crowds of workers.

As the trains entered the Liverpool Road Station, at about half past three, the crowds rushed the station and the police could not hold them back. Chaos prevailed. Few passengers fought their way through to the new goods warehouse where lunch awaited them. The Duke refused to leave his carriage for about an hour, but he shook hands with his well wishers, and even kissed several babies until his train pulled out of the station. Indeed, the Duke’s carriage became such an uproar that Lavender, Manchester’s Chief of Police, struggled through the throng to urge an immediate departure, otherwise, he confessed that he could no longer answer for what might happen.

The Northumbrian was brought round the State train and the Duke beat an orderly retreat, less sure that his opponents were a few mere agitators.

However, again the Directors’ plans fell apart. In the general confusion, they had forgotten that Dart, Meteor and Phoenix had also crossed over to the south line to run out to Eccles to re-water, and Northumbrian encountered these as they were returning to Manchester to pick up their trains.

To return back into Manchester would be unthinkable, so the four engines would have to run to Huyton in front of the Northumbrian, leaving the seven crowded trains in Manchester to be dealt with by Arrow, North Star, and the Rocket. These three still had to get clear of their trains and run to Eccles to re-water. This took some time, and by the time they returned, the autumn evening was closing in and it had started to rain, damping the spirits of the already dejected passengers. Meanwhile the Duke’s train continued at a great speed, and Wellington and his party left the train at Childwall Hall, near the Roby embankment, in order to visit the Marquis of Salisbury, and it was seven o’clock before the Duke’s train reached Liverpool.

The Return to Liverpool

Back in Manchester, Locke, Stephenson and Swanwick, undismayed by the chaos and confusion around them, succeeded in getting all the trains marshalled together with the three engines at the front, as it had been decided to run one long train in the adverse conditions which prevailed.

Slowly the three engines managed to start, a job which was made more difficult by the sand and earth trampled on to the rails by the mob.

The trains stopped at Eccles so that inquiries could be made about the injured Huskisson, and it was at this time that the public came to know that he was dead.

In attempting to re-start, two couplings at the head of the train snapped under the strain, but the crews lashed the train together with ropes and then continued.

At Parkside a lantern waved on the line ahead; it was three of the locomotives Dart, Comet and Meteor, which had crossed over at Huyton and returned to help. The fourth locomotive, Phoenix, had gone ahead as a pilot to the Northumbrian.

The Dart and Meteor were coupled on to the long train, while Comet ran ahead by about half a mile, looking out for obstructions, her fireman holding aloft flaming lengths of tarred rope to light the way. The Comet’s only unexpected encounter was with a wheelbarrow which splintered harmlessly under her driving wheels. Under the adverse conditions, the train could not climb the Whiston Incline, and all male passengers had to be ordered out of their seats to lighten the load. However, once over, the journey was easy, and the Liverpool terminus was reached at 10 p.m. where the weary passengers “were much heartened by the cheering of the crowds who had waited patiently in rain and darkness for their return. As the carriages were attached to the incline rope and lowered down the long tunnel to Wapping, the passengers cheered, and as the echo of their voices and the rumbling of the wheels grew louder, so the shouts were taken up by the waiting crowds at Wapping.

It was 11 o’clock before the last passenger left his carriage and staggered home to bed.

The following morning the Northumbrian set off for Manchester with a load of 130 Quakers going to a prayer meeting in Manchester. The Liverpool and Manchester railway had begun.

(Huskisson’s body was taken to Liverpool on 18th September and the funeral was held on Friday the 24th, with an estimated 15,000 – 20,000 people attending).

A coroner’s inquest was held the morning following the accident and the jury, after hearing the Earl of Wilton’s testimony, returned a verdict of “Accidentally killed”.

Acknowledgments

The organisers wish to express their thanks and gratitude to all the individuals and organisations who have contributed to and assisted in the preparation of St.Peter’s ‘Railway 150’ Exhibition and the associated events.