The following account was written in 1843 by the Rev. Edmund Sibson, once Curate at Winwick, and after- wards Vicar of St. Thomass, Ashton-in-Makerfield, and is entitled “An Account of the Opening of an Ancient Barrow called Castle Hill, near Newton-in-Makerfield, in the County of Lancaster”

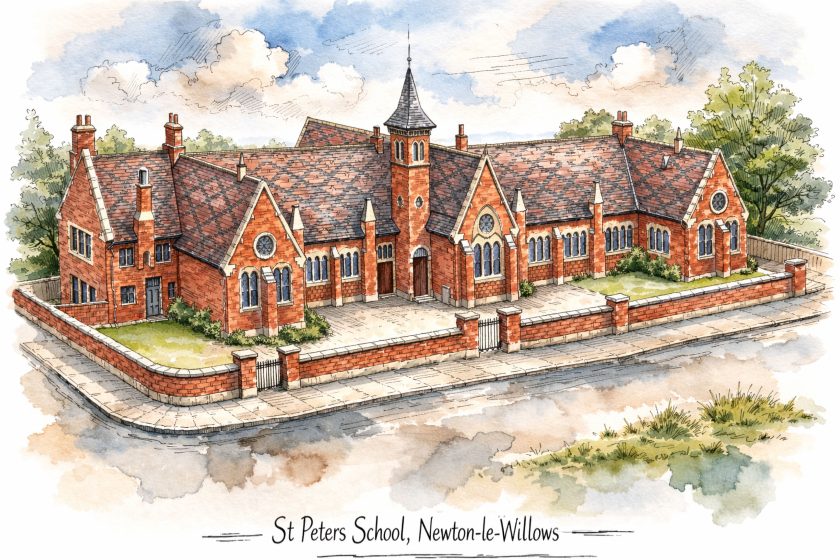

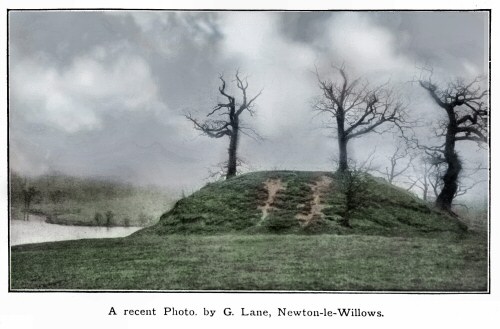

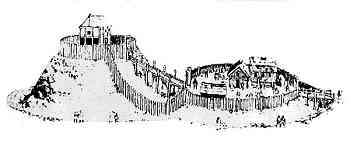

This Photo of Castle Hill is from the 1916, Vol II, History of Newton in Makerfield, by J H Lane.

edited and coloured from the original by Steven Dowd

Mr Bainess Description.

“At the distance of half a mile from and to the N. of Newton, stands an ancient barrow called Castle Hill. It is romantically situated on elevated ground, at the junction of two streams, whose united waters forms the brook which flows past the lower part of the town of Newton. The sides and summit of the barrow are covered with venerable oaks, which, to all appearance, have weathered the rude and wintry blasts of centuries. It is a spot well adapted for the repose of the ashes of the mighty dead. The barrow is about twenty-five yards in diameter and from eight to nine yards in height.”

The streams which unite at this barrow are the Dene and the Sankey.

British Road.

This barrow seems to stand near the old British road from the town of Haydock to the town of Lowton , both of which were probably British towns. This road runs from the town of Haydock , past Hall-meadow, down the Townfield-lane, and crossing the Wigan turnpike road near Newton it points to Castle Hill and the town of Lowton .

The Townfield-lane is six feet below the level of the adjoining ground, and is properly a British Covered Way ; and it is found that, where the Roman road from Warrington to Wigan crosses this old lane it slopes down to it on both sides thus plainly showing that the Townfield-lane was made before the Roman road. The British road seems to have crossed the Sankey, close to Castle Hill, where two piers have been erected for a bridge.

Robin Hoods Cave.

At this ford of the Sankey there is a cavern, in the red rock, which is called Robin Hoods Cave.

Form of Castle Hill.

This barrow is bell-shaped, like those on Salisbury Plain; and its circumference is nearly circular. Its circumference at the bottom is 320 feet; at the top 226 feet; and its height is 17 feet.

On the south and west sides of Castle Hill there is a large fosse about 5 feet deep and 30 feet wide. This fosse appears to have been originally 7 feet deep, 2 feet of which have been cut in the rock; but on the other sides there is no fosse; for the ground slopes towards the Sankey and the Dene.

The foundation of the barrow has been upon the original greensward; and the barrow has been formed by the earth and rock taken out of the fosse. There is a tradition that Alfred the Great was buried here, with a crown of gold, in a silver coffin. The barrow had long been an object of curiosity, and, for more than twenty years, there had been a general wish to explore it.

Opening of the Barrow

At length, with the consent of Thomas Legh, of Lyme, Esq., the Lord of the Manor of Newton, a number of colliers were employed by the Rev. Peter Legh, M.A., the Incumbent of Newton; Edward Holme, of Manchester, M.D.; Mr. William Mercer, of Newton, agent to Thomas Legh, Esq.; and the Rev. E. Sibson; and excavations were made in this barrow on July 6th, 7th, l0th, 1lth, and 14th, 1843.

Gentlemen resent at the opening

The principal part of the barrow was explored on Friday, the 7th of July, in the presence of the Rev. Peter Legh ; E. Holme, of Manchester, M.D. ; John Roby, Esq., M.R.S.L., author of the Traditions of Lancashire ; William Langton, Esq., of Manchester, a descendant of the ancient family of that name, formerly barons of Newton ; James Dearden, Esq., lord of the Manor, of Rochdale ; James Fenton, Esq., of Lymm Hall; Joseph Fenton, Esq., of Bamford Hall ; W. Beamont, Esq., of Warrington ; John Robson, Esq., of Warrington, editor of Three Metrical Romances, from the Blackburne MSS.; John Green, M.D., of Newton ; Samuel Ashton, Esq., of Bury ; John Bimson, Esq., of Wigan ; John Sharp, Esq., of Warrington ; James Allen, Esq., of Newton ; Arthur Potts, Esq., of Newton, and most of the gentlemen in the neighbourhood.

It was expected that a Kistvaen [ i.e., a prehistoric grave, oblong, and composed of four or more uncemented slabs forming its sides, and covered with a great stone ] would be found, containing amber and glass beads, ornaments of bone, and a Celt [ i.e., a stone or bronze axe ]. It was also supposed that the Kistvaen would be on the level of the original green-sward; and at this level, about to feet below the top of the hill, an opening, 4 feet square, was made in the west side of the hill; and this opening was driven forward horizontally towards the centre of the hill, till it met a shaft, 6 feet in diameter, which was sunk from the centre of the top of the hill. This work was done by nine colliers, brought by Mr. Mercer from Haydock. They began to work a little after noon on the 6th of July; and they laboured day and night, without intermission, with persevering energy and hearty good-will, until nine oclock in the evening of the following day.

Drift at the West Side

The hill was found to be composed of clay and marl, red sand, and red sandstone; but the west side of the barrow was composed principally of stiff red clay.

Burnt Clay and Charcoal

In the drift, on the west side of the hill, nearly on the level with the original sward, were found patches of burnt clay and marl, mixed with ashes and pieces of wood-charcoal. The ashes seemed to be coal ashes, for a piece of unburnt coal was found in the clay; and this proves that the use of coal was not unknown when this barrow was made. Several stones were found on which there were evident marks of the action of fire. The pieces of wood-charcoal were very light: the fibre of the wood was very visible; and we should have thought that the wood had been beech if Caesar had not said that there were no beech trees in Britain . A cubical piece of this wood-charcoal, nearly three inches square, is in the possession of the Rev. Peter Legh.

Oak Branches

Roots and branches of oak were found embedded in the marl in this drift: the bark remained entire, and retained its original form and colour, but the wood was entirely absorbed and the space, once occupied by the wood, was now filled with the fine aluminous red clay, of which the barrow was partially composed. It was thought by Dr. Black, of Manchester , that these branches of oak were in a state of transition from vegetables to fossils; and that, in some two thousand years more, this aluminous clay would have become stone, and the bark would have been carbonized. In Fossil Wood, however, the fibres and grain of the wood are visible; but iii this aluminous clay no trace of the wood was visible.

Perpendicular Shaft and Anticipated Deposit

Most of the things found in the shaft were similar to these discovered in the western drift. In sinking the shaft, however, from the top of the hill, it was observed by Mr. Mercer that, on the north side, the earth was loose sand, but that, on the south side, the earth was a compact body of clay and marl; and it was therefore thought by Mr. Mercer that the deposit contained in this barrow would be found under the coats of marl on the south side of the shaft. Mr. Mercer also observed that there was a short circular ridge on the south side of the top of the barrow.

The position of the original greensward was easily seen in the shaft, for there was almost a perfect ring of tufts of decayed grass round the shaft: these tufts of grass had the appearance of compressed hay, the blades of grass being long and strong. Below the grass were seen the natural strata of earth, clay, and marl. Two feet below the ring of grass a large living black beetle was found.

Drift from the Shaft to the South Side

At the suggestion of Mr. Mercer, a tunnel, 3 feet square, was driven horizontally on the level of the original green-sward, from the shaft, into the south side of the barrow.

Chamber

And at the distance of about ten feet from the centre of the barrow, on the south side of the shaft, a chamber was discovered, which, it is supposed, contained the original deposit. The base of this chamber was 2 feet broad, and was curved; its length was 21 feet; its height was 2 feet; and its roof was a semicircular arch. It seemed to be constructed of masses of clay about a foot in diameter, rolled into form, in a moist state, and closely compacted by pressure. When the chamber was first opened the candles were extinguished, and there was great difficulty in breathing. The sides and bottom of the chamber were coated with an impalpable powder of a smoke colour.

Animal Matter

The bottom of this chamber was covered with a dark-coloured substance about three inches in thickness. The external surface of this substance was like peat earth, being rough and uneven and of a black colour. The inside of it, when broken, was close and compact and somewhat similar to black sealing-wax, and, when examined by the microscope, it was found to be closely dotted with particles of lime. And it was thought to be a mixture of wood ashes, half-burned animal matter, and calcined bones.

Beetles

An immense number of the elytra ( *1 ) of small beetles were found embedded in this cake of carbonized animal matter. The elytra were of a light puce colour about a quarter of an inch in length. They were striated longitudinally, and, in the channels, were spherical dots, which, when examined by the microscope, had a very beautiful appearance. It was thought that these insects belonged to an extinct species which had its existence when the temperature of the earth was higher than it is at present. But Mr. Westwood, of Hammersmith, an eminent entomologist, says that these beetles are of the species Cossonas, and are of a genus of wood-boring beetles; and that the species is not extinct; and that he has specimens of the same kind both from Greece and Egypt .

( *1 ) Elytra, or “sheaths,” the name given to the anterior wings of beetles, which are converted into hardened wing-covers, having for their object the protection of the delicate gauzy wings beneath. The elytra in beetles are often beautifully marked and sculptured.?Harmsworths Encyclopedia.

Trench

This plate of animal matter seemed to have been placed on the level of the original greensward. And on the surface of this animal matter was a covering of loose earth, about two inches in thickness, which seemed to have fallen from the roof and sides of the chamber. Immediately below this plate of animal matter a trench had been cut about fifteen inches in depth; and two tiers of round oak timber had been placed in the trench. The first tier was notched into the greensward; the second tier was nine inches below it. The horizontal distance of the several pieces was about eighteen inches; and the pieces in the lower tier were placed exactly opposite to those in the upper one. Several of the pieces were charred; and many of them had entirely disappeared, leaving black marks in the side of the trench, where they had formerly been placed. These pieces of oak appeared to have been three or four inches in diameter. In almost all the cases, the wood of these pieces had been absorbed: in some cases the bark, on the under side of these pieces, was carbonized, and had nearly the appearance of coal; and in other cases the bark, on the under side of these pieces, retained its original form and colour. In one case, how-ever, one of these pieces, in contact with the animal matter, had the appearance of dry, decayed wood. This piece of wood is in the possession of Mr. John Robson, of Warrington .

The trench below the plate of animal matter was filled with clay. The oak being sacred to the Druids, it is probable that the trench was made for the purpose of containing the tiers of oak, so that the bodies might rest upon sacred wood.

There was no appearance of either Kistvaen or urn; and neither armour nor ornaments were found. From this it may be inferred that the barrow had been made in a very rude state of society, when the arts were in their infancy.

This chamber containing the animal matter appeared to have been airtight; for its exact termination was discovered on the west side; and it was found to be closely sealed up with bundles of grass, a coat of ferns, dry roots, and clay. The ferns and the roots were placed against a vertical face of clay, on the outside of the chamber; and they were not carbonized.

It seems probable that the bodies had been partially burned, with wood and coal, on the greensward, on which the barrow was formed: that the partially burned remains of the bodies had been carefully collected and deposited on the surface of the circular trench; and that then a wall and a strong arch of moist clay had been formed over these remains. It would be necessary that this arch and chamber of moist clay should become hard before the barrow was formed, otherwise the weight of the barrow would compress and destroy the chamber. Therefore that the arch and chamber might be hardened by the suns heat on the outside, and by the heat of the half-burned remains on the inside, it would be necessary that the two ends of the chamber should remain open for a considerable time before the barrow was raised. And it is probable that, when the half-burned remains were cool, and while the two ends of the chamber were open, the beetles would creep in and burrow in the animal matter. And when the arch and sides of the cavity became hard and solid, the two ends of the chamber would be closed, and the barrow would then be raised. After the ends of the chamber were closed, the half-burned animal matter would gradually become hard, and the beetles embedded in it would die.

Pieces of the carbonized animal matter are in possession of nearly all the gentlemen who were present at the opening of the hill.

It is probable that this chamber contained the original deposit, and that it had never been opened before.

Deveral Barrow

When the Deverel Barrow, in Dorsetshire, was opened by Mr. Miles in 1825, it was found that the bodies had been burned: that most of the ashes had been protected by urns; that the urns were disposed in a circular form; that the most ancient urns were moulded by the hand, without the assistance of the potters wheel: that these urns were made of earth which had not been baked, but only dried in the sun; and that, in this barrow, urns were found of better workmanship, evidently made upon a potters wheel, in a more advanced state of society; which showed that the barrow had been used as a place of burial for a long period. Mr Miles, in his account of the Deverel Barrow, says: ” All the urns, except one, were placed with their mouths upwards, which appears a custom more prevalent in Dorset than in Wiltshire barrows; since Sir R. C. Hoare, in his introduction to ` Ancient Wilts, observes that the bones when burned were collected and placed within the urn, which was frequently deposited with its mouth downward, in a cist cut out of the chalk.”

The circular chamber at Castle Hill corresponds to the circular base on which the urns were placed in the Deverel Barrow: the animal remains, placed on the greensward, and the arch of clay above them, correspond to the inverted urns, covering the ashes, described by Sir R. C. Hoare in the Wiltshire harrows; only the arch of clay at Castle Hill seems to indicate a more ancient period than the inverted urns iii the Wiltshire barrows. The arch of clay at Castle Hill seems to correspond with the passage in the Book of Job, chap. xxi. 32, 33, ” Yet shall he be brought to the grave, and shall remain in the tomb. The clods of the valley shall be sweet unto him.”

As neither urns, nor Celts, nor armour of any kind, nor beads nor ornaments were found in this chamber, it would appear that this barrow at Castle Hill is of very remote antiquity.

Probable Age of the Barrow

In the Rev. Mr. Whitakers History of Manchester, vol. i.; pp. 7, 8, we are informed that a colony of Celts settled in Lancashire 500 years before the Christian era ; and that, about 150 years afterwards, this country was invaded by the Be1ga:. As the barrow at Castle Hill seems to be one of the most ancient, it is probable that some of the kings of the Celts, having been defeated and slain by the Belgae, were burned at Castle Hill 2,193 years ago.

Acorn

An acorn was found in the chamber on the plate of animal matter. The plumula and the radicle were in a state of complete germination; though it is probable that this acorn had lain undisturbed in this cavity for nearly 2,200 years. Both the plumula and the radicle were of a white colour; and the radicle was twisted in a spiral form.

This acorn is in the possession of Mr. Mercer, of Newton . An acorn, in a similar state of vegetation, was found in 1810 by the Rev. William Marriott, in a harrow at Ludworth; and it is described by him in his History of the Antiquities of Lyme.

Impression of a Human Body

On the roof of the east side of the chamber, Mr. Mercer discovered a very distinct and remarkable impression of a human body. There was the cavity formed by the back of the head; and this cavity was coated with d very thin shell of carbonized matter. The depression of the back of the neck, the projection of the shoulders, the elevation of the spine, and the protuberance of the posteriors were distinctly visible. The body had been that of an adult; and its head lay towards the west.

Position of the Chamber

There seems something remarkable in the position of the circular chamber in which the animal matter was found. If the circular arc of this cavity be bisected, the bisecting line will point nearly to the position of the sun at three oclock in the afternoon; and, therefore, this time will nearly indicate that time of the day, at the summer solstice, when the heat of the sun is greatest, and when, therefore, it would be supposed the suns influence was greatest. Now, Mr. Whitaker, in his History of Manchester, vol. ii, pp. 182, 184, informs us that the Druids were astronomers, and that the sun was worshipped in Britain . It seems, therefore, that in the construction of the circular chamber at Castle Hill particular regard had been paid to the suns influence.

Ridge on the Crest of the Hill

It is also remarkable that the exact form and vertical position of the circular chamber is indicated by a ridge on the crest of the hill. This was first noticed by Mr. Mercer, and this was also an additional reason why the tunnel was driven from the bottom of the shaft towards the south.

As these harrows were burial-places for persons of distinction until about the year 750, when the custom of interment in churchyards was brought over from Rome into England by Cuthbert, archbishop of Canterbury, it is probable that many pilgrimages were made to this shrine of relics, and that devotees knelt and wept on the top of this barrow and struck their foreheads on this sacred ridge.

It is also known that religious festivals were observed at these barrows; and it is probable that venerable and hoary Druids preached, from the summit of Castle Hill, to listening multitudes.

Excavations in the Hill

In attempting to make further discoveries at Castle Hill, the shaft was sunk down to the rock, which was found at the distance of about eighteen feet from the top of the hill; and it was discovered that the surface of the rock was about four feet higher in the centre of the hill than in the centre of the fosse, on the west side of the hill. In sinking this shaft nothing was found but the black beetle already mentioned, and a small piece of wood-charcoal.

Three shafts were also sunk in the circular chamber, containing the animal matter. These shafts were sunk into the undisturbed strata of solid earth, nearly to the rock; and nothing was found except the trench and the two tiers of oak wood already described.

Drift on the East Side

The drift on the west side of the hill was continued in a straight line, through the hill, to the east side ; and on the east side of the centre of the barrow the earth was less compact, and was mixed with sand and large fragments of red freestone.

Whetstone

In this drift, on the east side of the shaft, and near the centre of the hill, a broken whetstone was found. It was of freestone, of a fine grain, of a dull white colour, slightly veined with red; and the surface was finely polished. It was about five inches in length and three in breadth. There is no stone like it in this neighbourhood. This whetstone evidently be-longed to a much later period than that of the circular chamber in which the remains of animal matter were deposited. The whetstone is in the possession of the Rev. Peter Legh.

Drift on the North Side

On the north side of the barrow, about six feet above the bottom, a drift four feet square was carried horizontally about eleven feet towards the centre of the hill; and because the ground on the north side of the hill slopes towards the Dene, this drift was commenced at a lower level than that on the west side. It was found that the hill on this side was formed of clay and red sandstone.

Fragment of an Urn

Nothing was found in making this drift; but when the workmen were filling up the drift a fragment of unglazed pottery was found in the clay. It was made of fine cream-coloured potters clay, which was very soft and flexible, when the fragment was first found; but which soon became hard by exposure to the air. It had been made on a potters wheel; for there were exactly circular marks on its surface. It did not seem to have been baked in an oven; but its surface seemed blackened and discoloured by fire. It had not been broken lately, for the edges of the fracture were dull and discoloured. It seemed to have been part of an urn, whose diameter was about eight inches. This piece of pottery is in the possession of the Rev. Peter Legh.

As the first burials in this hill were made tinder a rude arch of clay; and as this piece of pottery seems to have been a fragment of a funeral urn, made of fine clay, and highly finished in an advanced state of the arts on a potters wheel, there must have been a long interval between the time when the original deposit was made in the chamber and the time when this urn was made. And from this it appears that Castle Hill had been a place of interment for persons of distinction for a long period. And as only a fragment of this urn was found, it is evident that a part of the barrow had been previously explored.

Oaks

There are now ten oaks on the top of Castle Hill: they may be 300 years old; and they probably were planted by the Langtons when they were barons of Newton . And when the oaks were planted a search would probably he made for antiquities, and the urns might then be found.

White Lady of Castle Hill

It is scarcely necessary to add that Castle Hill is said to he haunted by a White Lady, who flits and glides, but never walks ; who is sometimes seen at midnight, but never talks. She was probably, like Sir Walter Scotts White Lady of Avenel, “when there stood the figure of a female clothed in white, within three steps of Halbert Glendinning.”

“I guess twas frightful there to see

A lady richly clad as she

Beautiful exceedingly”

Waverly Novels -” The Monastery”

Copper Coin

We were not a little puzzled by the trick of an artful boy, from Newton , who contrived to thrust an old halfpenny into a piece of clay, at the bottom of our excavations. The halfpenny had been in the fire, was much corroded with rust, and the impression was very indistinct; but it was found to be a coin of George II. If this little trick had not been discovered, we must have inferred that the barrow had been opened before.

As the Rev. Peter Legh had given an invitation to his friends to be present at the opening of Castle Hill, on Friday, the 7th of July, we soon found that it would be necessary for the colliers to work all night, so that the openings might be ready. During the short twilight of a summers night, there was a sharp, cold breeze on Castle Hill; and we kindled a fire on the top of the hill. The eddying columns of white smoke rising under the lofty arch of oak boughs ; the breezes veering and whirling two or three times round from every point of the compass ; the flickering flame throwing its glare of light upon the quivering arch of oak leaves ; the dark and dingy faces of the colliers standing close about the fire ; and the apprehension that the White Lady of Castle Hill might be looking upon our rash proceedings with displeasure, produced an association of ideas not easily to be expressed.

Such was the Rev. Edmund Sibsons minute and interesting account of the opening of Castle Hill.

The learned author of the article on ” Ancient Earthworks,” in the ” Victoria History of the Counties of England,” a work now in course of publication, writes thus of Castle Hill :-

From its top the Castle Hill effectively commands the whole of its immediate surroundings; it also overlooks the level ground on the farther side of the river valleys. There is no adjacent bailey [the court or space enclosed within the external walls of a castle] now traceable; it is possible, however, that there may formerly have been one in part of the slightly elevated field to the south, which has been altered by much ploughing; an old inhabitant still remembers the existence of ditches and banks here.

This Castle Hill, like many another in the district, has been described as a sepulchral barrow, and also as a Roman botontinus; but the position in which it is placed, and the excavations recorded, distinctly point to its being a defensive earthwork of the class we are now considering; and this notwithstanding the curious interment found below it.

History, unfortunately, has no account to give of the origin of this castle. Newton was the seat of a barony, of which the mount was very probably the site, even if it was not the spot where the – earlier ?kings house” of Edward the Confessors time, mentioned in Domesday, stood.

The ten oaks, 300 years old, mentioned by Mr. Sibson as growing on the hill in 1843, have long since disappeared, as have also many in the adjoining little wood. There is now one oak in a flourishing condition, probably a descendant of one of the ten, and a white hawthorn bush, growing upon the hill ; and on its sides the hundred rhododendrons planted four years ago are making a brave struggle for existence in a somewhat barren soil tunneled with rabbit burrows.

The Road to Castle Hill.

This road from Church-street across the fields and over the lake by the bridge to Golborne Hall was constructed about the time the lake was made, the original road or path in that direction running by the cottage occupied by Mr. C. Watson, the parish clerk, alongside the field where now are the glass-houses of the kitchen-gardens belonging to “The Willows,” and thence by the north-western bank of the valley, in which valley, opposite to the hill, were a ford over the brook and a road to the hall. Shortly after the lake was formed, the path thereto ran alongside the hedge in the next field, and remained there until the spring of 1908, when it was obliterated by the plough.

On the right of the present road, in a line with the Vicarage, stood the gaunt, whitewashed, three-storied house known as “Ellams,” behind which, on the site of the little cemetery, were farm buildings, Ricks, a small orchard, and a little pit. The house on the left, now known as “Kirkby” was erected in our time, and is worthy of note as being the birthplace and headquarters of the South Lancashire Division of the Needlework Guild, which guild was founded by the late Giana, Lady Wolverton in 1882. This division or branch of the guild was established, in 1888, by Mrs. Clare Royse, a lady very active in promoting entertainments in aid of charitable objects. The first president of the division was Lady Wolverton, who held the position till her death in 1891, when Her Majesty Queen Mary, then Duchess of York, graciously consented to act as president, and has never failed to send her contribution of garments “always up to time and most generally made by herself.” On Mrs. Royses retirement owing to leaving the district, Miss C. I. Watkins, who had been an active vice-president from the commencement, was appointed secretary, and under her management the division has maintained its large number of vice-presidents and associates, and has done much good in providing institutions for the sick and needy with articles of clothing, no fewer than 61,414 garments having been collected and distributed during the twenty-five years of its existence. The division, according to the 1913 report, numbers 33 vice-presidents and 753 associates.

Passing along this road, we soon obtain a view of the lake and the hill. The land on our right, from this point to the hill, was formerly divided by hedges and ditches into four fields, and on our left were eight other fields similarly divided. The hedges have been removed and the ditches filled in, thus giving additional land for cultivation and also saving the farmer the cost of hedging and ditching ; but now, in our summer walks along this road, we miss the pleasures of long ago?the song of thrush and linnet and the scent of hawthorn and honeysuckle in the hedgerows, and the gleam of foxglove, hyacinth, and harebell on the banks below.

Notes on Castle Hill by Peter. Mayor. Campbell

The Dene,

The local pronunciation deighn gives a clue to the primary meaning of the name ” Dene,” which is old German Denju (where the “j ” is a palatal sound), and means “to make thin, to make small or slender, diminish, lessen, attenuate,” a characteristic of tine stream in this valley, and not inconsistent with its secondary gleaning in vol. i., p. toy.

The Sankey

Sankey” is the form in which Sanga, ae, a river in Cantabria in Spain, citeriore, has come clown to us in Lancashire. Sange, ae, is mentioned by Pliny, I. 4, c. 20, and also by Terence in “The Eunuch “?the tennis ” k ” taking the place of the media both momentary sounds, while the a, diphthong, become ,b, all in phonetic sequence. The name is derived from San,,jaa, another form of Sauce.,, ci, the name of Hercules in the Sabine language, from which Propertius quotes in fin. el 9, t, 4. This raises a question whether it came with the Spanish Legionaries under Hadrian or with Italians direct from Herculaneum under the Emperor Vespasian, for the eruption of Vesuvius, in A.D. 79, annihilated the town of Herculaneum, which derived its name from the worship of Hercules peculiar to the place, and is said to have been founded by the hero himself, during his wanderings in the West. It was inhabited by Oscans, the aboriginal natives of the country, by Tyrrhenians, and by Samnites before it became subject to Route. There was a Sabine province, part of East Umbria, in the Abruzzi , and the Romans overcame the Sabines, in the Sabine War, in the time of Romulus and Tatius ; and, as was their custom, impressed them into their foreign service, either in Spain or in Britain . On account of its salubrious situation, on a height, between two rivers and near the sea with the harbour of Resina , it because a favourite site for Roman villas. It retained its name even after the second eruption in A.D. 472, fifty years after the Romans retired from Britain . It may have come any time after the Sabine War. Vespasian was in York in A.D. 77. Hadrian also was in York , coining direct from Spain (the Iberian Peninsula ). Hadrians Wall was built by command of Adrian, who visited Britain in A.D. 120. In any case, the river was named in honour of Hercules, and, we must suppose, with all the rites and ceremonies of that cult, though Varro relates that for 170 years the Romans honoured their gods without statues. He adds that if they had preserved that custom the cult of the gods would have been very pure and very holy. However that may he, we know that the ensigns became an object of cult to the soldiers, and that the Sabines had a “sacrificial religion.” As the Roman legions were all recruited from the same places where they were first raised, as long as they were in any given locality, we know the men were of the same nationality, whether Romans, Iberians, Germans, or Lithuanians, as signified in the various Imperial titles. The Piktas, f, ta /base, not Latin pictus, “painted,” nor pictari (from Aquitania ), but, as the name signifies, “bad ones,” were Lithuanians. They left the name “kid cote,” Kudas Kutas (small debtors prison), on Old Ouse Bridge its York, and in Lancaster on the Lune, with a few other words, such as Warter on the Yorkshire Wolds– vartai, pl., for, “a tower” ; or Wartai, m. pl., porta cohortaliss, a narrow pass, pass, passage, defile in possession of a cohort,” a band of soldiers consisting of three manipuli or six centuries, the tenth part of a legion.

They revolted in York , and Severus came to suppress them, and remained to Triumph. his wife Julia Domna was a votaress of Baal, and gave name to one of the gates of the city of York, the Great Lady Gate, or ,Bon-dom Bar (” Dom” is a contraction of Domua or Domino, with the Greek prefix Bou : the present name ” Bootham” obscures its history), so named by Leland, King Henry VIII.s antiquary, in his “Itinerary,” for Roman officers spoke both Latin and Greek, as ours speak English and French (see note on worship of Baal in vol. i., p. 149(.

The cohors was an inclosure of wood, hence the name “cohort,” and the nucleus of the old town on the Dene, originally a resort of the Druids to the There-oak, for the name on one of the Estate plans is “Theroke Dene,” which is evidence that the Druids (L. Druidae, Gr. deus, L. robur) spoke Greek as well as Keltic, though they wrote neither, for all their ritual was oral and aural. (Ther-a, dress worn on festivals of Bacchus. The dresses were made in the isle of Thera.) Moreover, we see that it was, as the name “porta” also means ” on the boundary,” as the Castle Hill?Castle, castellum, “a castle fortress, fort, fortified place, small fortress” ; Hill, mons, collis, tumulus, “a little hill or mound.” But we shall look in vain for any castle in the modern sense. It was, to quote ?Veget. I. 3, de re milit., c. 7, in f?, “locus militari opere munitas exstructo aggere, vel muro cum , fossa, quasi parcum castrum, ut est apud quia in eo milites pouuntur ad custodiam regionis,” “a military work for the protection and defense of the district in which it is placed, with all the requisite men and appliances to make it secure against attack.”

Besides, the names they gave to things and places were all during the Roman occupation, whereas the Keltic names were of an earlier date. This word “Sankey” had been a puzzle to me nearly all my days, the nearest approach to it being Sanke, in Norman French, pronounced “sank,” from Latin Sanguen, “blood,” with ey, “a watery place.” It may be useful to remark that Bou had been adopted with the spelling “Boo,” by the Latin, as well as Thera in the word Therapneus, a Sabine word from the Greek.

Townfield Lane

After the land was drained, Townfield Lane was known as “Watery-lane,” and in the course of time became impassable even for pedestrians. The Allotments were on the right-hand side from the Newton end, as shown on the Ordnance Survey Map of 1843. A vestige of the fosse-way across the moor led past the old school. It was for years a favourite haunt of mine for nutting, and I traversed a portion of it almost daily when a boy in going to the Tilery with dinners.

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great died in 901 and was buried at Winchester , but his bones were dug up in order to build a jail, which was condemned as insanitary, for it was the site of a burial ground.?See ” Liber Monasterii de Hyda,” Appendix, 1868.

No Beech Trees in Britain

An historical error. Sherwood Forest of our day is a beechwood, whatever it was in Robin Hoods time. Earl Manverss oaks are one thousand years old and hoary with age.

Roman Botontinus

Botontinus, Botones, Botontini, and Bet on-tones or Bodones, “boundaries of land “?an agrarian term very seldom used.?Faust et Val. (” Monticellos plantavimus de terra”), quos botontinos appellavit. This would apply to the Castle Hill. Greek, Bo-ton “shepherd, herdsman, feeder, and flock, herd, cattle,” with Tina “I value, esteem, reverence, honour, pay a penalty, expiate, atone for, requite;? Mid., “I exact payment, avenge.”

The Rev. Edmund Sibson

The Historian of the Hill, had resided in Ashton-in-Makerfield for about forty years, and was the minister of that part of the extensive parish of Winwick before it was divided and constituted a vicarage some few years since. He was a fine specimen of a true Englishman, and possessed high and varied intellectual attainments, united with extraordinary goodness of heart and simplicity of manners. A native of the north of England , he cause to Ashton as the incumbent. At the time of his coining, and for many years afterwards, the curacy possessed by no means an ample stipend, and Mr. Sibson made up its deficiency by taking pupils. All who were educated by him must ever hear a sincere respect for his memory. After a residence of nearly forty years in his parish, few clergymen have left so honoured a memory amongst all classes of his parishioners, whether rich or poor. To the former he was a kind neighbour, easy of approach, and ever ready to give his advice and to arrange any difference that might arise amongst then). To the latter he not only cared for their spiritual welfare, but his hand was ever ready to relieve their distress; and he not only faithfully discharged the duties of their pastor, but was at once the doctor and lawyer of his poor parishioners, for whom he gratuitously prescribed and whom he advised. Not content with the sphere of his parochial goodness and usefulness, this worthy man cultivated, with success, several branches of science. For many years he collected the geological facts of his neighbourhood, and had become possessed of a good local collection of the fossils of the district in which he lived. But it is by his valuable contributions in mathematics (in which science he stood very high), and in antiquities, that he is best known to the public. In vol. v. (new series) of the “Memoirs of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester,” is a paper contributed by him in the year 1824, entitled “An Investigation of the Curve of Quickest Ascent.” The illustrious Newton has ascertained the curve of quickest descent; Mr. Sibson, in his paper, solved the problem of quickest ascent. In vol. vii., of the same memoirs, Mr. Sibson contributed two papers on antiquarian, and one on mathematical, subjects. The first was “An Account of the Opening of an Ancient Barrow, called Castle Hill, near Newton-in-Makerfield , in the County of Lancaster .” The second was a paper “On the Pressure of Steam which caused the Explosion of the Boiler of the Irk Locomotive Engine at the Manchester and Leeds Railway Works, Miles Platting, on the 30th day of January, iS45.” The last communication was an account of a Roman public way from Manchester to Wigan .

Although about sixty-six years of age, up to within the last month Mr. Sibson possessed a robust frame and constitution, into which time had apparently made but few inroads. His mind was as active and deter-mined as it had ever been, and, to all appearance, many years of his useful life might yet be expected to be spared for the benefit of society; but it has been destined otherwise. Anxious to pay his respect to the memory of the late Edward Holme, M.D., F.L.S., the president of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, Mr. Sibson, who was an honorary member of the society, came over to Manchester to attend that gentlemans funeral. During the ceremony, owing to the wetness of the weather, he took a severe cold, which terminated in an inflammation of the lungs, and has closed his life on Wednesday evening last. Mr. Sibson had been married many years, and has left a widow and an only daughter. Doubtless the society of which he was so valuable a member will show some mark of respect to his memory Contributed to the Manchester Guardian of Wednesday, December 29th, 1S47. Mr. Sibson was buried in St. Thomas s Churchyard, .Ashton-in-Makerfield, and on the north side of the chancel of the church a tablet, with this inscription, is erected to his memory: “Sacred to the Memory of the Revd. Edmund Sibson, Minister, and First Vicar of this Parish for a period of 38 years, who died at Ashton, December 2znd, mS47, in the 66th year of his age.” He was a valued friend of Mr. William Beamont, with whom he associated in local antiquarian research, and the latter, in the introduction to his book, ” Warrington in MCCCC.LXV” pays a graceful tribute to the memory of his reverend and talented colleague.

Whilst Curate at Winwick, and also during his sojourn at Ashton, his portly figure was often seen at Newton, and we have heard him described by an old Newtonian as a tall man of athletic build, who walked with a swinging gait, his bead erect, his right arm swinging at his side, and his left arm placed behind him.

Finally (to quote Mr. Beamont), he was one “whose high reputation as a man of letters, an antiquary, and a mathematician, was his least recommendation, and whose consistent discharge of the relative and social duties, and, above all, whose unwearied zeal in the performance of the duty of his high office as a Christian minister, demand, to describe them justly, a language which would sound like adulation.”

Thomas Legh, Esq

The Lord of the Manor, by whose consent the Hill was opened, was born in the year 1792. and died on Friday, May 8th, 1S57, at Milford Lodge, Lymington, Hants. Although for many years past, in consequence of indifferent health, Mr. Legh took no very active part in national or county affairs, yet in early life he was known as a distinguished traveller, a successful investigator of classical antiquities, and an explorer of the mysteries of early Egyptian civilization. For all these his vigorous, well-knit frame, his bold and daring spirit of adventure, and fine classical attainments eminently fitted him. Left when very young the inheritor of a large estate, he no sooner finished his curriculum at Oxford than he prepared to gratify his fondness for travel and his love of adventure by a voyage to Greece and Albania, whence he extended his researches to Egypt and Nubia, as far south as Ibrim. Leaving England in 1S12, when scarcely 20 years of age, he sailed for the Egean, and visited, in company with his friend, the Rev. C. Smelt, the Islands of the Archipelago. After three months spent among these islands, he landed on the eastern side of the Isthmus of Corinth, and from the south side sailed down the Gulf of Lepanto to Zante, “where he had the pleasure to witness the arrival of those celebrated friezes that had recently been discovered in the temple of Apollo , at Phigaleia.”

In the excavation and removal of the beautiful sculptures composing this frieze, now one of the chief ornaments of the British Museum , Mr. Legh was largely instrumental both by his purse and his active personal exertions. A complete set of casts of these sculptures (presented to him, we believe, by the Government of the day) now adorn the corridor of his mansion at Lyme. Passing over to Egypt , he ascended the Nile with a determination to penetrate into Nubia . The only European traveller, who had previously succeeded in entering Nubia , namely, Norden, had been stopped at Dehr, and the difficulties of traversing the country had hitherto been deemed insurmountable. Mr. Legh and his companion, however, reached Ibrim, considerably further south, and here the scarcity of provisions, the cessation of monumental antiquities, the objects of their explorations, and the fear of falling into the hands of the Mamelukes, whose vindictive hatred had been excited by the oppression and cruelties of Mehemet Ali, induced their return; and after some singular and dangerous adventures they reached England in November, 1813.

Mr. Legh subsequently published an account of his journey under the title of ” A Narrative of a Journey in Egypt and the Country beyond the Cataracts,” “a work,” says Dibden, “which displays the enterprise of a veracious traveller and a perspicuous and modest writer, and which should be read by every one in whose breast the mention of the river Nile produces something approaching to a convulsive throb.” Finding himself at Brussels on the eve of the Battle of Waterloo, Mr. Legh offered himself as a volunteer, and served as an extra aide-de-camp to the Duke of Wellington (luring the whole of that memorable combat. Afterwards he visited Arabia Petraee, and was the first Englishman who surveyed the ruins of Petra . He traversed, at different times, nearly all parts of the civilized world, residing much in the East. His great delight, however, was his yacht, in which, with plenty of sea-room, he cared for nothing. From 1819 to 1831 Mr. Legh represented his own borough of Newton in Parliament.

The various treasures of art and antiquity that he had collected in his travels he deposited, with some few exceptions, in his fine ancestral mansion at Lyme, one of the noblest edifices in England, which in its pictures, exquisite carvings, and furniture, can scarcely be surpassed. With a rare liberality, whether he was at home or otherwise, he allowed the house to be at all times open for inspection, never permitting anyone to be sent away. His park?interesting for its wild scenery and its herds of wild cattle and of red fallow deer?was also always open to the recreation of the people of his neighbourhood. Indeed, his greatest pleasure was to see other people enjoy themselves, with which enjoyment he rarely allowed his own convenience to interfere Mr. Legh had a commanding figure and a noble presence. His countenance, eminently handsome and dignified, had yet such an urbane, kind, and genial expression, that he won all who were brought into contact with him ; whilst, to his intimate friends, he was at all times so cordial and gentle that he secured their affectionate regard and esteem to an extent attained by few. He was the descendant of a line who had fought at Crecy , Caen , and Agincourt , and in most of the great battles of his country. He was himself at Waterloo , and his representatives, including the present possessor of the estates, fought through the whole of the Crimean struggle. Mr. Legh was twice married; first to Ellen, daughter of William Turner, Esq., of Shrigley Hall, M.P. for Blackburn, of whom he leaves a daughter, the present Mrs. Lowther; and secondly to Maud, fourth daughter of G. Lowther, Esq., of Hampton Hall, Somerset , who survives him. He is succeeded in his extensive estates by his nephew, Captain William John Legh, now of Lyme.

The remains of Mr. Legh were interred in Disley Churchyard, the funeral being, by his express wish, strictly private. – Warrington Guardian May 23rd, 18J7. The father of the compiler of this book, who sailed for some years as prate on Mr. Leghs yacht, had ever a good word to say of his masters geniality and kindliness of heart ; and when through had health the old gentleman was forced to give up his yacht, he did not forget those who had served him.

Mr William Mercer

was the principal estate agent of the Legh family, for the estates both in Lancashire and Cheshire, and was previously mine surveyor to the above Thomas Legh, Esq. In both capacities he gained the goodwill and respect of the tenantry and all with whom he was brought into contact. He was elected as one of the ten Commissioners on the Newton-in-Makerfield Local Board formed in 1855, and took a prominent part in movements for the good of the district. On September 1st, 1864, he was accidentally thrown from his phaeton whilst turning the corner near Pierpoints farm, Golborne, in the dark, and was picked up in an unconscious state, from which he never rallied, dying the next day of concussion of the brain. He was 56 years of age and unmarried, and was buried at St. Oswalds Roman Catholic Church, Ashton-in-Makerfield.

This text is transcribed by Steven Dowd from the 1916, Vol II, History of Newton in Makerfield by J H Lane, some of the notes in the text are from Mr Peter M Campbell, a person who Lane quoted often in the books he published.

Since I do not know Latin, if there are vocabulary errors or spelling mistakes in the transcription i can only apologise, because you can more than likely directly blame me for the them.

This transcription, its errors and omissions are my own transcription from the original published text and are copyright of steven Dowd,