Burtonwood is a village between the towns of St Helens and Warrington, whose history stretches back into the thirteenth century and probably further. The population has always been small in number, yet Burtonwood, for such a small village, is well known for two phenomena: its American connection and its beer!. Burtonwood parish is a mixture of old and new. From a small rural community of a few scattered farms and cottages it grew into a village and later became a strong farming community and then came the brewery which still produces excellent beer.

It has seen the rise and fall of coal mining, within walking distance were once Clock Face, Collins Green and Bold collieries. The first two have long been closed and Bold has now followed. There was once a railway station at Collins Green, a working canal behind Bradlegh and later an important military airport at Burtonwood (which is now known as Callands), the M62 and mining subsidence put an end to any hopes of developing it as a civil airport.

Engineering briefly prospered in the village, but the Brewery remains as the only major local employer, although farming is continuing to thrive. The community that has in its time welcomed such diverse newcomers as starving Irish and, seemingly well fed G.I.s, with traditional Lancashire tolerence, now finds itself by some irony and a bureaucratic whim, transported to the county of Cheshire, but in the hearts of the villagers, Burtonwood will always be in Lancashire.

The long established villages of Burtonwood and Collins Green, and the rapidly expanding industrial and leisure centres on the World War II American air base mean that the council meets at alternate locations so that parishioners can easily attend and observe.

Burtonwood village has several small shops, three pubs – The Bridge Inn, The Elm Tree Inn and The Chapel House (Pubs), three churches – St Paul of The Cross (Roman Catholic), St Michaels (Church of England) and The Methodist Church and there are two schools – St Paul of The Cross and Green Lane School.

There is a thriving Community Centre and clubs at St Michael?s Church Hall and the Catholic Club. Sport is an important part of village life and the parish council provides facilities for rugby, bowls, football and cricket, as well as a playground for the children.

Callands, the area which occupies the area of the old air base, is a thriving mix of industry, housing and leisure facilities, one of the key growth points in the entire district.

Early Burtonwood

In the late medieval period Lancashire was a very sparsely populated county, notoriously poverty stricken with inadequate communications. In 1291 there were only 56 parishes in the county, some covering several townships and their number was to remain relatively unchanged for almost 400 years, although the population increased and dependent chapels were often built. Burtonwood was not to be a parish in its own right until 1650 and so prior to this the local manors of Bold, Bradley and Bewsey were considered more important and are more often mentioned.

Before the Norman conquest, it was probably known as Burton and almost certainly acquired the name Burtonwood when it was included in his forest by Henry I. The spelling wasnt standardized, being known as Burtoneswood in 1228, Bourtonewood in 1251, Burtonwode in 1297, Burtounwood in 1337 and Burton Wood in 1604.

Burtoneswood was perambulated in 1228 in accordance with the Charter of the Forest and its boundaries were defined as from – Hardsty in the west to Sankey Brook in the east, and from Bradley Brook on the north to Ravens Lache on the south The timber therein was reserved for building and for fuel, for William le Boteler, Lord of the Manor of Warrington. The land itself passed briefly into the hands of the Earl of Chester in 1229 and subsequently to William de Ferrars, Earl of Derby. In 1251 de Ferrars granted some land in the hey of Burtonwood to the Abbey of Tiltey in Essex. As well as the land this included licence to construct two water mills and weirs on the waters of the Sankey. The monks gave this land the name of Beau Site, a name which became Beausse in 1313, Beaussee in 1368 and eventually Bewsey.

In about 1264, Robert de Ferrars sold the manor of Burtonwood to William de Boteler for 900 marks which was to be paid in installments of ?10 per half year. However, le Boteler seems to have experienced some difficulties with his hire purchase repayments for in 1270 he still owed 460 marks and ten years later he was released from his arrears by the assignees of Robert de Ferrars. By 1337 Burtonwood was described as “neither a vill or a hamlet” and though it still contained much woodland it was becoming more and more cultivated. This was the result of the cunning of the Lords of the Manor who granted tenancy of land only for the duration of the life of the tenant, hence more and more areas of cultivated land accrued to them on the death of these tenants; land which, being cultivated, had greatly increased in value.

On the opposite side of Burtonwood to Bewsey lay the manor of Bradley where the Haydock family lived for centuries. In 1336 William de Boteler leased to Gilbert de Haydock and his son Matthew, for the duration of their lives, some land on the western side of their field called Pikiswood, another plot of wood and waste on the southern side of Sanki Bonke, all lying in Burtonwood, with liberty to clear the land of trees and cultivate it. Some twenty years later Sir William de Boteler granted to the de Haydocks all the land and tenements which they held for him in Warrington, Great Sankey and Burtonwood in exchange for certain lands which had been the subject of a dispute between the two families. In 1386 Bradley Hall, in common with many other manors throughout the country, held a licence for the celebration of Mass and when Joan Haydock married Sir Peter Legh of Lyme, it passed into the hands of the Legh family where it remained until the 19th century.

It seems that in the history of the Legh family at Bradley all of the heirs were named Peter and it was Peter, son of Peter and Joanne de Haydock, who rebuilt much of the Hall and left this description in 1485:-

“The aforesaid Peter Legh holds the manor of Bradley in the vill of Burtonwood – that is to say a view hall with three new chambers and a fair dining room, with a new kitchen, bake house and brew house, and also with a new tower built of stone with turrets and a fair gateway, and above it a stone Bastille well defended, with a fair chapel, all of the said Peters working, also one ancient chamber called the Knyghtes Chamber, all which premises aforesaid with other different houses are surrounded by a moat with a drawbridge and outside the moat are three great barns, namely on the north side of the said manor house with a great shippon and stable with a small house for the bailiff and a new oven built at the eastern end of the place called the Parogardyne”.

The Peter Legh who gave the description of Bradley also supported the Duke of Gloucester, who later became King Richard III. The King granted him ?10 per year for life in consideration of his services and is also reputed to have been his guest at Bradley. In the present Bradley Hall Farm is a curious old oak bed, of the 15th century, put together with wooden pegs in place of nails or screws, with four low bedposts, and known as “The Kings Bed”. Lady Leghs history of the Legh family gives credence to the legend that this indeed was the bed upon which Richard, Duke of Gloucester, slept when he spent the night at Bradley on his march through Lancashire to repel the Scots in 1482.

The third of the notable manors in the area was Bold, where the Bold family is recorded in 1201. Around 1254, William Bold received grant of the manor of Bold from William de Ferrars. The land of William de Bold went up to and included Haley Head in Burtonwood, hence the township was surrounded and overlapped by the three manors of Bewsey, Bradley and Bold. The le Botelers of Bewsey assumed the title of “Lords of the Manor of Warrington and Burtonwood”, and so despite its comparative obscurity, it was represented at some of the great events in English history. Successive Lords of the Manor were recorded as having been present at Caernavon when the first Prince of Wales was presented, and at the battle of Crecy with the Black Prince. In 1492, John de Bold and his son Thomas fought with the Prince of Wales against Owen Glendower, for which John was knighted – two years later he was granted a licence by the king to impark 5,000 acres of land at Bold and in 1406 he became High Sheriff of Lancashire.

However, it was at Agincourt that the area seems to have been most strongly represented for, in addition to Sir John le Boteler and Thomas Bold of Bold, it is also recorded that Sir Piers de Legh of Lyme, Bradley and Haydock, was wounded. It is worth noting that each of these three local dignitaries would have taken a retinue of men which more than likely included many from the locality.

Soon after 1483 Richard Bold married Margaret, daughter of Thomas Boteler of Bewsey, and as time went by, the power of the Bold family increased. In 1597 Richard Bold, along with Thomas Ireland, purchased the Bewsey estates and in 1612, when Sir Thomas Bold the illegitimate heir of Richard, died, he was described as holding the manors of Bold, Burtonwood, Sutton, Great Sankey and North Meols. Four years later, his son married Ann, daughter of Sir Piers Legh of Bradley Hall and together they were responsible for the restoration of Old Bold Hall. But the religious conditions which prevailed at the time of the restoration of the Old Hall were very different to those which prevailed when it was first built.

Reformation and Recusancy

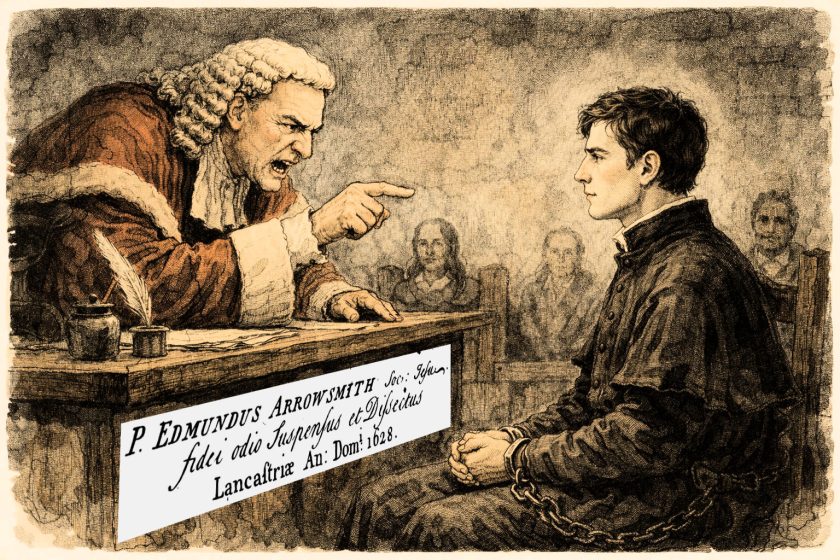

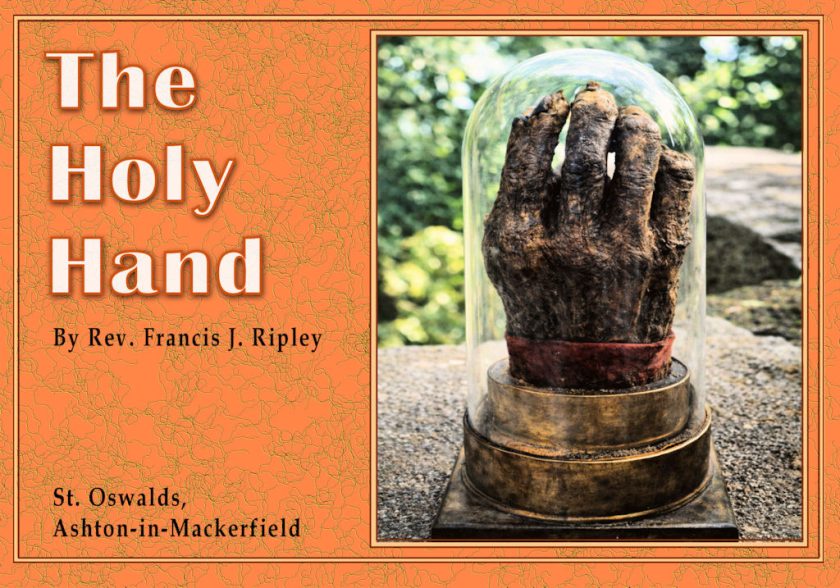

By the middle of the 16th Century the reformation had not only shattered the thousand-year old English communion with Rome, but it also disturbed the status quo of everyday village life and brought hardship to the many who refused to attend the services of the Church of England as established by the 1559 Act of Uniformity. Reaction to the Act was far from uniform, especially in some parts of Lancashire. Christopher Thompson, a young Anglican clergyman, was removed from his rich rectorship in Winwick in 1575 for frequenting the company of the many notorious local papists and teaching unsound doctrine against the laws of God and this realm and uttering pernicious and papistical doctrine. Soon afterwards he went to the seminary at Douai where he was ordained and returned to England to become one of the Douai seminarists to work in Lancashire.

In 1582 Bold Hall was singled out as a place where secret masses were said one , Holland of Sutton (Ven. Thomas Holland – Son) and his wife used to come often…even if he were not a recusant himself. A recusant was the term for someone who refused to conform to the Act of Uniformity. Robert Ogdeyne, who was a servant of Richard Bold, gave information about clandestine masses at the hall when Richard Smyth was the priest in 1588. The deponent went on: He never saw the priest (Richard Smyth) but one time and that was as he came over the dam-head at Bold, and three or four with him, and was cunningly conveyed in at a back gate into the garden and so over the drawbridge and into the house. It was also claimed that neighbours used to come to Bold at such times as other men go to church. In 1592 Bold of Bold was described as a Releever and Favourer of Jesuit and Seminary priests and again in 1604, Bold! obstinate recusants there in the late Queens time. An obstinate recusant was one who had not attended the Anglican service for over a year. Among the list of recusants in this 1604 document is Francis Worsley, his wife and all his household, vehemently suspected to relieve and mayntayne his brother a priest and William Tarbock, yeoman, late of Ditton, now dwelling in Burton Wood and vehemently suspected to be lately married by a popish priest.

Bold lay in the chapelry of Farnworth in the parish of Prescot, whilst to the other side of Burtonwood lay the notorious parish of Winwick which contained a recorded 127 recusants in 1604, with three priests serving the Winwick, Wigan, Prescot area. On Good Friday of that year, 100 attended mass there, donating ?4 in the collection for the celebrant. In 1590 the Bishop of Chester had written that the numbers of recusants is great and doth dailie increase…the papists are everywhere grown so confident that they contempue the magistrates and their authoritie, but, if a congregation of 100 could scarcely have gone unnoticed, it must not be assumed that the three priests were totally safe to contempue the authorities. They each had a pistol-carrying bodyguard to defend them from capture and were frequently made aware of just what capture would entail: in 1615 John Thulis, an Upholland-born priest, was hanged, drawn and quartered in Lancaster and his quarters were exhibited in four Lancashire towns, Lancaster, Wigan, Preston and Warrington.

In 1559 the fine for recusancy was 12d. per days absence without good excuse from the Anglican service. This was later raised to ?20 per month, the revenue from which was shared between the Exchequer, the Poor of the Parish, and the Informer. A variety of sanctions were imposed on the Catholics including double taxes and sequestration of lands and in 1652 the Hollands, who had frequented masses at Bold Hall, had their lands sequestrated for recusancy, whilst in 1655 the lists of recusants under the sequestration included – Margaret Johnnes of Bold, Widow. Isabell James of Bold. Joan Bold of Bold.

But the Bold family did not remain recusants and in 1605 Thomas Bold founded the Anglican church in Burtonwood, called Windy Bank. The first minister was Mr. Thomas Hindle (1505-23) who is buried in Winwick churchyard. During the Commonwealth Period Burtonwood was separated from Warrington and made into a parish in its own right. It is interesting to note that the Rev. Samuel Mather, who sailed with his father Richard in 1635 to join the Pilgrim fathers in America, became minister of Burtonwood for a short time after 1660, so he must have been the first American in the village!

However, it was not only the Catholics who were experiencing religious turmoil and in 1690 another place of protestant worship was opened in Burtonwood. A certificate was granted in Ormskirk, July 20th, 160, stating that the house of Peter Gaskell in Burtonwood is now certified for a meeting place for the congregation of Protestants dissenting from the Church of England for their religious worship. Peter Gaskells house was known as Red House Farm in Hall Lane, which is now a peaceful country road, but at that time was an important route to Bradley Hall.

Even in the next, however, the law still militated against Catholics. In 1717 a list was drawn up of all Papists Lands in England. Included in the list was John Chaddock of Burtonwood, Husbandsman. Still later, the returns of Papists of 1767 lists fifteen Catholics in Burtonwood, whilst the same return for New Peter Street, Liverpool includes: John Webster, a tailor aged 52 from Burtonwood. Henry Houghton, a tailor, from Burtonwood.

The Eighteenth Century

Knowledge of everyday life in the village in the village in the 18th Century has been somewhat obscured by a lack of contemporary records but comparatively recently the Constables Book for 1721-1864 was unearthed from amongst the Parish Council records. The Burtonwood Constables Book is a remarkable document and here are a few references from it to give a glimpse of a few aspects of what parish life was like in the 18th Century.

At the beginning of the 18th Century the majority of Englishmen still lived in villages and, though the seat of government still rested firmly in London, the dogs life of government was carried out in the villages themselves. Every householder who was not specifically exempted by Parliament was compelled to serve his time at one of the parish offices and the most ancient of these offices was that of the constable who was appointed annually at the Court Leet at Bold Hall and whose numerous duties included, reporting all crimes, and the serving of warrants and summonses. Since the office was unpaid and obligatory, it could sometimes be as unpopular with the officeholder as with his clients.

In 1736, at a towns meeting held at the Chapel House, Richard Taylor, the schoolmaster, was appointed to keep all Log Books Assessments and Indenture and to draw up and copy all officers accounts. The officers were strictly forbidden to keep their own accounts and to discourage this, even if they did, Mr Taylor would still be paid as if he has really written and done it. The amount that each officer was allowed could never exceed 6s.8d. (34p), so it demonstrates an extremely rigorous attitude to public accounts.

A similar, somewhat puritanical approach to public office is demonstrated by the meeting of 1738 which, whilst allotting the said schoolmaster 40s. (?2) for stamps, paper, etc., for use in the keeping of his books, adds that this should only be paid as long as he shall abide in the town and behave diligently and not neglect his business upon trifling occasions.

In this same meeting of March 31st, 1738, it was decided that all person who are found guilty of any crime or misdemeanor shall be prosecuted at the expense of the town, but this firm commitment to law and order seems to have run into some practical difficulties for on November 3oth, 1738, it was determined that this would not apply to persons of ability to pay they shall be apprehended, and shall pay the expense themselves. Presumably, the better-off criminal would now pay for his own arrest. It was obviously a troublesome business and the whole thing was rescinded in 1741 as being prejudicial to the town on several accounts but there is no mention of whose accounts they were.

Some 30 years later in 1777 (when elsewhere they were concerned about the American War of Independence) Burtonwood was still worrying about its crime rate. Because of frequent thefts, robberies and felonies committed within the township of Burtonwood and the offenders not properly sought after and brought to justice through fear of the extraordinary expense, it was decided that in future the town would again defray the expenses of apprehending and prosecuting the offender so that the constable with the full vigour of the law, would be encouraged to proceed against those who stole cattle, goods, chattles and effects.

Yet this evident progress in the cause of justice is somewhat tarnished to our modern eye when we learn that this should not extend to Persons having goods, chattels and effects stolen (presumably they had no cattle) who are paupers, inmates and persons inhabiting houses, rooms, cottages, dwellings which are not rated (It must be remembered that the 18th Century law was not so much to protect the poor as it was to protect property).

This 18th Century attitude to the poor is further evident in a reference to the homeless or vagrants. At the time the upkeep of the poor and homeless fell upon the parish in which they resided and so it was common practice to deal with tramps and vagabonds by getting the Constable to kick them out, over the parish boundary and into the responsibility of the next parish. He should never encourage them to stay by adopting the charitable approach. It is no surprise therefore that we find in Burtonwood in 1738 No Constable in the future will be allowed anything for Vagrants in his accounts.

At the public meeting of November 12th, 1746, the subject was Bonfire Night, a public rejoicing day: it is agreed that whereas a custom has prevailed for some money to be spent on November 5th at other houses than this house viz. the Chapel House, that for the future no money be spent on November 5th at any other house than the above house and also that above the sum of five shillings shall not be spent on the 5th November, but only coals and powder be allowed over and beside the same. It is not known why the decision to cut down on the expense of November 5th was taken. Since the meeting was on November 12th, then it is almost certain that the recent public rejoicing had been too extensive and too expensive and the year of 1746 suggest a reason. The intensity to which Guy Fawkes Night was celebrated would vary from time to time but since it was still very much an anti-papist event then the popularity of the Catholics, which ebbed and flowed with each popish plot would have an effect upon it. Traditionally the Catholics supported the Jacobite cause and Bonnie Prince Charlies 1745 rebellion, when passing through Lancashire, was joined by two hundred Lancashire Catholics at Manchester en route to Derby. An entry into the Constables Book for 1745 shows that Burtonwood contributed militia and arms to the cost of ?26, a considerable amount for a small village, but then the rebellion had come pretty close. Maybe that is why, just a few months after the defeat of the Young Pretender at Culloden, the celebration of the 141st anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot seems to have been too expensive for the keepers of the public purse.

In the second half of the 18th Century a small but nevertheless significant addition to the traditional rural and agricultural trades seems to have appeared in the village with several instances of the craft of clock and watch making appearing, one of whom lived at the Moat House. In the 1767 list of Papists in Burtonwood (Map 1786) is Thomas Allcock, aged 20, who is described as a watchmaker, whilst the list of St Helens clock and watchmakers includes: 1783 James Houghton – Burtonwood/Rainhill, Watch Movement Maker. 1784 Henry Roughley – Burtonwood/St Helens, Watchmaker of Parr. 1793 – Bold, Watchmaker.

The Nineteenth Century – Immigration & New Occupations

The population of Burtonwood at the beginning of the 19th Century, stretching as far as Dallam and Bewsey Old Hall, was 773, but by the end of that century it had risen to 2,187, a threefold increase which obviously brought with it great changes. Yet this growth was nothing compared to the neighbouring villages of Sutton and Parr which rose nine and eleven times respectively, thus changing pleasant villages to urban sprawl within a few generations. Mr Bryce for the Taunton Commission in 1868 was to liken this rapid expansion from the thinly-peopled places of barely a century ago, to the sudden growth of colonial settlements in Australia or the Wild West : From Burnley to Warrington, from Wigan to Stalybridge, it is one huge congeries of villages, thickening ever and anon into towns but seldom thinning out into anything that could be called country.

And yet Burtonwood (Map 1829) was one of the few that retained a rural air. The Tithe Map of 1839 shows it as an area almost exclusively dependent upon agriculture. the principal landowners were Thomas Legh Esq., Lord Lilford and Sir Henry Bold Houghton (the owner of Bold Estates), and the occupiers and tenants of that land include many old Lancashire names still in the village today – Fairclough, Orford, Naylor, Bate, Forster, Kilshaw, Makin and Woodward. A certain Mr James Bridge kept the diary and the intriguing Culcheths Tenement of Cottages and Gardens was occupied by James Medowcroft and others.

But it its the Census of 1851, and even more that of 1861, which shows just how the village was beginning to change. In 1851 when the population was 831, many were still employed in the traditional rural and agricultural occupations – farmer, farm labourer, agricultural labourer, cowman, gamekeeper, thatcher and even mole trapper, rat catcher, and cutter are mentioned. One widow lady, Mrs Alice Pownell of Burtonwood Road, Bold rejoiced under the redoubtable description of mangle woman. At number 4 Chapel Lane, lived Joseph Moses, tailor whilst a mere 20 or 30 yards away lived Marcus Naylor of somewhat higher social standing being a master tailor. Few, if any, of these job descriptions would have been out of place in the 18th Century, nor would the fact that several people, notably widows, are referred to as paupers and Patrick Marren of Dallam and Betty Hughes, a 65 year-old widow lodging in Chapel Lane, are described as beggars.

But new factors in the Industrial Revolution were already beginning to appear in the village. William Ratcliffe of Hindleys Row, is described as a Flat Hauler on the Canal and in the former tiny hamlet of Collins Green lived several men employed in the glass industry, some in the Chemical industry, a few described as colliers and several more employed by the Railway company. The railway workers are particularly relevant for we must remember that prior to the 1830s and the development of a railway system, it was very rare for anyone to travel further than he could safely manage in a day. Consequently, people lived and died within a small radius and most of the village would be Burtonwood born and bred, staunch Lancashire men whose families had worked the land for generation upon generation, though the farmers often seemed to marry girls from outside the village.

It is therefore a great surprise to find that already by 1851, there were numerous outsiders who had already entered village life. William Aikin, the Police Officer, had been born in Cumberland and James Wood, a gamekeeper, was born in Southampton. It is perhaps understandable that a policeman and a gamekeeper should come from outside the village and be free from fear or favour, but Southampton seemed to be a little to far.

At the same time in 118 Joy Lane, lived James Aitkin and his young wife Margaret, both born in Scotland, at 17 Alder Lane lived James Layton, Shropshire-born and his wife Margaret who was born in the Isle of Man. Samuel Merrin, a master bricklayer came from Nottinghamshire whilst Jane Stead, a farmers wife of 57 Broad Lane, has the intriguing birthplace of Bognor, Sussex. Even by todays standards quite a distance for a Burtonwood farmer to do his courting! Nevertheless, pride of place for the birthplace of a resident was that of William G. Thomas, the Incumbent of the Chapel of Burtonwood, who was born in Barbados in the West Indies.

Yet by far the greatest proportion of the newcomers in 1851, were the Irish, escaping from the Potato Famine, and out of a population of 831 there appears to be 51 who were Irish born. There had always been a traditional small influx of Irish farm workers who would cross the Irish Sea in time for the English harvest to find work on the farms near to the ports only to return home after harvesting, but the Famine had changed all that. For many the journey would have been terribly difficult, possibly walking from their home village to Dublin, then by boat to Liverpool where, unable to afford the price of travel on the new railroads, many would set off walking inland. The Liverpool Mercury of April 1850 quoted one small group, consisting of Bridget Gallaghan, a widow of 40 years, her cousin and four young children, who landed at Liverpool in April 1850 and set off walking at once. They stopped the first night at Knotty Ash and reached Bold late the following afternoon where a local resident – allowed them to make some oatmeal porridge and also gave them some hot coffee. The poor woman and her family finally left at about 5 oclock in the evening and crept with her children under a hedge in the road. They remained there, although it rained heavily until 5 oclock the next morning, the children began to cry when a woman from the nearest house came to their assistance; the poor woman was carried to a straw stack and laid down, her limbs being quite stiff and she died a few minutes afterwards.

Those who did complete the journey safely tended to huddle together in what, in the big cities are now known as ghettoes, but in the small village of Burtonwood was known as Irish Row. Though the Census of 1851 shows that the occasional ones such as Mary Gibbons and Patrick Haverty lived and worked on the farms (in this case Causeway Farm and Farm ithi Fields respectively) it also shows that most congregated in a row of ten cottages, Hindleys Row, which became known as Irish Row, with some around the corner in Chapel Lane. On the night of March 30th 1851, there were 55 people, including 29 Irish born, resident in the ten terraced cottages of Irish Row, but it is a shock to find that all but one of the 29 Irish lived in just the two end cottages, number 9 contained 13 persons, 12 of whom were Irish born, whilst number 10 contained 15 persons, all Irish born. Twenty-eight people living in two simple agricultural cottages, most being described as lodgers! This overcrowding was symptomatic of the conditions in which most immigrants found themselves just off the boat. Hindleys Row was demolished around 1935 and is now replaced by Winsford Drive.

In 1851 the majority of these immigrants are described as agricultural workers with the occasional chemical worker although the aforementioned two beggars were both Irish born. It is however one of the more noticeable aspects of this Census that many of these Irish people seemed to have moved on, their names not being mentioned in later Censuses. There is a possibility that, being mostly agricultural workers, they continued to move with the seasons and the harvests, many being either single men or men without their families, or they could have joined the thousands who were deserting the land and flocking to the fast expanding industrial towns. Certainly it would appear that it was a later phase of Irish immigrants who became permanent residents of the village. By 1861 however, several new names appear and continue to reappear throughout the next century. At 59 Cow Lane, lived Michael and Anne Mulrey with their 12 year old nephew John Monaghan, whilst in Hindleys Row lived Thomas and Bridget OBryan and their two children, and John and Mary Mullany with their three. The overcrowded eased, for there were now two unoccupied houses in Irish Row, and by 1881 the names of many of the inhabitants of Hindleys Row have a very familiar ring to them.

The census of 1881 shows another distinct change in the village by its range of occupations. The traditional rural pursuits of farmer, farm bailiff (Ralph Cooper) and blacksmith still persisted, though not in such numbers as in 1851 when there were nine people described as blacksmiths resident in the village. But and abundance of new occupations appear – engine driver, plate layer, wagon maker, spring maker for wagons, boiler maker, iron driller, iron grinder, bolt maker, fitter and brick setter, the colliers and the chemical workers. There is no mention of just where they worked, but the Vulcan foundary and the railway works in Earlestown seem likely. Prior to 1875, when it was closed down because of its noxious emissions, the Bold Copper Company (Peasley Cross) would have employed some, and at sometime the chemical workers would probably have found employment at the Vitreol Works in Earlestown or New Keates Company of Sutton. Certainly the chemical industry, with its deplorable working conditions was a major employer of Irish labour.

Yet despite all of this Irish influence, Burtonwood was still dominated by the traditional village families. However, the same was not true of Collins Green where in 1881 it was difficult to find too many local born residents. Once a tiny hamlet, it was now situated on an important railway line with an expanding colliery offering company houses and so it was an ideal place to attract settlers. The residents therefore offer an amazing variety of birthplaces from Parr to Philadelphia. Indeed, the likes of Richard Naylor, the Burtonwood-born licensee of the Pear Tree Inn, were in a minority in this rapidly expanding hamlet.

Over at Bold Hall changes had also occurred. The vast estates of the Bold-Houghton family were sold in 1860 to one William Whitacre Tipping, a wealthy but eccentric Horwich mill owner, for ?120,000. Stories of Squire Tipping abound, some of them clearly mythical but all entertaining. When he bought the Hall the thousands of books in the Library were not included in the price and he was invited to make a bid for them – “I know nothing about books” he said, “but I do know something about muck and I will give a muck price for them”. The books including many masterpieces, were piled on a cart, weighed on a weighing machine and sold for 10/- a ton.

Once he had purchased the magnificent Hall, designed by the eminent Italian Leoni, Tipping closed many of the rooms. It became generally neglected and some of the finest old oaks in the kingdom were cut down and sold for timber. In 1876, he appeared before the Royal Commission on Noxious Vapours, giving evidence against the Bold Copper Company, claiming that their emissions harmed his cattle and destroyed vegetation, which resulted in the Copper Works being removed to Ravenhead.

Squire Tipping died in 1889 but such was his renowned eccentricity that even his funeral produced a probably apocryphal story. Every Friday his driver would take him to Wigan Market, stopping at the Pear Tree in Collins Green, for a drink, leaving the driver outside. On the day of the funeral, the self-same driver took the body from the Hall for internment at Horwich along the same route to Wigan. The usual stop was made at the Pear Tree, but this time the driver went in, “Every dog has his day”, he is supposed to have said to the landlord, Dick Naylor, “The old ***** left me outside for a good many years, now Ive left him there. And I bet he never wanted one half as badly as he does this morning”.

Coal

Early in the 17th Century, Richard Bold was warned for digging coals at Bold and thus endangering the local populace, so no doubt small coal diggings were not usual. Mossess Shaw of Parr who was buried at Burtonwood Chapel on October 29th 1697 was described in the parish register as collier kild in cold pit. Yet, well into the 19th Century commercial exploitation of some of the local coal seams still had not taken place. In 1839 an auction at the Legh Arms in Newton indicates that one coalfield at least was still mere supposition:

For Sale Valuable and Extensive Freehold Estates and Coal Mine…It is supposed that a valuable coalfield extends through the Burtonwood Estates.

Some fifty years later the Collins Green Colliery Company was producing 2,000 tons of coal per day at Collins Green. But as well as the coal there was also the problem of water in considerable quantities in the workings. Such was the size of the water problem that John Slee & Company of Earlestown built a pumping engine to raise it from 96 yards below ground to 20 yards above it, so that it might gravitate towards St Helens where it will supply a large proportion of the town with water of the purist quality. Numerous complaints from areas of St Helens suggest that the water was not as pure as it might have been.

The water, pure or not, nearly put an end to Bold Colliery. In 1875 the machinery for raising the water at Bold was overpowered and after the expenditure of some ?57,000 the undertaking was abandoned until 1878 when the Collins Green Colliery Company purchased the plant and sank another two shafts. The list of workable and potentially workable seams at Collins Green at this time will ring familar to generations of Lancashire miners: The Four Foot, Yard Seam, Higher and Lower Florida, Ravenhead High and Main, Roger Delph, Little Delph and Rushy Park.

The royalties of these two pits were owned by the executors of D Fairclough and others, from whom they were leased to the Collins Green Company under its chairman, Mr John Mercer of Alston Hall, Preston. The colliery manager was Mr Andrew Jackson. Also owned by the company was a brickworks in Burtonwood where a machine could turn out 10,000 bricks per day, many of which were used in the construction of 154 working mens cottages in the village. These cottages were arranged in three parallel terraced streets and named after one of the parsonages of the Company; Mercer Street, Fairclough Street and Jackson Street, all of which are still standing, though the Mercer Street Water Works, with a 24 feet high water tank over a well sunk into the New Red Sandstone, is now demolished. A social club and bowling green were also provided by the Company and in 1892 the club had 100 members. The Company claimed that it provided a means of recreation and gave interest and employment to the mind, but when Mr Anders of the Bridge Inn was applying for the second time for a full licence in 1898 for his beerhouse, he suggested that the Social Club was a place of drunkenness, but perhaps he was biased.

At the end of the 1920s, the Collins Green Colliery Club, which had existed “over the arch” that spanned the shops at the end of Mercer Street and Fairclough Street since the 1800s, closed down. A great storm had shattered the skylight, sending it crashing down onto the billiard table cracking the slate and soaking the premised. It never reopened after that and several of the younger parishioners, seeing the potential of the property, approached the parish priest, Father Roach, with an idea to use it as a parish club. At first the priest was opposed to the idea of it being a licensed club, but in 1932, it came to fruition with the full blessing of the then parish priest, Father Almond, under the name of Burtonwood Catholic Club. The premises were still owned by the colliery company and the rent of seven shillings a week was stopped out of the wages of the first chairman, Gerry Murray, at Bold Colliery.

The club was, and still is, an important centre for the social life of Burtonwood, but coal with which it was so closely linked, eventually brought about its downfall, in 1956 the arch was demolished due to mining subsidence and after a brief period in the chip shop next door, the club moved to new buildings, constructed with the help of Burtonwood Brewery, next to the site of the old grammar school, (which is now a youth club). Situated scarcely a quarter of a mile away across the fields from the Brewery, it can claim its beer could hardly be fresher! It has however, been called upon to cater to other needs, notably in 1972 when it served as a temporary Mass Centre after the demolition of the old tine church and in 1963 when it served as temporary classrooms during repairs to St Pauls School.

The link between Burtonwood and the coal mines was so strong that whenever there was a dispute in the pits it had a direct and immediate effect upon the village. Sometimes the results were startling as the local press reported on September 3rd 1883: A singular occurrence in connection with the Coal Strike is reported from Burtonwood. The Collins Green Colliery Company are erecting a number of cottages in that village and on Thursday, Thomas Prescott, farmer was taking a load of coals to brick kilns near the new houses when he was met by a gang of colliers who overturned his cart. A crowd of men, women and children, who quickly gathered, helped themselves to the whole of the coals, scarcely a vestige was visible when the police arrived on the scene. Special constables were on duty in the district yesterday to prevent a repetition of the occurrence . Again in 1911 during the Minimum Wage Strike extra police had to be drafted in to control the pickets at Collins Green.

The village was hardly a prosperous community even when the pits were working but at times of stoppages whole families suffered in those pre-Welfare State days. Yet, as in many mining communities, a real sense of solidarity, born of sharing common hardships seems to have existed. The 1926 strike was the time of soup kitchens, set up and funded by goodwill and such voluntary efforts as the several concerts which Jim Cunliffe and his Band played in the Church Hall for the Miners Soup Kitchen Fund. Unfortunately the difficult geological conditions and the water eventually made coal production uneconomical and Collins Green finally closed in the early 1930s. In the 1980s, Bold Colliery has gone the same way finally breaking the link between Burtonwood and Coal.

Beer

The water which was. and still is, such a drawback to local coal production was a blessing to the development of brewing in the area. In 1867 James and Jane Forshaw purchased the land upon which the present Burtonwood Brewery stands. It was an ideal position, between several fast expanding towns and with a plentiful supply of suitable water and thirsty colliers. James Forshaw has learned his trade at the Bath Springs Brewery, Ormskirk and then at Richardsons Brewery, Rainford. His early production at Burtonwood was on an understandably modest scale and a glance at the census suggests why: John Anders of 20 Alder Lane, Burtonwood, is described as a shoemaker and a beerseller, Peter Yates of Broad Lane as a beerseller and farmer of 3 acres and George Pownall of Broad Lane as a farmer of 22 acres, bricklayer and seller of beer.

James Forshaws first brewery at Burtonwood had a 14 barrel open-fire copper, two 12 barrel fermenting vessels and a cellar capacity for 45 barrels, producing mainly 4? gallon casks known as Tommy Thumpers. The water was drawn by means of the companys artesian wells. Early trade was with either Free Houses or the local farmers and landowners and it was not until 1874 that the Company purchased its first freehold public house. At that time the brewery was producing about 20 barrels per week, at 30/- per barrel, but within six years production had doubled.

After James death in 1880 the business was carried on by his widow Jane, and their nephew Richard, who in 1881 was described as the bookkeeper. In 1890 Jane was remarried to the vicar of Burtonwood, Rev. William Wilson, and Richard Forshaw, with the aid of a small legacy from his father, purchased the Company from her. Richard, or Owd Dick as he is still remembered in the village, soon proved himself to be an astute and far-sighted businessman. In 1895 Burtonwood became one of the first of the local breweries to produce bottled beers and they were an immediate success. Soon after the turn of the century he was quick to recognise the immense potential of the rapidly growing workingmens club trade and partly as a result of this the brewery was producing some 200 barrels per week by 1907. As trade expanded the Companys huge grey dray horse, named Kruger after the South African general, became a familiar sight in the streets of St Helens, Warrington and Runcorn and in 1912 the Company became one of the first to acquire a motor lorry: a Page Field Lorry, made in Wigan. Under Owd Dick the Company grew almost without a hitch.

The only hiccup in the steady growth of bottled beer occurred around the end of 1900 as a result of the arsenic scare or the Great Beer Crisis as contemporary newspapers dubbed it. Arsenic was found in considerable quantities in the beer of a Manchester brewer in November 1900. At an inquest on a woman who died from it, the Medical Officer of Health of Salford, put the blame on the suppliers of glucose or brewers sugar, used in the brewing process, revealing that pyrites had been used instead of pure sulphur in the making of sulphuric acid which in turn was used in the production of glucose: the pyrites had produced arsenic. All beer sales of all breweries understandably slumped and people in the trade held their breath, hoping that they had not been supplied with the poisonous brewers sugar. In December 1900 several people in Burtonwood village went down sick and on December 11th, John Rothwell aged 53 of Mercer Street, died from arsenic poisoning. Though the inquest held at the Chapel House merely confined itself to stating the cause of death without attributing it to any particular brewer, it was enough to send Forshaws beer sales plummeting:, only 99 barrels were sold in January 1901, scarcely 25 per week. It took several years before the brewing trade recovered from the Great Beer Crisis but by 1907, Burtonwood Brewery was again working at record production with 200 barrels per week.

These events did produce some interesting side effects for the Company was briefly put up for sale in 1903 only to be just as quickly withdrawn. The sale catalogue gives an accurate picture of the Companys assets at the turn of the century. Apart from the brewery itself, the Company owned just three beerhouses – the Coppersmiths Arms, Sutton, the Limerick Inn, Burtonwood and the Fiddle ith Bag, Burtonwood. Burtonwood leases were also held on the Bridge Inn, Peasley Cross, the Black Horse, Peasley Cross, the Elm Tree, Burtonwood, and the Bridge Inn, Burtonwood, together with some shops and property in Clock Face and Ashton, and several contracts with Free Houses. Today (1986) the company owns some 300 pubs.

It was at this time that Richard Forshaw, though not himself a Catholic, was said to have become a firm friend of Fr. Peter Morgan, the first parish priest of St Pauls. Owd Dick is remembered as being very kind to the poor parish of St Paul of the Cross in its early days, but he can scarcely have realised the extent of one of his acts of generosity, when a temporary church was built in 1902 Richard Forshaw promised Fr. Morgan that he would pay the annual insurance on the tin-and-timber building. He probably didnt realise at the time that the temporary structure would need insurance for some 70 years.

Heavily committed to his family business and equally involved in the community, Owd Dick was a typical Lancastrian self-made man. If his style seems patronising to modern eyes, he was no worse than many in his situation and probably better than most. He was a parish councillor, district councillor, county councillor, Poor Law Guardian, as well as a major employer in the village. The direct, no-frills style of his election address of 1910 could only come from such a man, )and perhaps can only be understood fully if read with a true Lancashire accent).

Guardian of the Poor – there has not been a case of outdoor relief that has not received due and proper attention. I go personally into each case that comes to my notice.

Parish Council – I am very proud of the share I had in the institution of the cemetery. With regard to the treatment of my sewage I am laying down a system of filtration…etc., etc., etc.

In gratitude for the sage return of his sons Richard and James from the First World War, he instituted the Forshaw Trust to fund an annual treat for the children of the village, a trust fund re-discovered after being forgotten for some years.

During and after the Great War, Richard and his eldest son, Tom, continued to expand the business in Lancashire and Cheshire whilst his younger son, Richard Dutton-Forshaw, founded the Burtonwood Engineering Company in 1922. After Owd Dicks death in 1930, Tom Forshaw took over the helm, seeing tremendous opportunities for growth in North Wales. The first house he bought was the Dudley Arms at Rhyl and this was followed by over 100 other houses in the North Wales/Anglesey area. The brewery was renamed Burtonwood Brewery Co. (Forshaws) Limited in 1949 after a reorganisation of family holdings and went public in 1964.

Despite its increase in size, there are presently over 300 pubs throughout Lancashire, Cheshire, Staffordshire and North Wales, the Company had assiduously maintained its local tradition and strong village links. Tom Forshaw who steered the Company into the modern age of brewing was also a student of local history and a keen antiquarian. He would have been proud of the fact that the Company has sponsored the Rugby League Lancashire Cup, even though it is now in Cheshire.

Education

In 1867 Burtonwood had a grammar school at the corner of what is now Phipps Lane and Clay Lane. In 1601, Thomas Derbyshire had left ?40 for a minister and schoolmaster and, four years later, Thomas Bold gave the land upon which an Anglican chapel and schoolhouse might be built. In 1741, Peter Bold directed that a section of the town carriage house, in which the public carriage of the inhabitants of Burtonwood was kept, be set apart and used as the school and in 1793 Joseph Lucas left ?40 in his will for a Grammar School.

The very poorest class, including the Irish settlers, did not go there. In Hindleys Row a school conducted by John Mullaney an Irish agricultural labourer and his wife.

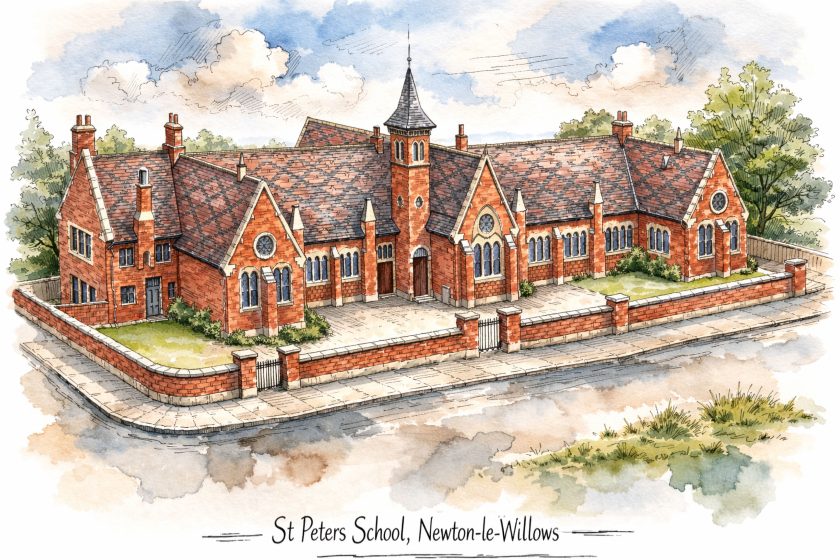

St Pauls Roman Catholic School was opened on January 24th 1887, with a staff of one certificated teacher and two pupil teachers, and a compliment of 30 boys and 20 girls.