The ancient parish of Winwick lies between Sankey Brook on the south-west and Glazebrook and a tributary on the north and east, the distance between these brooks being 4½ or 5 miles. The extreme length of the parish is nearly 10 miles, and its area 26, 502 acres.

The highest ground is on the extreme north-west border, about 350 ft.; most of the surface is above the 100 ft. level, but slopes down on three sides to the boundaries, 25 ft. being reached in Hulme in the south. The geological formation consists of the Coal Measures in the northern and western parts of the parish, and of the Bunter series of the Nèw Red Sandstone in the remainder. Except Culcheth, which belonged to the fee of Warrington, the whole was included in the barony of Makerfield, the head of which was Newton.

The townships were arranged in four quarters for contributions to the county lay, to which the parish paid one-eighth of the hundred levy, each quarter paying equally:—(1) Winwick with Hulme, half; Newton, half; (2) Lowton and Kenyon, half; Haydock and Golborne, half; (3) Ashton; (4) Culcheth, two-thirds; Southworth and Croft, a third. To the ancient ‘fifteenth,’ out of a levy of £106 9s. 6d. on the hundred, the parish contributed £8 3s. 6¾d., as follows:—Newton, £1 10s.; Haydock, 10s. 9¼d.; Ashton, £2 14s. 5¼d.; Golborne, 8s.; Lowton, 15s. 8d.; Culcheth, £1 8s. 10¼d.; Southworth and Croft, 9s. 2d.; Middleton with Arbury, 6s. 8d.

One of the great roads from south to north has from the earliest times led through Winwick, Newton, and Ashton, and there are several tumuli and other ancient remains.

The Domesday Survey shows that a large part of the surface consisted of woodland, and Garswood in Ashton preserves the name of part of it. In the Civil War two battles were fought near Winwick. In more modern times coal mines have been worked and manufactures introduced, and Earlestown has grown up around the wagon-building works of the London and North-Western Railway Company.

The agricultural land in the parish is utilized as follows:—Arable land, 16, 258 acres; permanent grass, 4,820 acres; woods and plantations, 653 acres. The following are details:—

Newton has given the title of baron to the lord of the manor, who has, however, no residence in the parish; Lord Gerard of Brynn has his principal seat at Garswood.

Dr. Kuerden thus describes a journey through the parish made about 1695:—’Entering a little hamlet called the Hulme you leave on the left a deep and fair stone quarry fit for building. You meet with another crossway on the right. A mile farther stands a fair-built church called Winwick church, a remarkable fabric. . . . Leaving the church on the right about a quarter of a mile westwards stands a princely building, equal to the revenue, called the parsonage of Winwick; and near the church on the right hand stands a fair-built schoolhouse. By the east end of the church is another road, but less used, to the borough of Wigan.

‘Having passed the school about half a mile you come to a sandy place called the Red Bank, where Hamilton and his army were beaten. Here, leaving Bradley park, and a good seat belonging to Mr. Brotherton of Hey (a member of Parliament for the borough of Newton) on the left hand, and Newton park on the right, you have a little stone bridge over Newton Brook, three miles from Warrington. On the left hand close by a water mill appear the ruins of the site of the ancient barony of Newton, where formerly was the baron’s castle.

‘Having passed the bridge you ascend a rock, where is a penfold cut out of the same, and upon the top of the rock was lately built a court house for the manor, and near to it a fair re-edified chapel of stone built by Richard Legh, deceased, father to Mr. Legh, the present titular baron of Newton. There stands a stately cross, near the chapel well, adorned with the arms belonging to the present baron. Having passed the town of Newton you leave a cross-road on the left going to Liverpool by St. Helen’s chapel. You pass in winter through a miry lane for half a mile; you leave another lane on the left passing by Billinge. . . .

‘Then passing on a sandy lane you leave Haydock park, and (close by the road) Haydock lodge, belonging to Mr. Legh, and going on half a mile you pass by the chapel and through the town of Ashton, standing upon a rocky ground, which belongeth to Sir William Gerard, bart., of Brynn, who resides at Garswood, about a mile to the east (sic). Having passed the stone bridge take the left hand way, which though something fouler is more used. You then pass by Whitledge Green, a place much resorted to in summer by the neighbouring gentry for bowling. Shortly after, you meet with the other way from Ashton bridge by J. Naylor’s, a herald painter and an excellent stainer of glass for pictures or coats of arms. Through a more open coach-way passing on upon the right leave the Brynn gate, a private way leading to the ancient hall of Brynn, and upon the left another road by Garswood to the hall of Parr, a seat belonging to the Byroms, and to St. Helen’s chapel; and thence past Hawkley to Wigan.’ (fn. 1)

INDEX MAP to the PARISH of WINWICK

Among the worthies of the parish may here be noted Thomas Legh Claughton, born at Haydock Lodge in 1808, who became Bishop of Rochester in 1867, resigning in 1890, and died in 1892; (fn. 2) also Thomas Risley, a Nonconformist divine, 1630 to 1716. (fn. 3)

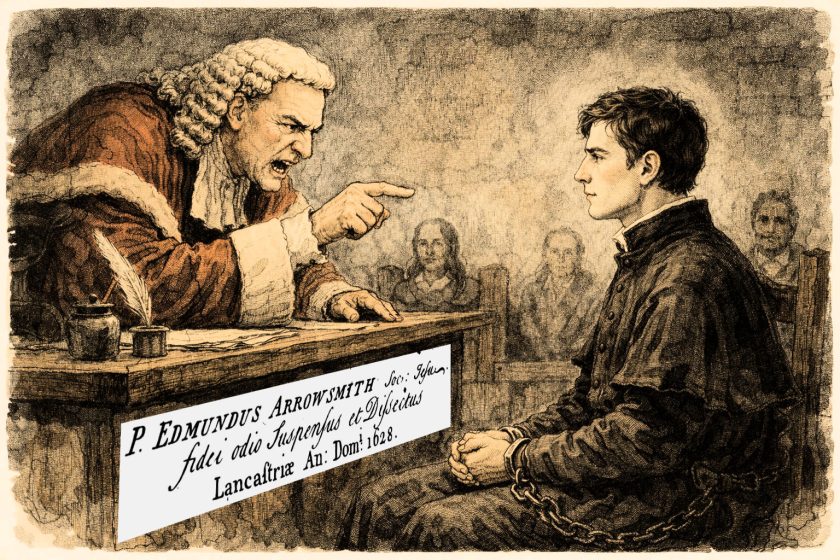

The following in 1630–3 compounded by annual fines for the two-thirds of their estates liable to be sequestered for their recusancy: Ashton, Sir William Gerard of Brynn, £106 13s. 4d.; Jane Gerard; Culcheth, Richard Urmston, £6; Lowton, Peter and Roger Haughton, £3; Southworth, Christopher Bow of Croft, £2 10s. (fn. 4)

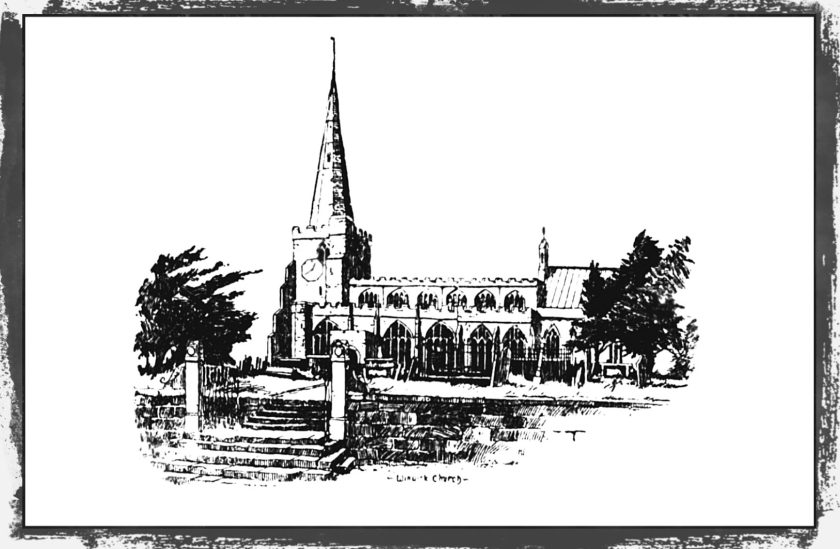

CHURCH

The church of ST. OSWALD has a chancel (fn. 5) with north vestry, nave with aisles and south porch, and west tower and spire. It is built of a very inferior local sand-stone, with the result that its history has been much obscured by repairs and rebuildings, and cannot be taken back beyond the 14th century; though the dedication and the fragment of an early cross, now set up outside the chancel, both point to an early occupation of the site.

The chancel was entirely rebuilt in 1847–8 in 14th-century style, the elder Pugin being the architect, and is a fine and well-designed work with a high-pitched leaded roof, a four-light east window, and three-light windows on north and south. There are three canopied sedilia and a piscina, and the arched ceiling is panelled, with gilt bosses at the intersection of the ribs, and a stone cornice with carved paterae.

The nave is of six bays, with a north arcade having pointed arches of two orders with sunk quarter-round mouldings, and curious clustered piers considerably too thick for the arches they carry, and projecting in front of the wall-face towards the nave. The general outline is octagonal with a hollow between two quarter-rounds on each cardinal face, and a deep V-shaped sinking on the alternate faces. The abacus of the capitals is octagonal, but the necking follows the outline of the piers, and pairs of trefoiled leaves rise from the hollows on the cardinal faces. The bases, of very rough work, are panelled on the cardinal faces, with engaged shafts 6 in. high, while on the diagonal faces are badly-cut mitred heads.

There is a curious suggestion of 14th-century detail in the arcade, in spite of its clumsiness, but the actual date is probably within a few years of 1600. The clearstory above has three windows set over the alternate arches, of four lights with uncusped tracery and low four-centred heads.

The south arcade, ‘from the first pillar eastward to the fifth west,’ was taken down and rebuilt from the foundations in 1836. It has clustered piers of quatrefoil section, and simply moulded bell capitals with octagonal abaci, the arches being of two chamfered orders with labels ending in pairs of human heads at the springing. The original work belonged to the beginning of the 14th century. The clearstory on this side has six windows, of four uncusped lights without tracery, under a four-centred head, all the stonework being modern.

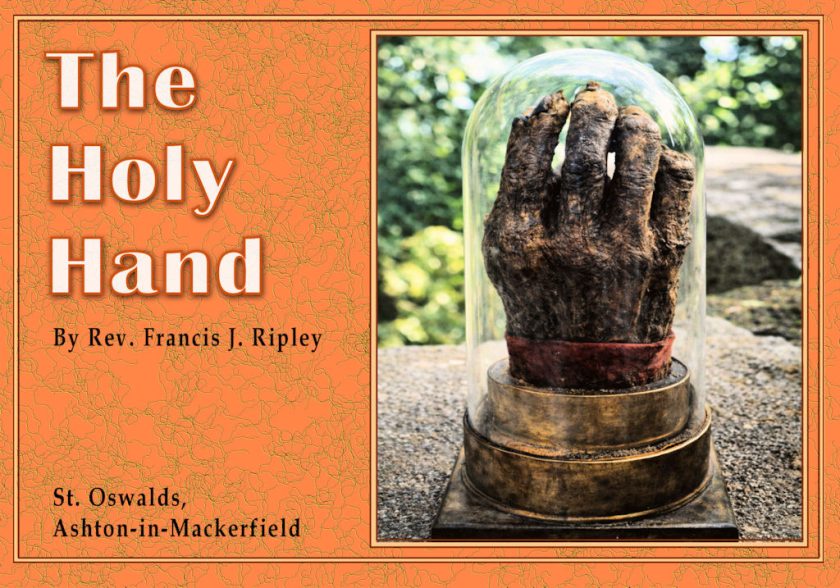

At the east end of the north aisle is the Gerard Chapel, inclosed with an iron screen, which about 1848 replaced a wooden screen dated ‘in the yere of our Lord MCCCCLXXXI.’ There is a three-light east window and two four-light windows on the north, all with 16th-century uncusped tracery. In the aisle west of the chapel are three four-light north windows with embattled transoms and uncusped tracery, and a north doorway with a square-headed window over it, of four uncusped lights. The tracery, except part in the Gerard Chapel, has been lately renewed, the original date of the windows being perhaps c. 1530–50. On the external faces of the transoms is carved the IHS monogram. The two east bays of the south aisle are taken up by the Legh Chapel, and separated by an arch at the west from the rest of the aisle. This western portion was rebuilt in 1530, being dated by an inscription running round the external cornice, and the Legh Chapel is somewhat earlier in date, perhaps c. 1500. The chapel has a small doorway on the south, a three-light window on the east, and two on the south, all with uncusped tracery, the stonework being mutilated, and in the aisle are three four-light windows on the south, with embattled transoms and tracery uncusped except in the upper middle lights, and one window at the west, also of four lights, but of different design. On the external faces of the transoms are carved roses, all the stonework being modern. The aisle has a vice at the southwest angle. The south porch is low, and the inscribed cornice of the aisle runs above it without a break. The porch has been completely refaced, and opens to the south aisle by a four-centred doorway with continuous mouldings. Both aisles and clearstory have embattled parapets and leaded roofs of low pitch. The inscription round the south aisle is in leonine hexameters, running from west to east, and is as follows:—

Hic locus Oswalde quondam placuit tibi valde;

Nortanhumbrorum fueras rex, nuncque polorum

Regna tenes, prato passus Marcelde vocato.

Poscimus hinc a te nostri memor esto beate.

Anno milleno quingentenoque triceno

Sclater post Christum murum renovaverat

istum;

Henricus Johnson curatus erat simul hic tunc.

The tower retains much of its old facing, though the surface is much decayed. It has a vice at the south-east angle, which ends with a flat top at the level of an embattled parapet at the base of the spire. The spire is of stone, and has two rows of spire lights, and the belfry windows are of two trefoiled lights with quatrefoils in the head. All the work belongs to the first half of the 14th century, and in the ground story is a three-light west window with modern net tracery, flanked by two empty niches, with below it a four-centred doorway with continuous wave-mouldings. The tower arch is of three continuous wavemoulded orders. On the west face of the tower, to the south of the niche flanking the west window on the south, is a small and very weathered carving of a pig with a bell round his neck, known as the Winwick pig. His story is that, like other supernatural agencies under similar circumstances elsewhere, he insisted on bringing all the stones with which the church was being built on another and lower site to the present site, removing each night the preceding day’s work. (fn. 6)

The roof of the Gerard Chapel is modern, but that of the Legh Chapel has heavily-moulded timbers, ceiled between with plaster panels having moulded ribs and four-leaved flowers at the centres. Below the beams, at the wall plates, are angels holding shields with heraldry. (fn. 7)

The roofs of the aisles have cambered tie-beams and braces, with panels between the beams divided into four by wood ribs. Neither roof is set out to space with the arcades or windows, the south aisle roof being of seven bays, that in the north aisle of six; they belong probably to c. 1530.

In the vestry is a very fine and elaborate 15th-century carved beam, found used up in a cottage. It has eleven projecting brackets for images, that in the middle being larger than the others, and may have been the front beam of the rood-loft. It is 15 ft. long. An altar table in the vestry dated 1725 is inlaid with mahogany, with a ‘glory’ in the middle and initials at the corners, and a monogram A T.

In the Gerard Chapel is the fine brass of Piers Gerard, son of Sir Thomas Gerard of the Brynn, 1485, and in the Legh Chapel is a second brass, now set against the east wall, with the figures of Sir Peter Legh, 1527, and his wife Ellen (Savage), 1491. Sir Peter was ordained priest after his wife’s death, and is shown on his brass tonsured and with mass vestments over his armour. Below are figures of children. There is a brass plate in the chancel pavement to Richard Sherlock, rector, 1689.

Later monuments in the Legh Chapel are those of Sir Peter Legh, 1635, and Richard Legh and his wife, 1687. On the south side of the chapel some alabaster panels with strapwork and heraldry, from a destroyed Jacobean monument, are built into the wall. (fn. 8)

There are six bells, re-cast in 1711.

The church possesses two chalices, patens, and flagons of 1786; two chalices, four patens, and two flagons of 1795; and a sifter and tray of the same date. Also a pewter flagon and basin, two large copper flagons, red enamelled, with gold flower painting of Japanese style, a gilded brass almsdish and two plates, designed by Pugin, and an ebony staff with a plated head, the gift of Geoffrey Hornby, rector, 1781–1812.

In the chancel hangs a brass chandelier, given by the Society of Friends of Warrington.

The registers begin in 1563, the paper book not being extant. The first volume contains the years 1563–1642, the entries to 1598 being copies. The next volumes in order are 1630–77, 1676–95, 1696–1717, 1716–33.

The octagonal bowl of a 14th-century font found in 1877 beneath the floor of the church now lies outside the east end of the chancel, in company with the piece of an early cross-head described in a previous volume. (fn. 9) It is much worn, but has had four-leaved flowers on each face, with raised centres, and must have been a good piece of work when perfect. (fn. 10)

ADVOWSON

‘St. Oswald had two plough-lands exempt from all taxation’ in 1066, so that the parish church has been well endowed from ancient times. (fn. 11) Possibly the dedication suggested to Roger of Poitou the propriety of granting it to St. Oswald’s Priory, Nostell, (fn. 12) a grant which appears to have been renewed or confirmed by Stephen, Count of Mortain, between 1114 and 1121. (fn. 13) In 1123 Henry I wrote to the Bishop of Chester, directing that full justice should be done to the prior and canons of Nostell, whose clerks in Makerfield were depriving them of their dues. (fn. 14) From this time the prior and canons presented to the church, receiving certain dues or a fixed pension; but beyond the statement in the survey of 1212 (fn. 15) nothing is known until 1252, when Alexander, Bishop of Lichfield, having been appealed to by the prior and the canons, decreed that on the next vacancy they should present ‘a priest of honest conversation and competent learning’ as vicar, who should receive the whole of the fruits of the church, paying to Lichfield Cathedral and to Nostell Priory a sum of money as might be fixed by the bishop. In the meantime the annual pension of 50s. then paid to Nostell from the church of Winwick was to be divided equally, half being paid to the church of Lichfield. (fn. 16) A century later it appears that a pension of 24 marks was due from the vicarage to the monastery. (fn. 17)

Nostell Priory. Gules a cross between four lions rampant or.

In 1291 the annual value was estimated as £26 13s. 4d., (fn. 18) while in 1341 the ninth of the corn, wool, &c. was valued at 50 marks. (fn. 19)

The first dispute as to the patronage seems to have occurred in 1307, when John de Langton claimed it in right of his wife Alice, heiress of the lords of Makerfield. The priors of Nostell, however, were able to show a clear title, and the claim was defeated. (fn. 20) About fifty years later the patronage was acquired by the Duke of Lancaster. (fn. 21) In 1381 the king was patron, (fn. 22) and the Crown retained the right until Henry VI granted it to Sir John de Stanley, reserving to the prior an annual pension of 100s. (fn. 23) From this time it has descended with the main portion of the Stanley properties, the Earl of Derby being patron.

In 1534 the net value was returned as £102 9s. 8d., (fn. 24) but in 1650 the income was estimated at over £660, (fn. 25) and Bishop Gastrell reckoned it at about £800 after the curates had been paid. (fn. 26) At the beginning of last century, before the division of the endowment, the benefice was considered the richest in the kingdom, (fn. 27) and its gross value is still put at £1,600. (fn. 28)

The following have been rectors:—

| Instituted | Name | Presented by | Cause of Vacancy | |

| oc. | 1191 | Hugh (fn. 29) | — | — |

| oc. | 1212 | Richard (fn. 30) | — | — |

| oc. | 1232 | Robert (fn. 31) | — | — |

| c. | 1250 | N (fn. 32) | — | — |

| — | — | Alexander de Tamworth (fn. 33) | Priory of Nostell | — |

| — | — | Augustine de Darington (fn. 34) | “ | — |

| oc. | 1287 | John de Mosley (fn. 35) | “ | — |

| 8 Feb. 1306–7 | John de Bamburgh (fn. 36) | “ | — | |

| — | — 1325 | John de Chisenhale (fn. 37) | Bishop of Lichfield | d. of J. de Bamburgh |

| 12 Dec. 1349 | Geoffrey de Burgh (fn. 38) | Priory of Nostell | d. J. de Chisenhale | |

| — | — | William de Blackburn (fn. 39) | — | — |

| oc. | 1384–5 | John de Harwood (fn. 40) | — | — |

| 23 Jan. 1384–5 | Thomas le Boteler (fn. 41) | The King | — | |

| — | — 1386 | Walter de Thornholme (fn. 42) | “ | — |

| — | — 1388 | Robert le King (fn. 43) | The Pope | — |

| 6 May 1389 | William Daas (fn. 44) | The Pope | — | |

| The King | ||||

| 3 April 1423 | Mr. Richard Stanley (fn. 45) | Bishop of Lichfield | — | |

| 11 Mar. 1432–3 | Thomas Bourchier (fn. 46) | Sir John Stanley | d. R. Stanley | |

| oc. | 1436 | George Radcliffe, D. Decr. (fn. 47) | — | — |

| 19 June 1453 | Edward Stanley (fn. 48) | Sir Thomas Stanley | d. G. Radcliffe | |

| 22 Nov. 1462 | James Stanley (fn. 49) | Henry Byrom | d. E. Stanley | |

| 25 Aug. 1485 | Robert Cliff (fn. 50) | Lord Stanley | d. J. Stanley | |

| 27 Feb. 1493–4 | Mr. James Stanley, D.Can.L. (fn. 51) | Earl of Derby | res. R. Cliff | |

| 21 June 1515 | Mr. Thomas Larke (fn. 52) | “ | d. Bp. of Ely | |

| — | — 1525 | Thomas Winter (fn. 53) | The King | res. T. Larke |

| 23 Dec. 1529 | William Boleyne (fn. 54) | “ | res. T. Winter | |

| 10 April 1552 | Thomas Stanley (fn. 55) | Earl of Derby | d. W. Boleyne | |

| 19 Mar. 1568–9 | Christopher Thompson, M.A. (fn. 56) | Thomas Handford | d. Bp. Stanley | |

| 7 Jan. 1575–6 | John Caldwell, M.A. (fn. 57) | Earl of Derby | depr. or removal of Chr. Thompson | |

| 18 Feb. 1596–7 | John Ryder, M.A. (fn. 58) | — | — | |

| 27 Mar. 1616 | Josiah Horne (fn. 59) | The King | prom. Bp. Ryder | |

| 27 June 1626 | Charles Herle, M.A. (fn. 60) | Sir Edward Stanley | d. J. Horne | |

| — | — | Thomas Jessop (fn. 61) | — | — |

| 19 Oct. 1660 | Richard Sherlock, D.D. (fn. 62) | Earl of Derby | — | |

| 24 July 1689 | Thomas Bennet, B.D. (fn. 63) | John Bennet | d. R. Sherlock | |

| 30 July 1692 | Hon. Henry Finch, M.A. (fn. 64) | Earl of Derby | d. T. Bennet | |

| 9 Sept. 1725 | Francis Annesley, LL.D. (fn. 65) | Trustees | res. H. Finch | |

| 13 Sept. 1740 | Hon. John Stanley, M.A. (fn. 66) | Charles Stanley | d. F. Annesley | |

| 18 May 1742 | Thomas Stanley, LL.D. (fn. 67) | Earl of Derby | res. J. Stanley | |

| 24 Aug. 1764 | Hon. John Stanley, M.A. (fn. 68) | “ | d. T. Stanley | |

| 7 June 1781 | Geoffrey Hornby (fn. 69) | Earl of Derby | d. J. Stanley | |

| 19 Dec. 1812 | James John Hornby, M.A. (fn. 70) | “ | d. G. Hornby | |

| — | Nov. 1855 | Frank George Hopwood, M.A. (fn. 71) | “ | d. J. J. Hornby |

| 29 April 1890 | Oswald Henry Leycester Penrhyn, M.A. (fn. 72) | “ | d. F. G. Hopwood | |

As in the case of other benefices the earlier rectors were probably married ‘clerks,’ enjoying the principal part of the revenues of the church, and paying a priest to minister in the parish. Two sons of Robert, rector in 1232, are known. After the patronage had been transferred to the Stanleys the rectory became a ‘family living,’ in the later sense.

In the Valor of 1535 the only ecclesiastics mentioned are the rector, two chantry priests at Winwick, and a third at Newton. (fn. 73) The Clergy List of 1541–2 (fn. 74) shows three others as residing in this large parish, including the curate, Henry Johnson, paid by Gowther Legh, the rector’s steward. The list is probably incomplete, for at the visitation of 1548 the names of fourteen were recorded—the rector, his curate, Hugh Bulling, who had replaced Henry Johnson; the three chantry priests and two others just named, and seven more. By 1554 these had been reduced to six—the rector, his curate, Richard Smith, two of the chantry priests still living there, but only two of the others who had appeared six years earlier. In 1562 a further reduction is manifest. The rector, Bishop Stanley, was excused from attendance by the bishop; three others appeared, one being a surviving chantry priest, but the fifth named was absent. In the following year the rector was again absent; the curate of Newton, the former chantry priest, did not appear; but the curates of Ashton and Culcheth were present, and another is named. The improvement was only apparent, for in 1565 the rector, though present, non exhibuit, and only two other names are given in the Visitation List, and they are crossed out and two others written over them. It seems, therefore, that the working staff had been reduced to two—Andrew Rider and Thomas Collier. (fn. 75)

How the Reformation changes affected the parish does not appear, except from these fluctuations and reductions in the staff of clergy. The rector was not interfered with on the accession of Elizabeth; his dignity and age, as well as his family connexions, probably saved him from any compliance beyond employing a curate who would use the new services. His successor became a Douay missionary priest, suffering imprisonment and exile. Though the rector in 1590 was ‘a preacher’ he lived in Cheshire, and his curate was ‘no preacher’; nor were the two chapels at Newton and Ashton any better provided. (fn. 76) The list drawn up about 1610 shows that though the rector, an Irish dignitary, was ‘a preacher,’ the resident curate was not; while at the three chapels there were ‘seldom curates.’ (fn. 77)

The Commonwealth surveyors of 1650 were not quite satisfied with Mr. Herle, for though he was ‘an orthodox, godly, preaching minister,’ and one of the most prominent Presbyterians in England, he had not observed the day of humiliation recently appointed by the Parliament. They recommended the creation of four new parishes—the three ancient chapelries, and a new one at Lowton. (fn. 78) After the Restoration two or three meetings of Nonconformists seem to have been established. (fn. 79) In 1778 each of the four chapelries in the parish was served by a resident curate, paid chiefly by the rector, except Newton, paid by Mr. Legh. (fn. 80)

The great changes brought about by the coal mining and other industries in the neighbourhood have ecclesiastically, as in other respects, produced a revolution; and by the munificence of Rector J. J. Hornby—a just munificence, but rare—the modern parishes into which Winwick has been divided are well endowed.

There were two chantries in the parish church. The older of them was founded in the chapel of the Holy Trinity in 1330 by Gilbert de Haydock, for a fit and honest chaplain, who was to pray for the founder by name in every mass, and say the commendation with Placebo and Dirige, every day except on double feasts of nine lessons. The right of pre sentation was vested in the founder and his heirs, but after a three months’ vacancy it would lapse to the bishop. (fn. 81) A few of the names of the priests of this foundation occur in the Lichfield Registers, and others have been collected by Mr. Beamont from the Legh deeds. (fn. 82) In 1534 the income was 66s. 8d., and it remained the same till the confiscation in 1548. (fn. 83)

The second chantry, known as the Stanley chantry, was founded by the ancestors of the Earl of Derby. It was in the rector’s chapel, and endowed with burgages in Lichfield and Chester, bringing in a rent of 66s. 8d. (fn. 84)

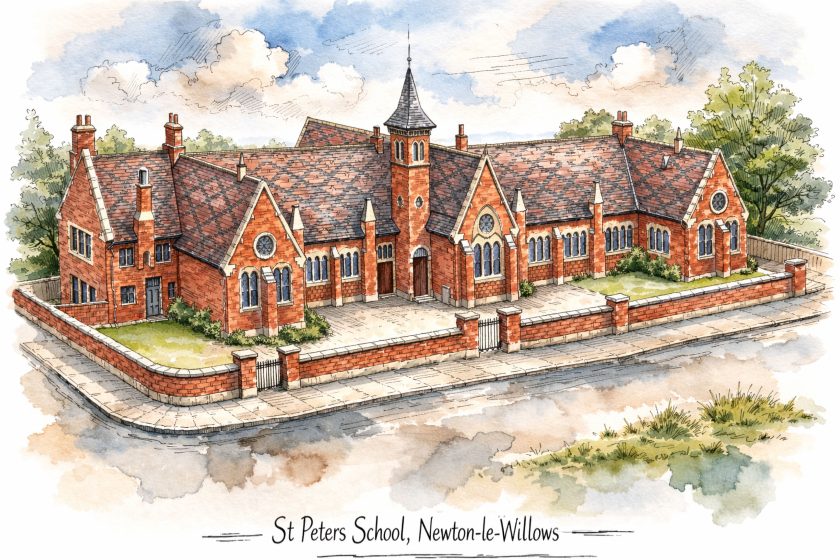

A grammar school, once of some note, was founded by Gowther Legh in the time of Henry VIII, and refounded in 1619 by Sir Peter Legh. (fn. 85)

CHARITIES

The charities of this parish are numerous and valuable. As in other cases, some are general, others applicable to particular objects or townships.

For the whole parish are the ancient bread charities and other gifts to the poor, (fn. 86) the Bible charity founded by Dean Finch, (fn. 87) and the modern educational funds. (fn. 88)

For Winwick-with-Hulme are gifts of linen, &c., for the poor, (fn. 89) and funds for binding apprentices, (fn. 90) and buying school books. (fn. 91) At Houghton, Middleton, and Arbury are poor’s cottages. (fn. 92) Golborne and Lowton together share in William Leadbeater’s benefaction. (fn. 93) The townships separately have some minor charities, (fn. 94) including poor’s cot tages at Lowton. (fn. 95) Newton had an ancient poor’s stock, spent in providing linen, and other benefactions. (fn. 96) A legacy by James Berry in 1836 has failed. (fn. 97)

For the township of Culcheth as a whole, most of the ancient charities have been united; (fn. 98) the Blue Boy Charity continues. (fn. 99) For Newchurch with Kenyon are funds for the poor, &c.; (fn. 100) at Risley the almshouse has failed, (fn. 101) but John Ashton’s Charity, founded in 1831, produces £31 10s. a year, distributed in money doles. (fn. 102)

At Southworth-with-Croft a calico dole is maintained. (fn. 103) Ashton in Makerfield has charities for linen, woollen, apprenticing boys, &c. (fn. 104) At Hay dock there are an ancient poor’s stock and a clothing endowment. (fn. 105)

‘The parish of Winwick: Introduction, church and charities’, in A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 4, ed. William Farrer, J Brownbill( London, 1911), British History Online [accessed 14 September 2024].