THE FEE OF MAKERFIELD ; WITH AN ACCOUNT

OF SOME OF ITS LORDS, THE BARONS

OF NEWTON.

By William Beamont, Esq.

(READ FEBRUARY 22ND, 1872.)

ENGLISH historians have joined chorus in ascribing to our immortal Alfred the institution of hundreds and townships into which the country is now divided. Certain it is that when he resumed the throne after his temporary retirement, and found, owing to Danish misrule, the ancient police of the country in ruin, he first set himself to readjust and settle upon their present basis the shires of the kingdom, and then divided them into hundreds, and these again into vills, town-ships, or decennaries. But fas est ab hoste doceri, and from Denmark where hundreds, each under its own centenarius, had been known both as a civil and military division of the country for two hundred years, Alfred probably introduced that institution into England, although something similar to it had prevailed among the ancient Germans, from whom both the Franks who became masters of Gaul, and the Saxons who settled in England, were derived.

In England, however, and particularly in the northern counties, it seems not to have been always necessary that a hundred should contain a hundred townships, for where a large district happened to belong to one owner, such a district, without reference to the number of its vills, was often constituted a hundred. Gayton in Cheshire, and Newton and Warrington in Lancashire, became hundreds of this sort. (His. Chesh. ii, 275-285, and the Domesday Survey of South Lancashire.)

Alfreds great achievement, of which he is entitled to the full merit, was his dividing the kingdom into tithings, decen?naries, vills or townships, each containing ten families, and in each of which?an excellent way to preserve the peace every man was made answerable for his neighbour, while in each there was a domestic tribunal where justice was administered to every man at his own door. Parishes which existed at this time as an ecclesiastical division were not the same as tithings, nor were their boundaries necessarily coincident with them. Of the vills or tithings of which I am to treat, a former seneschal of the district, who had the gift of song, in describing how they answered the call of the great Alfred to meet him with their forces in the field, has given us a sort of catalogue in verse

On champing steeds,

Speed generous hearts, select where Winwicks brow

Uplifts the stately spire, and draws the feet

To sainted Oswalds pilgrim haunted well.

Stalwart champions under banners bright,

Led by a haughty warrior, rush from the marge

Of Newtons willowed stream, and ample range

Of Macrefield, boasting its spread domain ;

Whose garrison with battle-axes armed,

Its oak-crownd fortress, and the barrow old,

Quit reard majestic oer its sunken dell.

With these in friendly league come sinewy troops,

(Each in his grasp unscabbarded a brand,)

The flower of Golbornes Park and winding dale.

Impatient of restraint, on fire for fame,

Combine throngd bands from Haydocks ample plain,

Or in coruscant armour sweep along,

Chivalry bred in Garswoods beauteous home,

Or emulous of equal fame, aspire

The valiant band, nursed where Bryns swelling brow,

Protects its race, for prowess old renownd.

Ready alike, Winstanleys generous line

Spreads from its lawns and closures fertile fresh.

While drawn from neighbourd tracts adventurous rush

Comrades select oer Culcheths heathy range ;

Colleagued with whom the gallant veterans spring,

Impetuous sped, from Hindleys mansion site ;

Or onward gathered till the Douglas stream

Laves scenes yet sounding British Arthurs fame,

Where Wigan rears its burgh and busied homes,

Intent alike on triumph and to chase

Plunder and Pagan fury from the land.

(Alfred, by J. Fitchett, B. 44.)

Before we pass on, some of these places call for a few remarks ; and first of these is Winwick. This place, like many others in South Lancashire, has its parish church placed at its southern end, as if to show the quarter from which the wave of population had first reached it. The learned Usher was of opinion that it was the Caer Gwentwic of Nennius, and had thence derived its name ; and De Caumont gives us a castle in France called Vineck, a name which sounded by a French tongue would seem very like Winwick. But we need not go far to seek for an etymology of the name since it plainly is derived from the two Saxon words win wick, the place of victory.

On the first planting of the Northumbrian kingdom we might expect to find a fortress placed on its southern boun?dary, and such a fortress, with the kings palace near it, there was probably on the Mersey at Warrington.

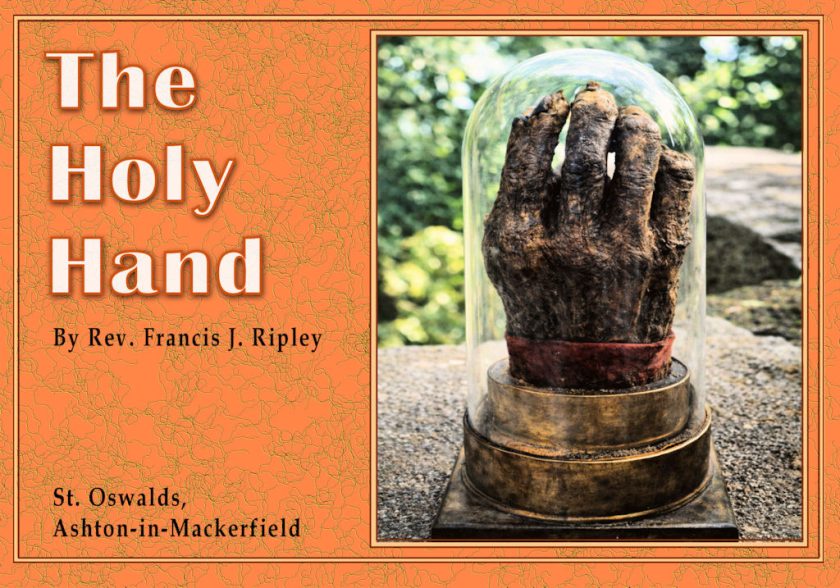

The frequent inroads of their Mercian neighbours, however, caused the removal of the palace to Winwick, when the defence of the frontier was left to the garrison at Warrington, where king Oswald, the first of the Northumbrians to intro-duce Christianity into his dominions, had placed St. Elfin, probably one of the Icolmkill priests, whose name the Domesday Survey preserves to us, to instruct his people in the new faith. We are fortunate in knowing Oswalds history, and the date when he suffered martyrdom and was raised to saintship, which by inference gives us the date of an early Lancashire parish. The king, who had passed his early life in exile, and had so used his time as to improve his great natural parts by study, was called home by the defeat and death of his uncle in battle in the year 638, when, mustering some forces, he encountered and defeated his enemies near Hexham, and slew their leader. He began his reign by establishing good laws, and teaching his people religion and submission to rule. Often when Aidan, one of his priests, was preaching to them Oswald might be seen acting as his interpreter, while such was his compassion to the poor that he often sent them food from his own table, which so won upon the good opinion of the people that they called him " The Bounteous Hand." But his envious and ambitious neighbour, Penda, soon found occasion to quarrel with him, and, having invaded his territories, surprised and slew him near Winwick on the 5th August, 642, which Spenser, assuming to be both a seer and a poet, foretells when he says:-

His foe shall a huge host into Northumber lead,

With which he godly Oswald shall subdue,

And crown with martyrdom his sacred head.

Near the place where he fell there is a well, which bears his name, and near the church there is one of those ancient wheel crosses called after Paulinus ; but his most remarkable memorial is the church itself, which is dedicated to him, and round the cornice of which runs this monkish legend :-

Hic locus Oswalde quondam placuit tibi valde

Nortanhunbrorum fueras rex, nunque polorum

Regna tenes prate passus Marcelde vocato

Poscimus hinc a te nostri memor esto Beate.

(A line over the porch obliterated.)

Anno milleno quingenoque triceno

Sclater post Christum murum renovaverat istum

Henricus Johnson curatus erat simul hic tunc.

This place of yore did Oswald greatly love,

Northumbrias king, but now a saint above,

Who in Marceldes field did fighting fall.

Hear us, oh, blest one, when here to thee we call.

In fifteen hundred and just three times ten

Sclater restored and built this wall again,

And Henry Johnson here was curate then.

The pious prayer, " Requiescat in pace," inscribed in old times over the grave of a saint, was but a piece of mockery, for the saint was but seldom allowed to rest in peace. King Oswalds fate was indeed especially hard, for he was buried piecemeal. His head and right arm, which at first were buried at Lindisfarne, were afterwards translated thence, and while his head was buried in St. Cuthberts grave at Durham, his right arm was removed to Bamborough, where it was enclosed in a silver shrine. His left arm was in the possession of Wulstan, at Worcester, to which place also his body, which was first buried at Bardney, was afterwards removed. It is a sign of the high estimation in which the saint was held that a second head was found for him, which was enclosed in a niello shrine, and held in great reverence at Hildesheim, while a third arm, celebrated for its healing powers, was found for him at Peterborough, and one of his bones was kept at York as among the most valued treasures of its minster.

If, as tradition asserts, king Oswald had a palace at Win-wick, it was neither a stately nor a substantial structure. No wonder, therefore, that no traces of it remain. It was probably built only of wood and wattles, surrounded by a moat, much after the fashion of the house of Cedric of Rotherwood, as it is described in Ivanhoe.

* The Winwick Terrier of 1701, states that there were these five lordships in this township?Culcheth, Risley, Holcroft, Pesfurlong, and Chateris, which last may mean Charterers.

Culcheth,* another of the townships mentioned by our local bard, puts in a claim to be that Celchyth in North?umbria, where the three councils of 786, 801, and 816 were held, at the first of which Offa crowned his son, raised Lichfield to the rank of an archbishopric, and procured a decree establishing the six general councils ; at the second Lichfield was reduced to its original rank, and at the third there were made various canons, and in particular that useful one that bishops should visit their dioceses at least once a year, " Utpote Mi audiunt qui raro audiunt verbum Dei." King Offa presided at the first two councils. Jaenbert was archbishop at the first, Ethelhard at the second, and Wulfrid at the third. (See Thorpes Diplomatar. Anglic., 38, 45, and 72.)

Archbishop Parker was of opinion that these councils were held in Northumbria, and both Sir Peter Leycester, a very careful investigator of our local antiquities, and Dr. Hook, think that Culcheth in Winwick was their place of meeting. (See P. Leycesters Hist. Chesh., i, 134, and Hooks Lives of the Archbishops, i, 250 n., 265, 279.)* If Kenion, which adjoins Culcheth, really means, as it is said, the place of tents, and Kinknall-within-Culcheth, means the kings dwelling, both may be memorials of these councils. (Whitakers Hist. of Manchester.)+

* But this is controverted in a late work, where it is said Cealchythe was identified with Culcheth in Lancashire, by Gibson (Anglo-Sax. Chron. p. 93), following Archbishop Parker (Antiq. p. 93). Spelman preferred a Mercian site, in which he is undoubtedly right. Alford (Annales ii, 647), first pointed out Chelsea as the probable place, and on comparison of the charters where it occurs, there seems no reasonable doubt that it is right. Newcourt (Repertorium i, 583,) gives as the old forms of the name Chelsea?Chelcheth, Chelchyheth, Chelchyth, Chelchith; the form Chelsey appearing first in 1554. The form in the taxation of Pope Nicholas is Chelcheth. Any site near London, which was regarded locally as in Mercia, would be a good place of meeting for the West Saxon, Kentish, and Mercian bishops.?Haddan and Stubbs Councils, 1872, p. 445, in notis.

+ The editor of Mamecestre (Chet. So., 564,) asks whether Chat Moss is indebted for its name to St. Chad, who was bishop of Lichfield in 667, and was afterwards translated to York.

Newton, another vill in the bards poetic catalogue, which occupies a site intermediate between Winwick and Wigan, may have owed its origin to some calamity which befel one or both of those frontier towns, and we need be in no doubt as to the meaning of its English name.

As to Wigan, the northern frontier of the district, it was affirmed, says Camden, that it was formerly called Wibiggin, and that he had nothing to say of its name save that in Lancashire they called a building a " biggin." (Britannia, 790.) But the Anglo-Saxon word " wiggan," to fight or contend, offers a more probable origin of the name, and this it may have obtained from the old fights which are known to have taken place there. Near those shores from which our Saxon ancestors came there is still a place of the same name, which is made the subject of an allusion in Ochlenschlagers play of " Palantoke."

Harold asks

Wer machte zum Statthalter dich in Wigen ?

and Schwend replies

Du sandest mich nach Wigen and nach Schonen.

Who made thee chief in Wigen?

Twas thou didst send me forth to Wigen and to Schonen.

About the year 516, when the chivalrous Arthur was struggling to re-establish British supremacy, several battles occurred on the banks of the Douglas, which have been alluded to not only by our local bard but by the present Laureate —

And Lancelot spoke,

And answered him at full as having been

With Arthur in the fight, which all day long

Rang by the white mouth of the violent Glem,

And in the four wild battles by the shore Of Duglas.

(Tennysons Idylls, p. 162.)

Tradition makes Wigan to have been the scene of these battles, and repeated discoveries of remains strongly confirm the tradition. Until the year 1770, there existed at Wigan a considerable British barrow, called the Hasty Knoll, which was composed of small stones taken out of the bed of the Douglas, and which probably marked the site of these battles. In the knoll there were found numerous fragments of iron, various military weapons, such as our ancestors buried in the graves of their heroes, and under all a cavity seven feet in length, filled with black earth and the decomposed remains of one of the fallen chieftains. (Whitakers Hist. Man., Saxon Period ii.)

The custom of heaping such memorials over those who have fallen in battle has prevailed from the earliest times, and the native bard whom we have already mentioned thus refers to it

Others with toil collect

Hugh stones and earthly portions, whence to raise

The hilly mounds, which oer their comrades dear

Heapd numerous may display to future times

The field of former slaughter. Thus while round,

Soft in their earthy beds, the living lay

The warriors fallen, and by their side dispose,

As wont, the spear and shield, the solemn priests,

In flowing garments habited pass slow,

On every hand invoking heavenly grace !

(Fitchetts Alfred, i, 55.)

From the Domesday Survey we learn, that in Neweton hundred there were in king Edwards time, V hides, of these I was in the demesne. The church of the same manor had I carucate of land, and Saint " Oswold " of the same vill had II carucates of land, free of every thing. The other land of this manor, XV men called drenghes, held for XV manors, which were berewicks of this manor, and among them all these men rendered xxx shillings.

Now the Newton hundred, which is here described, and which comprised the two parishes of Winwick and Wigan, in which there were much fewer than a hundred vills, is with a trifling exception identical with the fee of which we are to treat. By succession from King Oswald the Martyr, Edward the Confessor was its head, and all the land of its fifteen subordinate manors or berewicks, was held under him by an equal number of drenghes. Berewicks, which in the Domesday Survey occur only in our northern counties and in Flintshire, but are mentioned in many Saxon charters referred to in Ducange, and also in the Sharnburn charter, though its genuineness is suspected, were hamlets within a manor which possibly obtained their distinctive name from the crops of that poor grain called here, which were raised in them.

But Ducange, who seems not to agree with this etymology of the name, prefers to derive it from the Saxon berier vil, that is, vicus manerii, but the northern berewicks being held by persons who were to render husbandry services, rather supports the idea of their name being taken from the growth of grain. The drenghes are supposed to derive their name either from thingus, a low Latin word for a thane, or from the Anglo-Saxon, dreogan, the original of our word to drudge, and hence the boy who attends to the cabin in a Norwegian vessel is called at this day the cabin-drengh. According to Spelman (Glossary 186, edit. 1664) the drenghes were military vassals, who or whose ancestors had held their patrimony before the Conquest, but the better opinion now is, that the drengh was the lowest landowner who had a permanent interest in the soil, and that his position was midway between the freeman and the villein. In some respects his services were the same as the villeins, but though he rendered boons and plowed, sowed and harrowed the lords lands like him, he rendered these services, not personally, but by the villeins under him, he and his household being exempt. His tenure was inferior to knights service, or free tenure, but from its being a perma?nent tenure, and from his being personally exempt from servile work, it was superior to villenage, and this view of it is confirmed by a recently discovered charter, by which a drengage holding is converted into a tenure by knights service, and by the letter which Bishop Flambard addressed to all his thanes and drenghes, which seems to shew that a drengh who held more manors than one was called a thane. (Boldon Book, by Surtees So., Append. xliii.)

The Newton hundred contained two parish churches, which though not named are sufficiently referred to in the Domesday Survey. Thus it is said " the church of the same manor had " one carucate, and Saint Oswald of the same vill had two " carucates free of everything." It is certain that the church with its one carucate was at Wigan, and that Saint Oswalds with its two carucates was at Winwick. Wigan was a favoured church, but Winwick was still more highly favoured. It had double the endowment of either Walton or Warrington, and it enjoyed the rare privilege of being exempt from all taxes, even the Dane gelt, which was shared by no other church in Lancashire, except Whalley.

A number of woods, which covered, when they were added together, an area of sixty square miles, were scattered over the district, in which beside their other wild inhabitants, there were aeries of hawks kept for falconry, not then as now a mere amusement, but almost a necessity of the time. Except two, all the free men of the hundred (a significant term, shewing that some of our ancestors were serfs or bondmen) were liable to the same custom as the men of West Derby, except that, which was perhaps either because their land was better, or because part of the hundred was exempt from all taxes, they did two more days work for the king in time of harvest, which seems then to have happened in August as it does now. The two exempted free men were privileged persons, had the weregild or forfeiture for rape and bloodshed, and had also the right of free feeding for their hogs in the lords woods. The farm rent paid to the king for the whole hundred was only ten pounds ten shillings.

What was the meaning of some of the terms, and what the exact extent of many of the measures used in the Domesday Survey, we do not know with certainty, but clearly the hide, one of the most frequent of them, did not mean that classic quantity used to define the bounds of Romes ancient rival, Carthage

Quantum taurino possint circumdare tergo.

As much ground

As with an oxs hide they might surround.

Many of the Domesday measures are thought to have been a sort of compromise Between superficial extent and productive value, but in these northern parts the hide seems to have contained six carucates of eight bovates, each of which contained sixteen acres, so that a whole carucate consisted of 128, or rather more than six score acres, the favourite number or tale by which, as the proverb runs, our ancestors were fond of reckoning most articles ?

Five score of men, money, and pins,

Six score of all other things.

If it be true then that the hide denoted ploughable land, and the carucate that actually ploughed, there were 3,840 acres of the former, and including the church land, 1,626 acres of the latter in the hundred or manor of Newton at the time of the survey, from which it would seem that of the whole hundred, now ascertained to contain about 53,581 acres, there was, after deducting 38,400 acres of wood, a tenth part of the whole, then capable of being ploughed.

From the evidence we have of the condition of the Fee of Makerfield in Saxon times, it is clear that the plough, though a more necessary, was then not so honourable an implement as the sword. In those ages men could not, nay even dared not walk alone, and as a consequence people generally, and all the inhabitants of cities and boroughs in particular, ranged themselves under the banner of some powerful per?sonage, and lived beneath the shade of his castle in guilds or fraternities, the more safely and securely to carry on the several callings in which they were engaged. In the hundred of Newton we may safely conclude that there were at least the three towns of Newton, Winwick, and Wigan, in which the trading community were thus banded and collected together.

The Hundred of Newton having thus resolved itself into the Fee of Makerfield, you have a right to ask for a definition of the term fee. The word fee, then, has various meanings. It sometimes signifies the vales expected by the domestics from the visitors of a great house, where it is of the nature of a gift, a sort of English backsheish ; something morally, but not legally due. At other times it may mean the reward to the servants at an hotel, which from a bad custom has grown to be an established right. Again, it may be applied to the regulated and established payments made by their clients and patients to members of the two learned professions of law and physic, whose palms are said to have a peculiar muscle for weighing and appreciating fees called the musculus guinearum, or guinea muscle. Or, lastly, it may signify the most exten?sive interest known to the law which any man can have in lands in England, and which a poet, better acquainted with Themis than the Muses, thus describes in verse :

Tenant in fee —

Simple is he

Who needs neither quake nor quiver,

For he holds his lands,

Without fetter or bands,

To him and his heirs for ever.

None of these senses of the word, however, will meet the use I intend to make of it, and we shall find it a meaning distinct and different from each and all of these.

When the custom prevailed, as it did all over Europe in feudal times, and more especially in England after the Norman Conquest, of rewarding all who had assisted to conquer a country with a gift of part of the lands they had conquered, the gift was called a feud benefice, or fee ; and every such gift by its very terms involved the mutual relations of protec?tion in the giver and service in the receiver.*

* It did not always happen that a gift without the former owners consent, was so happily thwarted as in the case of that spirited Saxon, Leighton, after-wards Bulstrode, whose story has been turned into the following ballad :

Ill fared our sires when bowd the land

Beneath the Norman sway,

And none of conquring Williams band

Unguerdond went away !

Thus spake he to the bold Fitzurse:

" The Leighton lands are mine ;

Thine they shall be?let none reverse

This gift to thee and thine

Instant on bended knee, the knight

His ready homage paid,

And straight to seize his new falln right,

His men at arms arrayd!

To Leighton swift the foemen came,

In hopes, ere dawn of day,

By night, as felons seize their game,

The Leighton lands might they.

If the feudal gift were large the receiver in his turn granted out portions of it to his followers, to be held from him on the like terms as he held the whole from his superior. All such gifts were originally called fees. The larger of them (which, owing military service, are called knights fees) generally embraced several dependent manors, all held of it, all dependent upon it, and all owing it suit and service. Such a paramount manor was that of Newton, called in the Domesday Survey the hundred of Newton, and which is now called THE FEE OF MAKERFIELD, a territory of great extent, comprising within its limits no less than these nineteen townships :

1 Newton 4 Golborne

2 Wigan* 5 Haydock +

3 Lowton 6 Ince

The news by Ulric, Leightons thane,

Was heard without dismay;

" Heaven will," he said "the right maintain,

Be robbers.who they may.

"So bar the gates, the drawbridge rear ;"

And on the highest tower

Uprose his banner, with a cheer

From all the Leighton power.

Now hark, a summons loud and shrill

Those castle warriors calls,

To yield it to Fitzurses will,

And own themselves his thralls.

Swiftly from Saxon mangonel

And bowstring came a hail,

Scattering the foemen where it fell,

And making bold hearts quail.

Soarcehushd the noise,when from the king "

A herald calls, " Forbear !

Ulric, to thee command I bring,

That thou to court repair."

" I go," the thane replied; " bring me

From out my herd the bull;

Thus mounted, I will hear and see

The kings behests at full."

Now Whang, the bull, had sides like snow,

Which, pure in realms of light,

Takes, as it falls to earth below,

Stains on its spotless white.

On steed so strange, with dauntless brow,

Ulric to court repairs;

There sees the king, and homeward now

This royal mandate bears!

" Fitzurse shall other guerdon have,

Than brave mens lands like thine;

Take back thine own, this all I crave

Fealty for me and mine!

Go," said the king, " for Ito thee

Thy Saxon lands restore ;

Thy name henceforth shall Bulstrode be,

And Leighton be no more.

* The Bailiffs of Wigan regularly paid 6s. 8d. at every Newton Court until the act passed for the " Reform of Municipal Corporations Act."

+ Hugh de Eydok held this place as a mesne manor of Newton, temp. Hen. III, and in 18 Ed. II, Gilbert de Haydoc had license to impark the place, and to have free warren in Bradley.

In the narrative De Celebratione Missae this story is told?A gentleman of Haydoc had a concubine who died. After her death he married, and going one day by the cross at Newton, her spirit appeared to him and entreated him to procure masses for her soul, that she might be released from the punishment she was suffering. She begged him to put his hand to her head. He did so, and took thence half a handful of black hair, upon which she entreated him to have a mass said for every hair, and promised to meet him afterwards and declare the result. She met him afterwards and exclaimed joyfully, " 0 benedictus sis inter homines qui liberasti nae de maxima paena, &c."?MSS. Trin. Coll., Oxford, 3, 13. A work by Richard Puttes.

7 Pemberton

8 The two Billinges, formerly one town-ship

9 Winstanley

10 Orrell

11 Hindley*

12 Abram

13 Kenyon

14 Ashton

15 Southworth-with-Croft

16 Middleton and Arbury

17 Woolston-with-Martins‑

croft

18 Poulton-with-Fearnhead

19 Winwick-with-Hulme.

* Rob. de Hindley fourth son of Hugh de Hindley had a grant from Rob. Banastre, temp. Ed. I.

All these townships being within the fee, and, except Winwick, all of them owe suit and service at its courts, and during the continuance of the feudal tenures, which were only abolished at the Restoration, yielded the lord a fruitful harvest in the shape of reliefs, wardships, marriages, heriots, and other services. Winwick, which, as we have seen, had been very early erected into a parish, had, pro?bably before the Conquest, passed into the hands of some religious house, although no traces of such a connection appeared in the presentations of the early rectors. But at Nostell, in Yorkshire, Ilbert de Lacy, in the time of William Rufus, in honour of St. Oswald, endowed a priory of canons regular, of the order of St. Augustine. (Tanners Notitia, 645.) On this priory Roger of Poictou, who was patron of the church, bestowed the living of Winwick, which gift Stephen, Earl of Moreton, before he became king, afterwards confirmed. (Testa de Nev., Dugdales Monast., iii, 92.) If our conjecture that Winwick was in the hands of the religious before the Conquest be correct, then both Rogers grant and Stephens were only confirmations of some still earlier gift. In consequence of this gift, however, Winwick, though within the limits of the Fee of Makerfield, is not called over at its court, and what marks its independence more distinctly, the rector holds a separate court of his own.

Going back for a few minutes to the year of the Domesday Survey, 1086, and ascending Billinge or Ashurst Hill, if we feast our eyes over the wide borders of the Fee of Makerfield, we shall see, instead of a cultivated country divided by numerous enclosures, smiling like a garden, teeming with population, and accessible on all sides by roads, canals, and railways, and busy in the pursuit of arts, commerce, and manufactures, a great sea of wood, tenanted by wild animals, some of them of races now nearly extinct, divided here and there by large commons of moor, heath, and waste, with an occasional piece of water or mere, about which are thinly scattered the mud cabins of its one hundred and fifty inhabi?tants, in the midst of their small green patches of cultivation, which look like islets in a dreary waste, and at the two extremities of the district, their towers pointing heavenward, are the two churches of Wigan and Winwick, then probably humble structures of wood.

If from the place we turn our attention to the people, we shall see, perhaps, two or three franklins or yeomen, each in his short green kirtle, with hose of the same colour, a leathern cap, a short sword, a horn slung over his shoulder, a long bow in his hand, and in his belt a bundle of arrows. In another direction a serf of one of the two privileged franklins is driving his masters swine to feed upon the mast and acorns of the neighbourhood. He has a staff in his hand ; his dress is a long jacket made of the skin of some four-footed animal, tanned with the hair on. It has been put on over his head, like a frock, and is buckled round his waist with a girdle. He has sandals, and not shoes, upon his feet. On one side hangs his gypsiere pouch or scrip, and on the other a rams horn, with which from time to time he issues his commands to his attendant hound and collects his herd of grunters when they wander or miss the pasture. The evening sun is casting slant beams on Winwick tower, and across the velvet turf of its adjoining demesne, at the call of its single bell, a shaven priest is hastening to perform the office of vespers.

After the foregoing account of the Fee of Makerfield, we pass on to give some account of its lords, the Barons of Newton.

If Dr. Hume is right in deriving the name of Makerfield from the British words " maes " and " hir," a field and a plain, the name would seem to be formed on the same model as that of Tor-pen-how-hill, each syllable of which means the same thing. In the Conquerors general distribution of lands among his soldiers and followers at the Conquest, this portion of South Lancashire fell to the lot of Roger of Poictou. The Banastres had followed the Conqueror, and while Robert, who was one of them, occurs in the celebrated roll of Battle Abbey, Richard, who was probably his son, was witness to a charter of Hugh Lupus, Earl of Chester, as well as to another charter of Randle I, the earls nephew. (Hist. Chesh. i, 12, 19.) Robert, who is said to have helped Roger of Poictou to win his possessions, received from him as his share of the spolia opima, the fee of Makerfield. From Hugh Lupus most probably he also received Prestatyn in North Wales. As to the origin of the Banastre name the suggestions have been various. Camden, in his remains, expresses an opinion that it was a corruption from balneator, master or filler of the bath, and just as the architectural term baluster has come to be called indifferently a baluster or a banister, so the great antiquary probably thought the Banastre name, wanting the prefix of " del," was derived rather from the Latin than the French. But Ducange gives us the words banaste, banastre, and benate, as the French names for a basket or creel, and there are persons, and amongst them their excellent descendant, the author of the family pedigree (Arch. Cam?brensis iii), who think that as the good Lancashire name of Bushel came from no nobler word than the low Latin busellus, a bushel, so the Banastres derive theirs also from banastre. The early cognizance of the Banastres, a pair of what may either be leather buckets, water bags, or creels, does not settle the point either way, and though we should prefer balneator as the more honourable, the evidence rather inclines us to think the creel is more likely to have given origin to the name.

If Robert Banastre, who was sometimes called Robert de Waleton, did any great actions, they are hidden in oblivion, as he lived in an age that had few chroniclers, and we may well imagine that in defending himself and his possessions against their former owners, he found abundant occupation. He was probably succeeded by his son Richard, of whom history tells us no more than that he appeared as witness on the two occasions we have already mentioned. To him suc?ceeded a second Robert Banastre, who, fancying himself more settled in his possessions, built a castle upon his demesne of Prestatyn ; but he, however, had counted too soon upon peace and security, for about the year 1167, the Welsh chieftain, Owen Gwynedd, having attacked him and taken his castle, Robert, after a vain attempt to maintain his ground, withdrew with all his people into Lancashire, where their wholesale immigration obtained for them the name of Les Westrois or Westerns, a name which they retained for more than a century. This Robert was lord of the Fee of Makerfield, which gave to his descendants the feudal title of Baron of Newton. He had also a grant, or more probably a confirmation, from the first Henry de Lacy of the lordship of Walton le Dale, with its members pro servitio unius militis, and about the year 1147 we find him a benefactor to Basingwerk Abbey. We do not know whom Robert married, but we know that he left three sons, Richard, the eldest, who dying without issue before the year 1204, was succeeded by his brother Warin, who married a wife named Sara, and dying without issue was succeeded, in 16 John, (1213,) by Thurstan, his youngest brother, whose wifes name was Cecilia. It is remarkable how slowly the names of the wives of our ancestors emerge into light in old times. At first they are quite anonymous, then their christian names simply appear, after which we have both their christian and surnames, and at length we learn both who and what they were. The law was at that time very unsettled, " might often " made right," and then if ever, as Thurstan found, possession really did make nine parts of the law, for when he came to his estate, the king exacted from him 500 marks for granting him an inquest of office to ascertain whether he was entitled to the lands of Robert his father and Warin his brother. Warin sealed his charters with the family badge or cognizance of two creels, buckets, or skin-bags enclosed in an external network to strengthen them.

Before the time of Thurstan and Cecilia the great Banastre inheritance had passed for two generations through collaterals. But Thurstan and Cecilia had now two sons, of whom Robert, the eldest, who married Clementia, succeeded to the barony, and Thurstan, who married Maria Vernon, to whom his brother gave lands at Newton in Wirrall, and from whom sprang the Banastres of Bank and Brotherton. This line had for their arms?argent, a cross patonce, sable.

Robert Fitz Thurstan Banastre, being only a year old in 1219, when his father died, his wardship and marriage de?volved upon the king, who sold both for 500 marks, a sum which shows the great value of the property, to Philip de Orreby, justice of Chester, who married him to his daughter Clementia. Henceforward the Banastres bore a coat of gules, three chevronels argent, evidently derived from that of Orreby, with a change of tincture, which was a common practice on the adoption of the arms of an heiress. On their seal they used their old badge of creels or water buckets on either side of the shield-like supporters. His early death, which might have been hastened by the troubles of those times, happened before the 27th July, 1242. By his wife, who survived him, he had issue John, who died an infant before 16 Henry III, (1241,) and Robert, who survived him. It was either by Robert Fitz Thurstan as Baron of Newton, or his son, that Sir John Mansel was presented to the rectory of Wigan.

Sir John, who was of the house of Margam, in Caermar?thenshire, being the son of Sir Henry Mansel, was unusually well educated for that time. Beginning life as a layman and a soldier, it was not until he had become the parent of three children and lost a first wife and probably a second that his grief or his ambition led him to take orders. As an ecclesi?astic he became the trusted and faithful councillor of Henry III. He was a successful ambassador to France, the Pope, Scotland, and Spain, and from the latter he brought back the celebrated treaty with Alphonso of Castile, by which he renounced to the King of England all claim to Gascony, and which, with its golden seal, is still preserved among the public records of the kingdom. When in Scotland in 1248, he was detached by the ambassadors from England to lead an armed band against Norham. In 1254 he was appointed proxy to wed the Princess Eleanor, and upon the actual presence of the bridegroom being insisted upon he accompanied the queen and Prince Edward to Burgos, and was present at the marriage. He was chaplain to the Pope and to Henry III, provost of Beverley, treasurer of York, and chancellor of St. Pauls. He held a deanery and stalls in several cathedrals, and upwards of 300 ordinary benefices, the wealth of which, said to amount to 18,000 marks a year, enabled him to entertain the kings and queens of England and Scotland, Prince Edward, and the nobles and prelates of the court at his house in Tothill fields. His covetousness, and still more his devotion to Henry III, drew upon him the displeasure of Simon de Mont-fort, and brought about his exile and ruin ; but Henry, who always stood his friend, described him " as educated under " our wing, whose ability, morals, and merits we have approved " from our youth up," a testimony confirmed by his appoint?ment as one of the executors of his will in 1252. He died beyond the sea, " in paupertate et dolore rnaximo," in 1268. (Archaeologia Cambrensis, 3 series, xxxviii, 108.)

Robert Fitz Robert Banastre, Baron of Newton, in 26 Henry III, (1242,) was in ward to the prior of Penwortham. but in the account of that priory John, and not Robert, is men?tioned as the wards name, (Chet. Soc. pref. xxxii) ; probably the elder brother had died in infancy, and then Robert became the ward. These repeated wardships must have sadly impover?ished the Banastre estate, and we wonder that they did not wholly consume it. While benefiting by his wards estate, it is to be hoped that the prior, whose calling should have made him love learning, did not neglect his education. When he came of age, Robert, who had a taste for field sports, obtained from the king a charter of free warren in his manors of Newton and Walton, and in his manor of Woolston, in the parish of Warrington. Without such a license no man in those days could justify taking birds or beasts of warren, even on his own land, and there are instances of keen sportsmen who, having obtained such a license, actually sold their lands and retained the right to sport over them. The beasts and birds of free warren, in opposition to those of the forest, were hares, conies, and roes, partridges, rails, and quails, woodcocks and pheasants, mallards and herons.

Robert, who had an eye to profit as well as pleasure, in the following year obtained the kings charter for a fair and market at his manor of Newton. Those were times when it was easier to bring goods to the customers than for these to go to seek the goods. Inland trade, we are told, was then heavily crippled by the badness and insecurity of the roads. It was a costly days journey to ride through the domain of a lord abbot, or an acred baron?the bridge, the ferry, the hostelry, and the cause-way across the marshes?had each its perquisites, and Robert therefore shcwed his prudence by his attempt to obviate for his retainers and tenants some of these inconveniences. But he was at the same time strenuous in asserting and maintain-ing his rights. Ever since the Domesday Survey the church of Wigan had belonged to the Fee of Makerfield, and when, in 6 Ed. I, 1278, an attempt was made to deprive him of the right of patronage of this living, he manfully and successfully resisted it.

At the same time he set himself to reclaim from the Crown his family inheritance at Prestatyn, and he presented a petition in which he boldly set forth his rights. In this attempt, however, he did not succeed, but the statement of his pedigree set forth in the petition has enabled his descendant to frame the pedigree which has been mentioned before.

But while Robert was thus mindful of his temporal interests he was not regardless of the spiritual wants of Newton. The advowson of Winwick, within which parish Newton was situated, belonged to the priory of Nostell, and with the priors consent Robert seems about this time to have built a chapel at Rokeden, near his manor house in Newton, and to have made " Roger Clericus de Newton " its first priest. (Gregsons Fragments, 322.) In 13 Ed. I, 1284, while Richard de Wartrea (or Wavertree) presided over Nostell, Robert obtained his license to have a chantry in his chapel at Rokeden, on the ground that Newton was at an inconvenient distance from Winwick ; and of this chantry, which he en?dowed with X3. 1s. 7d. a year, he made William de Heskayt the first incumbent. For the privilege which the prior had granted him Robert gave " to God and St. Oswald the king " an annual rent of xiid. to find a light for St. Mary the Virgin, " on St. Oswalds day, in the Church at Winwick for ever." (Not. Cest., Chet. So., ii, 262.) When the chantry fell at the Reformation, its endowment of X3. Is. 7d. was continued, and became the nucleus of the present endowment of Newton chapel, and thus the founders good deed has reached further than he ever dreamed of. Thomas Gentill was the chantry priest in 1312, and William de Rokeden in 22 Ed. III, (1349.) ( Lan. Chantries, Chet. So., 74, 75.) Henry de Seftun, who occurs as a witness to a Newton charter about this time, and who describes himself as bailiff of Makerfield, was probably Robert Fitz Roberts reeve. A little later Richard Phyton was Roberts seneschal, and Richard de Bradshaw his bailiff at Newton. But from early times there was also a kings bailiff of the hundred of Newton. Thus, William, Earl of Boulogne, Moreton, and Warren, son of King Stephen, who died in 1160, granted the office of kings bailiff of Makerfield to Walter de Waleton, and King John, in the first year of his reign, confirmed Henry, the son of Gilbert, the son of Walter, in the office. In 20 Ed. I, (1292,) when there was a general questioning of all rights, Richard de Waleton, a descendant of the first grantee, appeared and successfully maintained his right to be the kings bailiff, not only of Newton hundred but of West Derby also, and to this day the bailiff of Newton is regularly called among the nomina ministrorum at the Lanca?shire assizes.

It was at this time that the burgesses of the borough of Wigan shewed their strange notion of justice. William le Proctor being indicted for stealing a bull, one Henry Crowe, at his request, became surety for his appear-ance, whereupon Proctor was discharged and his surety was detained ; and when Proctor failed to give himself up, the borough hanged the surety and allowed the principal to escape. (Hist. Lan., iii, 532.) Those were not the days of Damon and Pythias.

Robert Fitz Robert Banastre married Alice, the daughter of Gilbert Woodcock, and was living in 1289, but he died soon after, leaving his widow surviving. They had issue a son and a daughter ; James, who married Elena, the daughter of Sir William le Boteler, Baron of Warrington, by whom he had issue, through whom the barony of Newton was trans?mitted to her descendants, and Clementia, to whom, on her marriage with William de Lea, her father made a grant of Mollington Banastre, in Cheshire. James, the heir apparent, in the direct line of succession, the last male of his house, doubtless to his fathers great sorrow, was carried to the grave before him.

Not to interrupt the regular sequence of the barons of Newton, we stop here, where the line ends in a female, to notice a few of the Banastres, who, though evidently persons of note, are not in the direct Newton line of succession.

One of these, Thomas Banastre, in 1298, was commanded to raise 2,000 men in Lancashire, and march with them to the king at Berwick-upon-Tweed, to assist in reducing Wallace, who had succeeded in rousing his countrymen to rise against the English. (Hist. Lan., i, 270.) The Banastre name doubtless drew some of the spirited Newton men to join in this campaign, which proved very disastrous to the English. Thomas, however, returned home safely, and in 1314 he was one of the knights of the shire for the county of Lancaster, an office in which another of his name and lineage, William Banastre, had served the county ten years before. In 1307, Richard Banastre was a burgess in Parliament, for Preston, and a little later three of the family were friars at Warrington, one of whom, Geoffrey Banastre, was made prior of the house.

The story of another of them, Sir Adam Banastre, requires to be told a little more at length. He had married the daugh?ter of Sir Robert de Holland, and bore for his arms, argent, a cross patonce, sable?arms which were very distinct from those of the barons of Newton. The times were disorderly, and Sir Adam greatly forgot his knightly manners, when he, with six others in his company, fell upon the Prior of Lancaster, at Poulton, and after having cruelly wounded him and his retinue, carried all of them off to Thornton, and there threw them into prison. (Reg. Stae. Mariae Lan. MS., and Hist. Lancaster, 234.) Afterwards, with a view of in?gratiating himself with the king, he raised his standard against Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, his patron, and professing an intention to relieve the king from his influence and ill practices, he collected a force of 800 men, with which he entered upon the earls estates, and possessed himself of the arms and money there laid up for the prosecution of the Scottish war. Hastily mustering some forces, the earl came up with his enemy near Preston, when Sir Adam rushed upon him so furiously that his troops began to give way, but a reinforcement coming up, Sir Adam, in his turn, was com?pelled to make a precipitate retreat, when a great number of his followers were slain, and he himself was so closely beset that, after escaping for a time, he took courage from despair and rushed boldly on his pursuers, who at last overcame him, and having cut off his head sent it to the earl as a trophy. (Hist. Lan., i, 270.)

All this, which took place in the 9 Ed. II, (1315,) might formerly be read recorded on a tablet in Lichfield cathedral. In the windows of Warrington friary there were formerly three figures painted in glass, one of which had a banner with the arms of Lancaster, and was undoubtedly meant for Earl Thomas ; another, with a banner, bore the arms of Holland, and was as certainly meant for Sir Robert Holland ; and the third, of which there is a second representation, had no banner, but had an antique shield with the arms argent and the cross patonce sable upon it, the same that were borne by both Sir Thomas and Sir Adam Banastre, for one of whom, and probably for the latter, who had married Sir Robert Hollands daughter, the figure was intended. But for which ever of these two knights the portrait was meant, it probably owed its appearance in the priory window to Geoffrey Banastre, the prior. It was not a flattering likeness, however, for art had not then achieved the triumphs it has since won, nor had portrait-painting then earned the commendations since bestowed on it by a Liverpool bard of venerated name, to whom its Mount Pleasant was a Parnassus :-

Tis only paintings powr

Can bring the much lovd form to view

In features exquisitely true;

The sparkling eye, the blooming face,

The shape adorned with every grace ;

To natures self scarce yield the doubtful strife

Swell from the deepning shade and ask the gift of life.

And again, addressing the ,same art in another page, he says :-

No spectre forms of pleasure fled

Thy softening mellowing tints restore,

But thou canst give us back the dead,

Een in the loveliest looks they wore.

Only one other Banastre, and he the greatest of them all, Sir Thomas Banastre, an early Knight of the Garter, yet remains to be noticed. This knight, the son of a Sir Adam and Lady Petronilla Banastre, of Claughton, the heiress of Singleton, did good service in the engagement against the Spaniards, under the Earl of Lancaster, and in 1360 he attended the king in his wars in France. At Bourg la Reine he received knighthood from the kings own hand, and then undertook an enterprise of some daring with the celebrated Sir Walter Manny before the barriers of Paris. He next attended the Black Prince, and in 1366 took part in the battle of Najara, and the next year, when the King of France had sent the King of England a defiance about the Fouage or hearth money, he went with a force into Aquitaine. In 1369 he led an inroad into Anjou, where, having the misfortune to be taken prisoner, he was detained until there was an exchange of prisoners, when he was exchanged for the Sire Caponnel de Caponnat. In 2 Richard II, Sir John Arundel (then marshal of England) with his " good knight," Sir Thomas Banastre, as Froissart calls him, was ordered to conduct an army into Bretagne, when the fleet being overtaken by a violent tempest was driven into the Irish Sea, where the ship in which Sir Thomas was, struck upon a rock and he was drowned on 16th Dec., 1379. The celebrated Cheshire hero, Sir Hugh Calveley, who was in the same ship, narrowly escaped the same fate at the same time. The Banastre sword which belonged to Sir Thomas was long preserved and shown at Windsor, as the relic of a valiant commander and one of the distinguished Knights of the Order of the Garter. (Beltz Memorials of that Order, 208.)

After this digression we return to our account of the barons of Newton.

James Banastre, the son and heir apparent of the last baron, having, as we have already stated, died without male issue in the life time of his father, the great Fee of Maker-field, on his fathers death, passed to Alice, his only child and heiress. Whilst still very young, she was contracted in marriage to John le Byron, the younger, who, in 20 Edward I, (1392,) pleaded to a quo warranto that he, in her right, was entitled to have free warren in Walton, Newton-in-Makerfield, and Woolston, and to have infangthief and gallows in Newton ; but in consequence of its appearing that Alice was under age the inquiry was adjourned.

The two last items of the claim, however, give us a glimpse of the extent of the jurisdiction of the manor courts of Newton in ancient times. The privilege claimed by the " gallows " was no less than the right to execute any criminal convicted of a capital crime in the manor court by the lords own official and on his own gallows tree. This privilege was exercised by the Baron of Kinderton by his hanging one Stringer, convicted of murder in his court, so late as the time of Queen Elizabeth, and a croft in Newton still preserves the memory of the place where

its fatal tree once stood.

John le Byrons marriage appears to have been void either for want of Alices consent when she came of age, or by reason of his own early death. (History of Lancashire, Harlands edition.) It was not thought fit, however, that a great inheritance won with the sword should rest in a distaff, and Alices hand and lands were soon afterwards sold by Edmund Crouchback, Earl of Lancaster, to John, son of Robert de Langeton, of West Langeton, in Leicestershire, for 250 marks, who thus, in her right, became Baron of Newton and Lord of the Fee of Makerfield, and on the earls death soon afterwards John and Alice were found to have held under him one knights fee in Lancashire.

The honour of the Fee of Makerfield, which had been sustained for two centuries by one great house, suffered no diminution in passing to another, the house of Langton. Under Alices new name we are reminded of one of Englands greatest men, Cardinal Langton, who threw the shield of the Church over the secular arm which extorted from King John the charter of our liberties at Runnymede. Little did Pandulph know the metal of his man when he made it a special article of charge against the king that he did –

Force perforce,

Keep Stephen Langton, chosen Archbishop

Of Canterbury, from that holy see.

King John, Act iii, Scene 1.

And as little did Pope Innocent know the service he was rendering when he so vehemently insisted that the king should enthrone the cardinal, but he plainly saw his error afterwards when he as vehemently insisted on his being deposed.

Stephen had a brother Simon, who, about 1216, was elected Archbishop of York ; but the pope, who had then learned to know the Langtons better, set aside the election. In 1264 another of the name, William Langton, being elected Arch-bishop of York, another pope, who had inherited a dread of the Langton name, set aside his election also.

But notwithstanding the papal antipathy the fame of the Langtons had suffered no diminution when Alice entered into the family. Her husbands brother, who singularly enough was called like himself, John, was Bishop of Chichester and Lord High Chancellor of England, while Walter Langton, who was probably her husbands cousin, filled the see of Lichfield, and was at that time busy in changing Upholland church, near Wigan, from a college to a Benedictine priory. (Hist. Lane., iii, 558.) Alices husband, who was knighted by the honour-giving hand of Edward I, obtained, through his brothers influence, on the 14th February, 29 Edward I, (1300,) a charter of confirmation and enlargement of the grant made to his ancestor of markets, fairs, and free warren at Newton and other places.

The new charter expressly grants Sir John a weekly market, on Thursday, at Walton-le-Dale, with a three days fair there yearly, on the eve, the day, and the morrow of St. Luke; and also a weekly market at Newton on Saturday, and two yearly fairs of three days each, one on the eve, the day, and the morrow of St. John ante portam Latinam (6th May), and the other on the eve, day, and morrow of St. Germanus the Confessor (31st July) ; and also of free warren in Newton, and the demesnes of Lowton, Golborne, and Walton-le-Dale.

It is observable that neither of the Newton fairs is now held on the charter day, but each is held eleven days later, which is the result of the change of style in the last century, when the people seem to have kept superstitiously to the original day, as if that and that only could be the saints anniversary. To all fairs there is incident what is called a court of pie powder, and I extract from a record of such a court, held at New Sarum, this curious incident to show the extent of the courts power. At this court, held in the Canons Close in Whitsun-week,

in the 35th year of the kings reign, Clement Slegge was attached by his body for picking the pocket of one John Thomas, of London, capper, of an account book ; and the said Clement being charged with the offence and being unable to disprove it, was adjudged to stand in the pillory for two hours during the fair, which punishment he accordingly underwent. (Madoxs Formulare Anglic., p. 18.)

Sir John and dame Alice Langton, on 29th April, 32 Ed. I, (1304,) levied a fine of all their lands in Walton-le-Dale, Newton, and Lawton, and the advowson of the church of Wigan, and by it they settled all those lands upon themselves for life, with remainder to the heirs of the said Sir John, born of the body of the said Alice, with remainder to her right heirs for ever.

On the 11 th April, 11 Edward II, (1318,) as if to secure Sir John to his side in the views he was then meditating, Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, granted him an inspeximus and confirmation of Henry de Lacys ancient charter to Robert Banastre.

Alice, Sir Johns young wife, was certainly living in 1304, but she was as certainly dead before 18 Edward II, (1325,) when Robert de Hollands lands were expressly found to be held under her surviving husband.

On the 2nd July, 6 Edward III, 1332, Sir John, by a deed in Norman French, appointed his reeve, Richard de Newton, his attorney, to give Gilbert de Haydoc seisin of ten acres in Newton wood ; and the Langton seal to this deed bears the original arms of the Langtons of West Langton.

It was in Sir Johns time that William is Gentyl, the most irregular of Lancashire sheriffs, being ordered to make a return to Parliament of two knights of the shire, returned of his own authority, and without consulting the county, Gilbert de Haydoc, one of Sir Johns near neighbours, and with him another person, to be such knights, and paid them X20 for their expenses, whereupon the county lodged a threefold complaint against him ; first, that he had made the return of his own will and without their assent ; secondly, that he had paid Gilbert and his colleague ?20, while as good men might have been found for X10, or even for ten marks ; and thirdly, that his bailiffs had levied as much money for their own use as they had paid the knights. The real gravamen of the complaint was that the sheriff had over-rated the value of the services of his two nominees. (Hist. Lancashire, i, 300-1.)

In Sir John Langtons time also there occurred at Newton an event which has obtained more notice than almost any other of its local circumstances. In the early years of the reign of Edward II, Sir William Bradshaw, of Haigh, a great traveller and soldier, having left his home, remained abroad so long without any tidings being heard of him that he was given up for dead, and his wife took to herself a second husband, a certain Welsh knight. After a time, however, it happened that Sir William returned, in a palmers habit, and came amongst the poor to his own gate, where being recognised by his wife, she wept over him tears of joy, for which the Welsh knight took upon him to chastise her, whereupon Sir William made himself known to his tenants, and the Welsh knight having wisely consulted his safety by flight, Sir William followed and overtook him near Newton Park, and there slew him upon a stone called " the Bloody stone," which has ever since been said to retain marks of the Welsh knights blood. To atone for her share as the innocent cause of this offence, Mabel, Sir Williams widow, founded a chantry in Wigan church, to which the first priest was presented in 1328, and about a mile from it erected the cross called Mabs cross, from which she vowed to walk barefoot once a year to the chantry by way of penance.

Sir John de Langton, who had two sons, Robert and John, must have died about the 7 Edward III, (1334,) for in the following year we find his son Sir Robert in possession of the barony of Newton. He married Margaret, who is thought to have been a daughter of William, son of Henry de Orrell, for in 14 Edward III, (1340,) some of the Orrell estates seem to have been settled on him and his wife and their issue. The next year he had a license to embattle (kernellare) his house at Newton. This house, the site of which now lies buried beneath the railway embankment, stood on the rock above the brook, a little to the north of the present picturesque old hall at Newton. Its moat, which had been cut out of the solid rock, was perfect until the railway, with its iron heel, rushed over it, and buried it beneath a high mound, which, if it had been thrown up in front of the house in an earlier age, would have been its best defence against a surprise. (Not. Cest., Chet. So., 273. Notes and Queries, ix, 220, 270.)

In 1346, Sir Robert, who was serving under the king in his French wars, probably shared in the glories of the great day at Crescy, for at the siege of Calais, shortly afterwards, he was knighted, and probably there witnessed a dramatic incident, the humble submission of the men of Calais, and heard the queen graciously interceding for their pardon. About this time there occur several Newton charters, some of which prove the times to have been very simple. They mention John the shepherd, ,Thomas the herdsman, and John the serjeant (serviens), who, I suppose, was the lords bailiff or reeve. All these were employments of duty or business ; but John the piper, who was a minister of pleasure, is also mentioned. His performance, which had not much music in it, was -probably much like that which Benedick says the recreant Claudio had learned to love:

I have known when there was no music with him but the drum and fife,

and now he would much rather hear the tabor and pipe.

Much Ado About Nothing.

This music, which was sufficient to mark time, had little else to recommend it, and at many a village ball this now antiquated instrument formed the whole band within times of living memory.

In 1346, the king, being about to make the Black Prince, his eldest son, a knight, levied an aid for that purpose, to which Sir Robert was assessed at half a knights fee for his West Langton lands.

Sir Robert died on Sunday before the feast of St. Michael, 26th September, 35 Edward III, (1361,) leaving three sons, John, Richard, and Robert. Richard probably became Rector of Wigan, Robert became a serviens ad arma, and took Hindley and the original paternal property in Leicestershire, with a carucate of land at Hendon in Middlesex, while the barony of Newton and Walton-le-Dale devolved upon his grandson Ralph, the son of his son John, who had died in his lifetime.

Sir Ralph Langton, in 1367, obtained the bishops license to have an oratory for three years in his manor house at New-ton, (Not. Cest., Chet. So., ii, 272) ; and in 1370, he pre?sented his clerk, James Langton, to the living of Wigan. In 10 Richard II, when he was 45 years old, he was examined in the friary at Warrington as a witness in the celebrated suit of arms between Scrope and Grosvenor, and gave evidence in favour of the latter.

Sir Ralph, probably in consequence of feeling the approach of age, on the 12th Dec., 1405, obtained a renewal and con?firmation of his privilege of a chantry at Rokeden, which must have been near his house, and he had the bishops further consent to have divine offices celebrated before him and other faithful christians at Rokeden in his chapel there, without any burden upon the mother church. (Not. Cest., Chet. So., ii, 272.) It was about this time that John Dauke left to William

Langton, his spiritual father, to whom he was attached, the use for his life of a book (unius libri) which Richard le Scroop carried in his bosom when he was beheaded, supplicating him to cause the said book after his decease to be chained near the place where the said Richards body lay, there to remain for ever. (Whitakers History Whalley, 484.) On the same principle a copy of the Koran is. placed in the tomb of the Sultan Tayloon in his noble mosque at Cairo.

Sir Ralph, who married Joan the daughter of William de Radcliffe, died in or about 7 Hen. IV, (1406,) leaving his wife surviving, who was still living in 8 Hen. V, (1420.) They had several children, of whom the eldest,

HENRY LANGTON, esquire, succeeded to the barony of New-ton. He married Agnes, the daughter of John de Davenport, and died 14th Sept., 7 Hen. V, (1419,) leaving his wife surviving. He was succeeded by his eldest son,

Sir RALPH LANGTON, knight, who married a wife named Alice, and died 6th Feb., 1431, leaving her surviving. Sir Ralph was succeeded by his son Henry, who was 12 years old at his fathers death.

HENRY LANGTON, esquire, baron of Newton, married Eliza?beth, and died 13th Sept., 1471, leaving his wife, who died 17th Nov., 1472. Sir Richard Langton, his eldest son, who next succeeded to the barony, marched to the north with the Duke of Gloucester, afterwards Richard III, and Lord Stanley, and was made a banneret by the latter at Hutton Field in 1482. The Lancashire men were much mixed up with this march to the north, and upon it the Duke of Gloucester, according to tradition, slept at Bradley, near Newton ; but between his and Lord Stanleys party some jealousy at last broke out, and there was a skirmish at Salford, in which the Dukes banner was taken, possibly by one of the Langton Party, since it was hung up as a trophy in Wigan church, and a ballad was made about it, which began thus*

Jack of Wigan, he did take

The Duke of Gloucesters banner,

And hung it up in Wigan church,

A monument of honour.

(Halsteds Richard III, vol. ii, 67.)

* In the Cole MSS, British Museum, another version of the ballad says

Jack Morris of Wigan brought the Dukes banner To Wiggan kirk, it served there forty year.

Sir RICHARD LANGTON married Isabella, the daughter of Sir Thomas Gerard, of Bryn, and died on 23rd August, 1500, leaving his wife surviving. He was succeeded by his eldest son,

RALPH LANGTON, who married Joan, the daughter of Sir Christopher Southworth, and dying on 29th July, 1503, was succeeded by his son RICHARD, who dying under age, was followed by his younger brother,

Sir THOMAS LANGTON, who married Elizabeth, the daughter of Lord Monteagle, the hero of Flodden, to whom the wardship of the heir of the barony had been granted by his mother. In his day, the antiquary Leland, who visited Newton, thus de-scribes it :–

" Newton, on a brook, a little poor market, whereof " Mr. Langton has the name of his barony." +

+ In 2 Ed. VI, (1548,) John Dunster, aged 40, was the priest of the Newton chantry.?(Lan. Chantries, 74, 75.)

In 1553 Newton was ordered to find four of the armed men who were to be provided by Winwick parish ; and in 1557 Sir Thomas Langton received orders to command fifty men of the Lancashire force ordered to be raised to resist the Scots. (Hist. Whalley, 533.) In 1556 he filled the office of high sheriff of Lancashire, and in 1557 he served the same office again. In neither of these years were the times quiet, and Sir Thomas no doubt found his office as onerous as honourable. In the year 1558 he obtained for Newton, by charter from the queen, the right to send two burgesses to parliament. Sir Thomas was the owner of nearly the whole borough, and his steward was the returning officer, and if he had so pleased he might have nominated himself to be one of the members, but he does not seem to have done so, and as he did not sit for any other place, he perhaps did not covet parliamentary honours. In the parliament of 1558 and 1559 Newton was represented by Sir George Hazard, knight, and Richard Chetwode, esquire, and in that of 1563 by Francis Alford and Ralph Browne, esquires. We know nothing of these persons. Let us hope, therefore, that they were selected by Sir Thomas, honestly, on public, and not on private grounds ; but the newness of the queens reign and the unsettled state of the times may have induced Sir Thomas in sending them to gratify the queen in the way mentioned in Clarendons State Papers. (P. 92 c.Humes Hist., v. 9, note.)

Elizabeth, the first wife of Sir Thomas Langton, having died before him, he then married Anne, sometimes called Anne Slater, the daughter of Thomas Talbot, a younger son of John Talbot of Salebury. Sir Thomas died on the 14th of April, 1569, leaving dame Anne, his widow, surviving him, and by his will, dated the 4th of April preceding, in which he calls himself " Thomas Langton, of Walton-in-le-Dale, in " the county of Lancaster, knight, Baron of Newton," after reciting a deed bearing date the 4th August, 5 and 6 Philip and Mary, (1558,) being a settlement of his great possessions in many different places, and reciting how the same were disposed of by it, he directed his body to be buried amongst his ancestors, in the chancel of the church of Walton-le-Dale, towards repairing which church he gave the sum of ?20. His cousin [grandson] Thomas Langton, was to have his gold chain and a standing silver cup with the gilt cover, whereupon was graven the word " heirloom," his greatest silver goblet and cover, one silver cup with the cover parcel gilt, made after the fashion of a glass, his silver piece pounced, (a box like Hotspurs " pouncet-box,") one pounced silver plate, one silver drinking-cup with two handles, two of his best silver gilt salts and their covers, one dozen of the best silver spoons, one of them gilt; one silver piece, two great brazen pots in the kitchen, one great copper pan ; with a wain, plough, and all other instruments belonging to husbandry, and all his harness and armour. And afterwards, amongst many other legacies to his servants and others, he gave to E. Rishton, in recompense of her wages for long service, ?40. To his priest, Thomas Edmundson, he gave an annuity of 40s. for four years, and to his executors, during four years, ?6. 13s. 4d., which is expressed to be for a remembrance of him " when he was gone." (Lan. and Cites. Wills, Chet. Soc., part ii, 246.)

Sir Thomas Langton was succeeded by his grandson, another Thomas, the son of his youngest son, Leonard Langton, who, under the settlement of 1558, took the family estates as tenant in tail. Like his grandfather, he seems, for the greater part of his life, to have been content with nominating others to represent the borough of Newton in Parliament, without seeking to take that honour upon himself. In the year 1571, the pope having issued his bull of excommunica?tion against the queen, in which, mistaking his power, he idly affected to deprive her of the crown and to absolve her subjects from their allegiance, one Felton, who had been bold enough to affix the bull to the gates of the Bishop of Londons palace, obtained by it what he probably desired and certainly deserved, the crown of martyrdom, for he was immediately seized and put to death as a traitor. Parliament, which had not met for five years, was now called together, it being thought proper that the nation should mark its sense of the popes attempted outrage upon the queen and the consti?tution. (Humes Hist. Enq., v, 172.) This Parliament met on the 3rd of April, 1571, and Newton was represented in it by Anthony Mildmay and Thomas Stoneley, esquires, its two burgesses. The first of these burgesses was probably one of the Northamptonshire family. (Collins Peerage, iii, 294.) But we have not discovered who the second was or how he was connected with Newton.

On the 23rd April, 1573, dame Anne Langton, the widow of the late Sir Thomas, made her will, by which, amongst other legacies, she gave the crucifix of gold which she was accustomed to wear about her neck to her cousin William Ffaryngton. She left ?20 to her daughter, Katheryn Langton, which she says she owed her, but she mentions no others of the name. The will was proved in the following June, and to it there is attached a long and very minute inventory of her effects. (Lan. and Ches. Wills, Chet. Soc., part iii, 58.)

On the summoning of a new parliament in the following year, 1574, the burgesses for Newton were John Gresham, Esq., and John Savile, Esq., of whom the latter was probably a barrister, and the person of his name, who in 1598 was made Baron of the Exchequer.

In 1577 a parliament was held, which after sitting long had done so little that the queen, addressing the speaker, Popham, at its close, said, " Mr. Speaker, what have you " passed ?" to which he naively replied, " Please your majesty, five weeks." It is to be regretted that the members for Newton were not present to hear this passage of wit.

In the year 1584, the queens rule being threatened with conspiracies, she called a new parliament, to which Newton sent Robert Langton, Esq., of Lowe, a collateral relation of the baron of Newton, and Edward Savage, as their burgesses ; and in 1586, when the queen was again threatened, the same members were again returned. But in the following year, which was that of the Spanish armada, a change was made, and Edmund Trafford, Esq., of Trafford, and Robert Langton, Esq., of Lowe, were returned to represent Newton.

In the night of the 20th and 21st Nov., 32 Eliz., (1589,) in consequence of some cattle of widow Singletons being impounded by Mr. Hoghton, of Lea hall, between Preston and Kirkham, Mr. Langton of Walton, the Baron of Newton, assembled his retainers, to the number of eighty, and with them sallied out against Mr. Hoghton, and being met by the latter at the head of about thirty of his followers, a regular engage?ment ensued, in which Mr. Hoghton and William Bawdwen, one of Mr. Langtons people, were slain, and he himself, grievously wounded, was carried off the field to Broughton tower. For this offence the Baron of Newton and others were indicted, and while they lay in prison awaiting their trial the Earl of Derby, then Lord Lieutenant of the County, wrote a letter to Lord Burleigh, in which he stated that, moved by the earnest desires of a number of poor men, his sense of duty to her majesty, and foreseeing some danger likely to ensue to the county, he thinks fit to acquaint his lordship with a troublesome cause between Mr. Baron of Walton,*

* Walton-le-dale being the principal residence of the barons of Newton, they were frequently spoken of as barons of Walton ; but though a superior lordship, with jurisdiction over five appurtenant manors, it was not a barony. This lord-ship elected its own coroner.

;and Mr. Houghton. He informs him " that the gentlemen were " only in peril of burning in the hand, while the poorer and " less guilty offenders were in much more danger ;" and he entreats Lord Burleigh to obtain for them a pardon before the assizes, since many of them could not read, and were there-fore likely to lose their lives without her majestys most gracious favour. He points his lordships attention to the fact, " that the better sort of the offenders were so great in " kindred and affinity, and so stored with friends, that if they " should be burnt in the hand there would grow out of it a " great and ceaseless quarrel ;" and he ends by suggesting " that the parties should be subjected to banishment for a " time, as the safest and best course to satisfy both sides." We are startled to think of the inequality of punishment here described as existing in those days, and we are not less surprised to find a lord-lieutenant writing to interfere with the course of justice, after a riot which had embroiled the county.

It does not appear what was the result of the lord-lieute?nants letter, but the Baron of Newton surrendered his lord-ship of Walton-le-dale to Mr. Hoghtons family, and made his peace with this weregeld after the ancient fashion of the Saxon times. In the parliament called in 1592 to grant the queen a subsidy towards the expenses of the government, Edmund Trafford and Robert Langton, esquires, were again returned as members for Newton. It was in this parliament that, in reply to the speech of the speaker, Sir Edward Coke, making the usual three requests, of freedom from arrests, of access to her majestys person, and of free liberty of speech, that the queen, by the mouth of Puckering, the lord keeper, told him that " they (the house) must know what was the " liberty they were entitled to, that it was not a liberty for " every one to speak what he listeth, or what cometh into his " brain to utter ; for that their privilege extended no further " than a liberty of aye or no." The members for Newton probably sat patiently to hear the lord keeper give Sir Edward this rebuff, which he had brought upon himself by his obse?quiousness in the speech in which he announced his election. " This," said he, " is only a nomination and no election, until " your majesty giveth allowance and approbation." (2 Has-sell, 154.)

About this time, for some reason which we cannot explain, unless it be the plea of concealed lands, the Fleetwoods, Sir Thomas Langtons kinsmen, had made an assignment of their reversion of the Langton estates to the queen but in the year 1594, they entered into an agreement with him to revoke and make void such assignment, and by a deed of the 15th July, in that year, and a fine levied in pursuance of it, Sir Thomas, describing himself as of Walton-le-Dale and Baron of Newton, settled the barony, manor, and seigniory of New-ton, with all courts, markets, fairs, liberties, and franchises, and the nomination, election, and appointment of two bur?gesses to parliament, which had been used by the baron, lord, or owner of the said barony, and after such election made to be sent to the parliament as burgesses for the borough of Newton, and all manors, messuages, lands, and hereditaments in Newton, Lawton, Leigh, Penyngton, Makerfield, Eccles alias Egresfield, Golborne, Kenyon, Crofte, Southworth, Middleton, Arbury, Houghton, Fearnhead, Poulton, Woolston, Hulme, Winwick, Haydoc, Ashton, Pemberton, Orrell, Billinge, Wynstanley, Ince, Hindley, and Abram, within the fee of Makerfield, or in the parishes of Warrington, Winwick, and Wigan (except the advowson of the rectory of Wigan, and all messuages theretofore used in severalty in Lawton, and the tenements and land thereto belonging, in Wigan aforesaid), to the use of Sir Thomas himself for life, with remainder to the use of his first and other sons successively in tail male, with remainder to the use of Thomas Fleetwood, esquire, of Calwich, in the county Stafford, and his heirs for ever; and in return Thomas Fleetwood on his part engaged to revoke the assignment which he had made to the queen of the Langtons reversions.

On the 24th October, 1597, when the queens necessities again obliged her to call a parliament, the only member re-turned for Newton was their old member Robert Langton, esquire, of Lowe.