A FOREWORD

It is with much pleasure that I commend this brief sketch of Winwick Church.

To those who, like myself, have had the privilege of loving and living in Winwick, this beautiful Church stands on a little hill apart, not actually only, but ideally, for it possesses the atmosphere that comes from a long succession of devoted men and women whose worship and service have here been concentrated—the atmosphere that only comes where holy things have been loved and tended for many a day.

In Mr. Pearce’s sympathetic outline the visitor will find that he has in small compass just the outstanding facts that are needful to a clear perception of the special features and beauties of the building—and we hope that these same beauties, and still more the atmosphere of peace that dwells here, may speed him on his way refreshed.

H. G. WARRINGTON. Winwick Rectory, August, 1935.

THE CHURCH OF SAINT OSWALD

PRELUDE

Throughout the whole length and breadth of England we find, as a general rule, that in each old township and village the ancient church of the locality is treasured and well-beloved.

Here, too, within the encircling walls of the church, our ancestors, year by year, century after century, in sincerity and reverence have worshipped God.

To His House, as to a Treasury, our fathers have of devotion, for the adornment of His Holy brought their gifts Sanctuary.

In this spiritual treasury we still find enshrined the romance of Art, the poetic tracery of Symbolism and the rich association of History preserved for our study and for our delight.

In the olden time, folk dreamed of their ideal church as “a Window into Heaven” so it had to be wondrous in its construction and beautiful in its enrichments. “Fair shall be Thine earthly temple! Here the careless passer-by, Shall bethink him, in its beauty, Of a Holier House on high.”

LEGENDS CONCERNING WINWICK.

The fascinating story of Winwick’s noble shrine seems to have its commencement in what some poetic folk call the Mists of Antiquity—by which phrase they mean the “Province of Pre-history.”

Dare we place any confidence at all in the ancient legends of the Country-side ?—May we look for any germ of historical truth in the traditional ” folk-tales,” retold, century after century, by the village children in the precincts of St. Oswald’s beautiful and ancient church?

Little Alice Bytheway,’ as she sat with me in Winwick’s Porch, told the story of the Fairy Pig ; Peg with her golden bell. Almost everyone who comes to our church will ask for the story of the little pig that sits up all alone ” on the west wall of the tower. There he is, looking towards the sun setting —the little pig with the bell chained round its neck, the mascot of Winwick.

Alice says, that in the olden days, our parishioners began to build our church on lower ground—further down the hill.

Day by day, the stone walls were built by our masons on the chosen field—but night by night, (says ‘Alice ‘) the carved stones, laid by day, were mysteriously carried up the hill by a miraculous pig, and re-laid, fair and true, on the higher site.

There are, of course, several churches in Lancashire, where, according to local legend, the masons were helped, or hindered, by the goblins and fairies. Rochdale Church and the church at Samlebury (near Preston) possess similar legends of Goblin-builders.

THE CHURCH OF SAINT OSWALD

Fanciful stories?

Now how do the wise interpret these fanciful stories ? Is the emblematic Pig of Winwick a significant symbol, a hidden clue to the name of some early builder of St. Oswald’s Church or an object of regard ?

Verily ! even as the winged Lion of Venice is a symbol of St. Mark, so, perhaps, the carved pig of Winwick may speak to us, as in a parable, and in the language of Folk-lore, of the fanciful beliefs of the mason who raised the first church here.

What, then, does the Pig represent in the Realm of Archaeology? — Who is this phantom carrier of stones ? this Goblin Mason of Winwick. Some will tell us that he whom we call Puck—in the South of England—is known, in popular tales, as Peg, here in the North. Pich, Pick and Fix are his nick-names. A well-known Goblin-builder—a relic of Antiquity.

This good fairy, Peg, in spite of his many wayward pranks, was sometimes the helper of men ; — Folk said this pixy thrashed the widow’s corn and helped the poor in the Harvest time, unseen—but not ignored by our wonder-loving forefathers ; — ” Peg the Builder.”

Peg 0 Nel is still remembered as the Good Fairy of the River Ribble, as Peg Powler is the Nymph of the River Tees.

These fanciful stories of the fairy folk occupied the thoughts of our British ancestors and have persisted right down the ages, colouring our thoughts even unto the present day.

Early Christianity drove out the pixies with Christian bells 1 How did the Celtic monks countenance the relics of Pre-Christian England ? We believe the Celtic missionaries, on their arrival in Pagan Britain, found the old cult of the elfin gods and goddesses deeply implanted in the people’s imagination.

St. Chad, St. Augustine, St. Dunstan and their contemporaries—just set to work to recapture the popular fancy and proceeded (say the records) to make good Christians out of the fairy spirits.

Even as they used Christian bells to exorcise demons, so perhaps, they chained the bell around the neck of “Peg the Good Helper,” giving him a new name, and incorporating him in effigy into the very walls of Holy Church for a new period of useful service here. We have a popular saying – Belling the Cat.-

After a drawing by Albert Durer, 1450 A.D

Peg and Meg, Kitt and Kate, names familiar in Ancient Britain, stand for both Margaret and Catherine, two Christian saint-names to-day.

Even as Good Megg has become Margaret, so St. Kitt has become Catherine.

Saint Kate, she who is known in Mythology as Good Keg (surnamed the -All Pure,-) has for her symbol —the Pig— which stands also as a symbol for “Pure Saint Anthony”

Another local tale tells how Tony (St. Anthony) trampled on the wallowing pig (the symbol of the lower passions of mankind), even as the Early Christian missionaries stamped out the cult of the lower, baser gods of our pagan ancestors.

There is (what appears to be) a mermaid carved upon a stone on the west wall of the South aisle. We suggest the builders of our church retained some fond memory of Mer Easy ? —a Pre-Christian Nymph of Mersey ? and treasured the lingering legends of the pixy goddesses of Roman and British Verantinium (Warrington) even after the Conversion of Pagan Britain.

KING OSWALD. Leaving the dim realm of Local Legends for the clearer realm of Historical Records we come to the story of Saint Oswald, Winwick’s Patron Saint.

King Oswald, son of King Ethelfrid, restored the lost independence of the Kingdom of Northumbria, and re-established Christianity in this part of the realm, in the seventh century of our era.

The hillock known as Red Bank, north of our Church, is claimed by some authorities to be the site of the king’s palace, here on the frontier of the Ancient Kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia.

Oswald was one of the noblest of our Saxon rulers, a wise and good man, and it is only to be expected that he would have possessed a private chapel within the neighbourhood of his fortified dwelling-place.

The Venerable Bede, eulogizing our Christian king, exclaimed : – Oswald, a man beloved of God.-

As late as the year 731 A.D., (says Bede), Saint Oswald’s miraculous well at Winwick was known to restore health to the Sick ; the waters were said to be of benefit to both man and beast. Ill Fortune is supposed to attend anyone who destroys the surroundings of this ancient fountain of healing.

“Where Winwick’s Brow —

Uplifts the stately spire and draws the feet

To Sainted Oswald’s Pilgrim-haunted Well.”

“This place of yore, did Oswald greatly love,

Who the Northumber’s ruled — now reigns above.”

We recount how the king, with a small body of troops, opposed a great host of pagan Mercians and fell in the ensuing slaughter.

Where, a few centuries before King Oswald’s day, the Roman legions tramped along the old road that intersects the Maserfelth [or Makerfield ?} —there,–says Tradition, on the fifth day of August in the year 642, our patron saint suffered at the hands of Penda, King of Mercia, his enemy.

Some folk say, (perhaps without sufficient authority), that St. Oswald’s mutilated body rested here on the way between the fatal battlefield and the Saint’s Place of temporary Burial. His relics found many Resting Places.

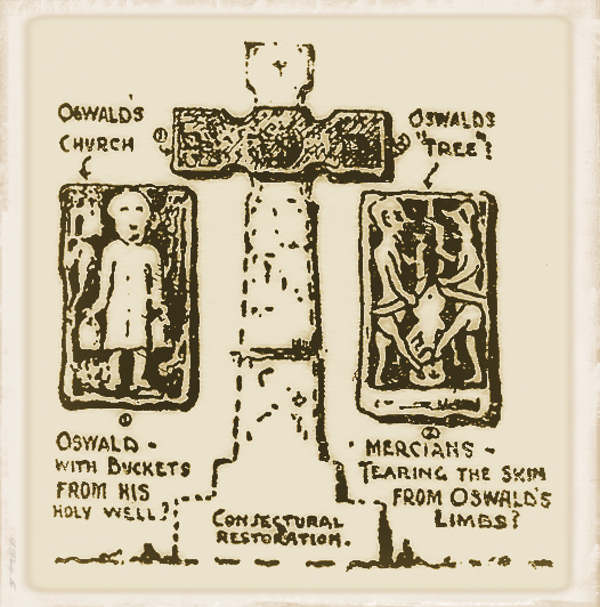

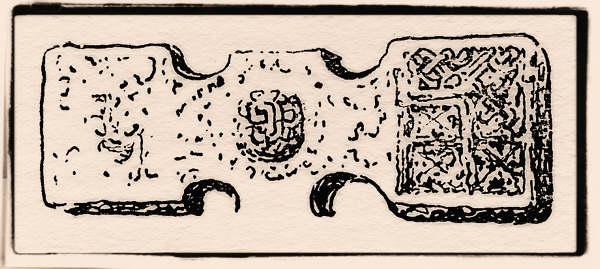

Our church possesses a fragment of a tall Cross of stone ; this relic of Pre-Norman days was re-discovered in 1873 beneath the surface of our churchyard.

It has been computed that the cross stood 12 to 18 feet in height and 5 feet in breadth across the outstretched arms,–one of the tallest and broadest ‘` Celtic type of wheelhead Crosses in Lancashire.The fragment, now preserved in our churchyard beneath the East window, is wondrously wrought with intricate and interlacing Key patterns with Spirals and Knobs. On one end of the Cross arm there is carved a representation of a man carrying what appears to be a pair of bells of Celtic type, (some say the objects are buckets, connected with the stories of the Holy Well). On the other end of the Cross arm there is a realistic. carving showing a portrayal of the martyrdom or, more likely, the dismemberment, of the body of Winwick’s Patron Saint.

We recall the fact that a period of about four hundred and twenty four years lies between the death of St. Oswald and the Norman Invasion of England. How little do we know of this dark period of our history. We can place but little reliance -upon these early records of St. Oswald’s Church, yet they throw a gleam upon our present story.

HISTORICAL RECORDS AND CONJECTURES.

Very little documentary evidence is still in existence relating to the church that stood here in Pre-Norman times.

The Domesday Book of King William the Conqueror, compiled in 1086, informs us that St. Oswald’s Church possessed a vested interest in land of an area sufficient for two teams of eight oxen to plough in a single day.

We gather that before the coming of the Normans our church and her interests and income were in the possession of King Edward the Confessor.

The Norman Conqueror’s famous Captain, Roger de Poitou, (son of Roger de Montgomery, Earl of Arundel and of Shrewsbury, and grandson of Roger the Great—of Montgomery), was at one time leal warrior under the Conqueror and at another time a turbulent rebel. In one of his periods of high prosperity he appears to have acquired the right of ownership in our church and (we assume from records) granted this right to the Priory of St. Oswald’s, Nostell, in Yorkshire, as an Act of Grace.

The grant appears to have been confirmed by Stephen, Count of Mortain,—sometime between the years 1114-1121.—(Stephen became England’s King in 1135).

What was the size and character of our church in the twelfth century ?

Let us further investigate the fragmentary evidences of local legends :-

The floor-line of our nave is some eight or ten feet above the mean level of the adjacent roads, and this fact has helped to lead some fanciful folk to place credit in the tale that a former church once existed (and may still exist) below the floor-line of our present structure.—A lost church of ancient times?

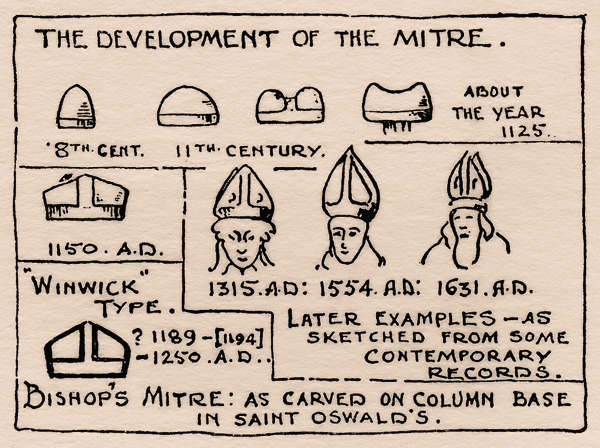

The appearance of truth is given to this theory when we see the portrait-heads of bishops—crowned with mitres—sculptured in stone at the base of some of the pillars of the North aisle arcade.

The carved mitres are in the form of the type of head-covering used by bishops at the end of the twelfth century — — Are these stones the capitals of a range of buried columns ? — is a question that one is sometimes asked.

While we admit that the presence of these portraits, in this position, is a puzzle to many archaeologists, we hasten to say that in our opinion this theory of the existence of a buried structure is altogether too fanciful for our digestion.

Nevertheless, it has been conjectured that these carved bases may be relics of a twelfth or thirteenth century church.

The only portions of this North arcade that appears to have the stamp and character of Norman work are these stone carvings of mitred bishops. It may be suggested that these base stones may at one time have served as corbel stones in some other position and then have been turned about and put to their present use as bases at a later period in a rebuilding.

In the churchyard, in 1840, we found a small Terra-Cotta cup, fashioned in the semblance of a Norman knight ;—possibly a relic of the twelfth-century church that stood upon this historic site.

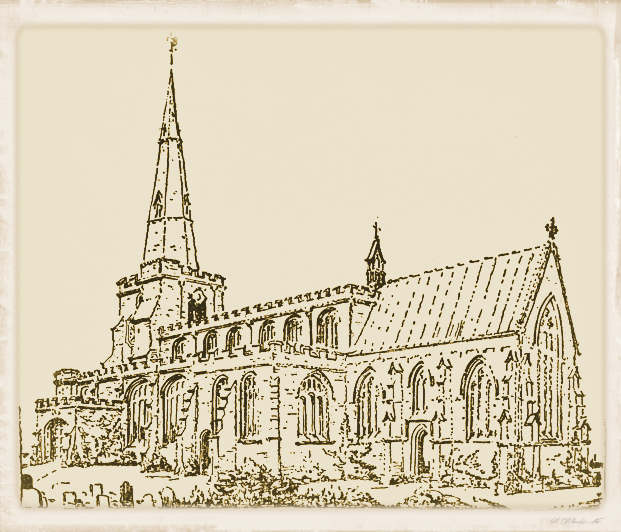

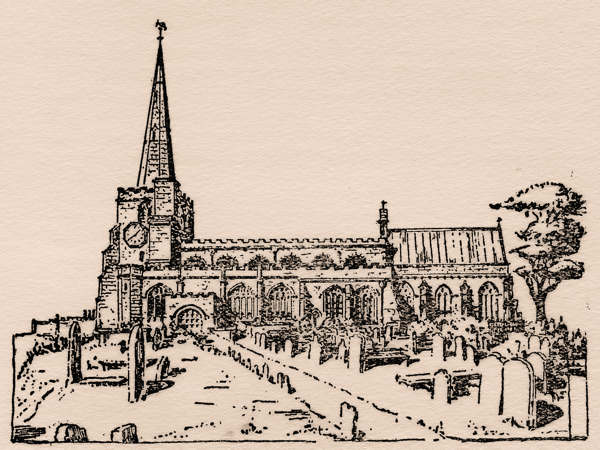

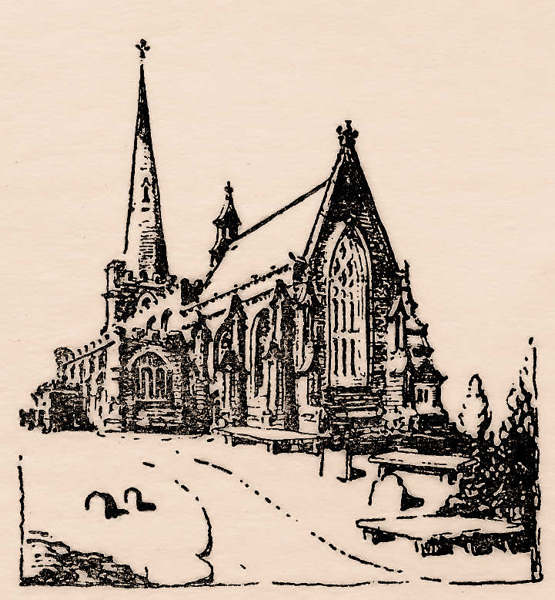

St Oswald’s, South Elevation

Let us review our interesting documents :-

In 1123, the King, Henry the First, wrote to the Bishop of Chester directing that full justice be done to the Prior of Nostell and the Canons thereof.- The Clerks of Makerfield—(the Clergy of St. Oswald’s, Winwick)—were accused of depriving the Prior of dues payable to the Priory.

In 1252 Alexander, the Bishop of Lichfield, having been appealed to by the Prior and Canons, decreed that as soon as a vacancy occurred, a priest of honest conversation and competent learning should be presented by the Priory, that he should, as Vicar, receive the whole of the – fruits of the church and that he should pay to Lichfield Cathedral and to Nostell Priory a sum of money of an amount to be hereafter fixed by Lichfield’s Bishop.

The church—at about that time—paid a pension of 50s. to Nostell, but, in the future (say the records) the Cathedral was to have one half, as an immediate contribution– cash down,” as the saying has it.

In 1264 the Bishop appealed for the King’s aid against certain persons who had seized the church funds.-

In 1291, the year after the Expulsion of the Jews from England,—Winwick’s Church was assessed at £26 13s. 4d., in the day when a goose could be bought for eightpence and a cottage for twenty pounds.

Some authorities say that a part of the Nave, the North aisle and (possibly) the lower portion of the tower of our present church were rebuilt—or underwent some considerable restoration —in the reign of King Edward the First.

John de Langton, in 1307, claimed the patronage of the church in right of his wife, Alice, heiress of the Lords of Makerfield, but the Prior and Canons of Nostell put forth a clear title and a better claim.

In 1341, the tax of “Ninths” of corn, wool, &c., was valued at 50 marks or thereabouts.

Somewhere about 1350 a pension of 24 marks was due to the Monastery—presumably a Vicar’s pension—and at about this time, the Duke of Lancaster laid claim to be the patron of our church and demanded Patrons Rights and Payments.

Some competent archaeologists maintain—with some reserve—that the spire and a portion of the Southern arcade of the Nave (before its more modern rebuilding in 1836) were erected in the year 1358.

Stone carvings, representing shields of Sir Gilbert de Haydock and Sir Gilbert de Southworth, contemporary knights of this period, are upon the upper part of the steeple.

The moulded pillars of the North Arcade of the Nave, though supposed to have been rebuilt a few years before 1600, have some of the characteristic architectural features of work of the fourteenth century.

We will suggest—later on—that the present columns (with their alien caps and bases) appear to have been built from many miscellaneous fragments—possibly relics of earlier buildings that stood within our precincts.

ROMANTIC SIDELIGHTS ON WINWICK’S STORY.

From about the year 1381, (time of King Richard the Second) until the reign of King Henry the Sixth (1433) the patronage of St. Oswald’s Church lay in the possession of the English Crown. The possession was disputed by many rival claimants.

When King Henry the Sixth confirmed the Grant of our Church of St. Oswald to Sir John Stanley, a reservation was made of an annual pension of 100 shillings to the Priory of Nostell.

A note in our church records reminds us that the Priory sold the remainder of the patronage to Sir John Stanley in 1433 (or 1434).

We have but a few architectural features of the fifteenth century left here undisturbed, with the exception of a fragment of an ancient Rood Screen (a beam now preserved in the Vestry). This relic of the period has eleven brackets for images and is about 15 feet in length and is considered to have been the front beam of our chancel screen. The date of the work is computed to be about the year 1481.

The fragment, with its interlacing vine branches carved upon it, resembles the main beam of the Rood Screen at Mobberley Church, Cheshire—and is rather similar to that of the Rood Screen at Campsall, Cheshire. It is probably the work of a carpenter who was a contemporary of Columbus.

In our List of Rectors, you will find many records of those who bore the honoured name of Stanley.

One July night in 1495, King Henry the Seventh slept at Winwick during the time James Stanley (he who became Bishop of Ely) was our rector.

James was the son of Thomas, Lord Stanley—who (in 1485) had been created Earl of Derby by King Henry the Seventh on Bosworth Battlefield.

Our rector is described as -“a talle goodlie man as was in alle Englande.” He spedd well alle matters that hee tooke in hande.-

It is reported that he stood six feet eight inches in height —and (the rhymer says) he was a greate Vyander—as any in hys dayes.- The Rhymer Was a kinsman, named Thomas Stanley (Bishop of Man), Rector of Winwick sometime between 1532-1568.

From several historical sources we learn that Rector James Stanley organised a Cockefyghte at Winwick, a cruel battle that took place on the 27th April in the year 1514.

On the 3rd day of May 1495 the King’s Constable of England sat in judgment over a Tuzzle of Arms and Heraldry between Sir Thomas Asheton and our Sir Piers Legh. Our rector, James Stanley, was present and acted aa a Witness.

In 1513, James’s son, John, led in his father’s stead, a great body of troops at the Battle of Flodden.

“Every burne had on his breast broudered with goulde

a fote of the fairest foule that ever flowe on winge”

—the embroidered badge of the Stanley—seen upon many a grim battlefield.

Rector James Stanley, Bishop of Ely, and in 1493 rector of our church, died on 22nd March 1515.

WINWICK’S CHANTRY CHAPELS AND EFFIGIES.

“Sephulchal stones appeared with Emblems graven, And foot-worn Epitaphs, and some with small and shining Effigies Of brass inlaid.”

THE LOST CHANTRIES.

In the olden time, there were Chantry Altars and Chapels beneath our roof wherein prayers were offered for the souls of donors and their nominees.

One chantry, in our Chapel of the Holy Trinity,” was, in 1330, made by Gilbert de Haydock. “A fit and honest Chaplain was appointed to pray for the founder by name, every time a mass was sung.

A later foundation—Stanley’s Chantry—in St. Oswald’s, lay in what we named the Rector’s Chapel.- It was duly endowed with the rents of certain houses and lands (burgages) in Lichfield and Chester and was worth about 66s. 8d. per annum.

All chantries in England were confiscated in 1548 under a law of King Edward the Sixth.

There is some indication that about six years before this confiscation, but in the time of King Henry the Eighth, Sir Peter Legh of Lyme, presented a chantry priest to St. Oswald’s Church here at “Wynwych.”

THE SOUTH CHAPEL.

The Chapel of the Leghs of Lyme (formerly the Chapel of the Holy Trinity—in Winwick Chapel) possesses a moulded roof inset with plaster panels and timber wallplates where, at intervals, beneath the ends of the beams, there are carvings representing angels holding heraldic shields.

The Chapel contains amongst its treasures a metal monument showing the fine effigy of Sir Peter Legh and of his lady. The date is 11th August 1527.After the death of Lady Ellen (Savage) in 1491, Sir Peter sought the comfort of Holy Church and was ordained a priest. On this historically – precious memorial he is shown tonsured and with mass vestments over his armour. Lady Ellen is engraved as in her shroud. Below the figures of Sir Peter and Ellen there were engraved the figures of their children.

Sir Peter Legh of Lyme, died at Lyme in 1527, and was buried in our church.

He was King’s Steward of Blackburnshire, Tottington, Rochdale and Clitheroe.

A dated Will, still in existence, directed that he desired to have an impressive funeral, that his horse, his Standard and his armour be carried to our church, and that masses should be sung for his soul’s peace Every priest to have for his trouble —fourpence and that a fitting dinner – be provided for his mutes and mourners

AREVERIE.

We can imagine the magnificent scene of stately pageantry, the richly-elaborated procession proceeding by the light of innumerable torches, entering the gateway of our church to the solemn dirge of the choirmen and hired singers—the ceremony interrupted by the neighing of Sir Peter’s war-horse bemoaning his dead master ; the gloom, the glory, the lordly pomp of it all! We can see, in fancy, our church aglow with the light of many candles as the body of the knight is borne to its rest.

Imagination under the guidance of historical research, helps us to understand the story of our glorious and ancient church and her picturesque associations of romance and poetic beauty.

Within the Legh Chapel there are later monuments ; one, to another Peter Legh, 1635 ; another to Richard and Elizabeth his wife, 1687 ; and still another, in classic guise, to Ellen, wife of Thomas Legh, 1831.

There are, likewise, the remains of a destroyed monument built into the walls and consisting of panels of alabaster with heraldic decorations and strap-work of the Jacobean Period of architectural design.

The present organ occupies the place where in the olden time the pilgrims knelt.

THE GERARD CHAPEL.

On the North side of the church stands the Chapel of the Family of Gerard, Lords of Bryn.

Beneath an elaborate carpet we have a fine metal monument of great size. Engraven upon the monument there is a full-length figure in armour ; surrounding the figure there is an elaborate framework of “canopy-work” and an interlacing ribbon bordering.

The figure represents Peter Gerard of Kingsley and Bryn, a member of a noted Roman-Catholic family. The figure of the knight is engraven in a surcoat (or tabard) bearing an engraved lion, rampant, crowned. Gerard’s hair is shown long and waving, his hands clasped as in the act of prayer.

Peter Gerard married Margaret, daughter of Sir William Stanley of Hooton, Cheshire.

The local seat of the Gerards, the moated hall of Bryn, was at various times a refuge for hunted priests in the Days of Persecution and in times of religious intolerance.

YEA, there is an “atmosphere of Peace” within the silent chapels of Winwick Church and we are worthily proud in the possession of these wonderful and interesting Memorials of the Past, these ancient records in engraved metal, in carved marble and – stones with emblems graven,- eloquent of olden days and golden yesterdays.

WINWICK CHURCH IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY.

We have found pleasure in tracing the lines of structural alterations that have taken place in our church in the course of ages.

The Old Chantry chapels have been altered as fresh needs demanded change.

There runs an inscription —(or a part of one)— carved on the Western end of our South aisle, externally :-

O blest one, [Oswald] hear!

When here on thee we call,

In fifteen hundred and just three times ten

Sclater restored and built this wall again;

And Henry Johnson, here was Curate then.

–

At about this date —or soon afterward— Leland, King Henry the Seventh’s Librarian, passed through the Rector’s park and probably was the rector’s guest.

In the year 1534, the net value of our church was reputed to be £102 9s. 8d. —when eggs were six for a penny.

The Registers of Christenings, Marriages and Burials commences with the year 1563. Of earlier records : — — – the first (paper) book is not known to be in existence to-day, but it has been suggested that the earliest entry therein was made in 1550 ?”

One of our bells is thought to date from somewhere about the year 1600, it bears the initials which have been taken to stand for Peter Legh, Thomas Gerard, Edward Eccleston, Edward Stanley, Thomas Stanley and John Rider.

The tower to-day contains a peal of six bells ; (some, at least, of the six are old and were recast in 1711).

Before we leave the records of the sixteenth century let us recall to mind the names of a few of our rectors of that age and date :-

(1) In 1524, William Bulloyne—” said to be a kinsman of the new queen “—(Anne Boleyn. mother of Queen Elizabeth).

(2) Rector John Caldwell was called upon to pay for, (or to provide,) two horses for the Elizabethan Muster of 1585/6 when Elizabeth sent military aid to the Netherlands.

(3) John Rider, our rector at the end of the sixteenth century and who became Bishop of Killaloe in 1612, was a literary man of some note.

Further details are given in the Lancashire Section of the – Victoria County History.”

THE NAVE ARCADES.

As already hinted, the story of the North arcade of the Nave contains an interesting but evasive problem —the subject of much speculation and debate.

Firstly :— the column bases — with their carved portraits of mitred bishops, appear to have but little relationship with the columns that they support.

Secondly :— Let us notice the columns—the great clustered shafts, moulded in the style of the fourteenth century yet supposed to have been erected in the seventeenth—or re-erected then.

Thirdly :— Let us compare the great width across the capitals of these column shafts with the much reduced thickness of the arched wall above these wide, projecting caps. Here is a mystery. Here, perhaps, is the explanation :-

(1) The bases are evidently of much older and earlier date than the columns they now carry.

(2) The columns of moulded shafts are apparently made up of ancient fragments, re-dressed and re-set at a later re-building.

(3) The wide capitals of these shafts appear to have been designed originally to bear upon their wide inner projection (that is—on the edge nearest the centre line of the church) still

higher shafts that would have been continued right up the inner face of the wall of the clerestory, in order to carry the corbelled supports of the roof.

Possibly the original clerestory, with shafts running up the face of the wall, was destroyed at the time of the Civil War when the church was under gun-fire ; these wall shafts – have not been reproduced in the re-erection of the upper part of the walls in the present clerestory.

There is a persistent theory that the arched and windowed wall above the columns of this North arcade of the Nave was rebuilt, at its present greatly-reduced width, in, or a little earlier than, the year 1701.

We have historical evidence that the present fine -Jacobean – woodwork of the roof of the Nave is supposed to belong to that year—though one uses the word “Jacobean,” in this case, with some reticence—remembering that the Jacobean style truly belongs to a slightly earlier date.

In 1692 the Hon. Henry Finch, of the family of the (then) Earl of Nottingham, was rector of Winwick.

He became Dean of York, and to him we owe the gift of this timbered roof now existing.

Possibly the North Clerestory wall of the church was rebuilt, at the end of the seventeenth century, to carry this present roofing and with the original – wall-shafts – omitted.

The South arcade of the Nave, is of an altogether different design, both in mouldings and in character, to the North arcade.

We hesitate to name the date of the original work, as it is generally accepted that the stones of the whole of the South arcade were re-dressed and re-built (with material then existing) in the year 1836, and many clues to its history may have been lost in the course of rebuilding.

The aisle roof, originally belonging to the year 1530 [1699 has been replaced in modern times.

Old corbels, set high in the wall, to carry roof timbers, indicate the position of former beams.

So, from these clues we are able with some degree of accuracy, to reconstruct, in imagination, the lost architectural records of our ancient church.

St. Oswald’s—a few years ago.

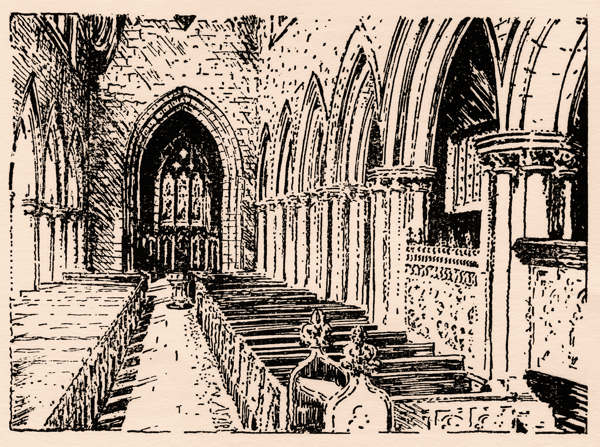

Interior, looking towards the Western arch from the South end of the Chancel screen.

In the reign of King James the First, Tobias (or Josias) Home was rector, but he was succeeded (in the second year of the reign of Charles the First, the Martyr-king,) by Charles Herle, a Puritan of some eminence.

Herle, in time, joined the Presbyterians and won a measure of renown under Cromwell.

During Herle’s rectorship, in 1641, our church reported the presence (in Winwick) of 244 recusants, non-attenders at our church.

In the August of the following year King Charles set up his banner at Nottingham, and England fell into all the horrors of the Great Rebellion.

How fared St. Oswald’s in the Civil War?

Near Red Bank, N.W. of our church, Colonel Assheton’s Roundheads, on their forced march to the Siege of Warrington, attacked the Cavalier troops who had barricaded Winwick Church and were attempting to hold it against the rebels.” This took place in the month of May 1643.

The Tide of War ebbed and flowed around our church walls.

Following the Battle of Preston the Parliamentarian troops under Lieut. General Cromwell—pursuing the broken forces of the Duke of Hamilton under General Bailey, on the 19th August 1648 met in battle at Red Bank near Winwick. The Royalists — “to the number of one thousand,” (says one report,) took refuge (or were imprisoned) in St. Oswald’s, and—being overcome by the Cromwellians, were disarmed and some were executed to Warrington.

Within a year, King Charles, himself, was executed in Whitehall and Cromwell took supreme power.

In 1651, King Charles the Second, in the days of his exile, was at Winwick.

Thomas Jessop became our rector in 1659 but, at the Restoration, Dr. Richard Sherlock—” the royalist who never shaved his beard after the murder of King Charles the First,” was presented, by the eighth Earl of Derby, to the rectory of Winwick.

Sherlock, ” a pious and worthy man, much given to prayer and fasting,” spent the greater part of his income on charity.

He made a gift of £50 to the poor of Oxton, (his birthplace,) and a ” Bread Dole to Woodchurch, where his father was, at one time, rector.

On our Chancel step you will see Sherlock’s Memorial Brass. At his wish, the plate bears the words :— “The remains of Richard Sherlock, the very unworthy Rector of this Parish.” We know his true worth, his modesty, his integrity and his great heart of charity and kindliness.

He died in 1689 and was succeeded by Dr. Thomas Bennet who, in turn, was followed in 1692 by the Hon. Henry Finch, Dean of York, donor of at least a part of the present roof of our Nave, here, at Winwick.

The fragment of St. Oswald’s Cross.

Dr. Kuerden, passing through our village in the last days of the seventeenth century, described St. Oswald’s as “a faire built churche — — a remarkable fabric” — Today we endorse his verdict. The history that is known and here recorded is but a little of all the wondrous story, the glory, the glamour of this

ancient place.

The Society of Friends, of Warrington, presented our church with the fine chandelier in brass—a tribute of fellowship.

The French Flag, that hangs in the church, was taken at the Battle of Lissa in 1811, and has associations with Admiral Phipps, son of Rector Geoffrey Hornby.

The flag is a link with Nelson’s day and the Napoleonic Wars.

THE UNFOLDING YEARS.

The South Porch was built (or re-built) in 1721 and the Altar Table—now in the Vestry—dates from 1725— the year when Rector Francis Annesley was installed.

The Hon. John Stanley, D.D., brother of the eleventh Earl of Derby, is com memorated by a brass plate and marble Memorial tablet within the church.

Seven times in St. Oswald’s history has a Stanley held the rectorship ; several other rectors, including the Hornbys (father and son) and their successors Hopwood (1856) and Penrhyn (1890) have been related, through marriage, with this honoured and ancient family.

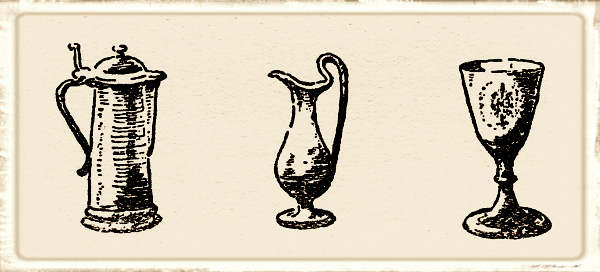

The Church Communion Plate includes the following :2 chalices, patens and flagons (1786).

There are also 2 chalices, 4 patens and 2 flagons, dated 1795, and a sifter and tray of the same period.

The fragment of St. Oswald’s Cross.

Pugin, the architect of the restored chancel, designed 2 plates for our church, and we have among our treasures an ebony staff with plated head, the gift made to the church by Geoffrey Hornby, who became rector of St. Oswald’s in the closing years of the eighteenth century,” (1781).

The Reverend James John Hornby performed the ceremony (in London) when, in 1797, the celebrated actress, Elizabeth Farren, – that fine, strong and noble character,” was married to the Earl of Derby. James John Hornby was rector of Winwick, 1812-1856.

The limited space at our disposal in these notes makes it impossible for us to give more lengthy biographical records of the whole of our rectors and curates.

THE NINETEENTH CENTURY.

During excavations beneath the floor of the church in 1828, some gigantic skeletons, laid one upon another and covered by a rude heap of sandstone blocks of cubical shape, were discovered by our workmen. The discovery led to much speculation as to the history of these human documents.”

There is a persistent theory that St. Oswald’s Church stands upon the site of an Altar of the Druids.

St. Oswald’s Chancel, ” injured in the Great Rebellion,” was rebuilt in the year 1847-8 during the time that James John Hornby was rector.

It has been described as a fine imitation of the style of Gothic architecture of the fourteenth century.”

A. W. N. Pugin was the architect and George Myers the builder.

The East window has pictorial representations of the Apostles and Evangelists, the other (three) windows in the Chancel suggest Our Lord, as Prophet, Priest and King.”

During excavations in 1877, we discovered an ancient font, buried beneath our church. The font now lies in the churchyard, below the East window.

The workmanship of the font belongs to the early part of the fourteenth century,—a date when a considerable amount of building work took place here.

The present font is of relatively modern date—though it is carved in the style and shape of a font of the fifteenth century.

A scholarly account of Winwick Church and her Clergy through the centuries may be found in William Beamont’s Winwick : its History and Antiquities.

The three most recent rectors of St. Oswald’s,—Martin Linton Smith, D.D Edwin Hone Kempston, D.D., Herbert Gresford Jones, D.D., have been created Bishops Suffragan of Warrington.

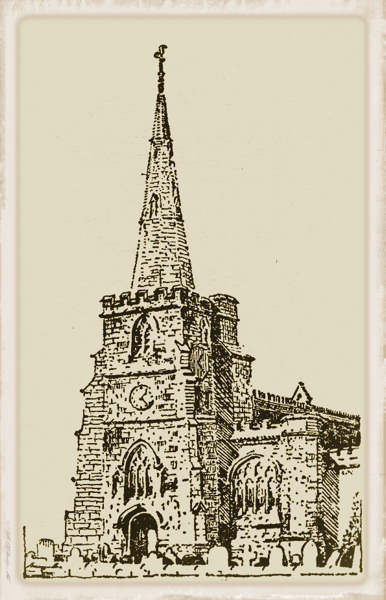

The East end of the Church.

“Ascend the tapering spire That seems to lift the soul up, silently, To Heaven — — with all its dreams.” With these words in our mind we will briefly review the long records of our beautiful and ancient church, her treasures and mysteries.

We have endeavoured to trace the original meaning of the Winwick Pig ;- to dispose of the legend of the buried church -; to solve the problem of the medley architecture of the North arcade of our Nave and to put into some form of historical sequence the main points of architectural development of our gracious sanctuary.

Here our tale draws towards its conclusion.

In its telling, we have had a distant view of King Oswald the saint, the Liberator, the Missionary.

We have, in imagination, seen Roger, the Norman, conveying the church to the Prior of Nostell—in the long ago.

Then, into our story came the magnificent, powerful and pleasure-loving Stanley, Vyander – and bishop, with his lordly retinue all arrayed in embroidered livery in a gilded period of English History.

As the pageantry unfolds we have glimpsed the spectacular funeral procession as it passed by torchlight to the Burial rites of Sir Peter Legh.

The next scene depicted an episode in the Great Rebellion, with King Charles’ Cavaliers trapped in our church tower and then—across the range of vision of our imagination—we have seen Rector Herle, the Puritan, winning his way from Winwick to Westminster and to the favour of Cromwell and his Ironsides.

With the Restoration, came Rector Sherlock the gallant Royalist, pious, unassuming,—composing his own derogatory epitaph and then, in the course of the passing years, we discovered some of the clearer records and interesting episodes of our own century.

Just while these notes are being written the twilight is falling and we sit, in thoughtful reverie, upon the stone bench by the churchyard gate.

Here, in the gathering gloom of an Autumn evening we dream of the glories of St. Oswald’s Church as the rich memories and illuminating records of this ancient fane unfold themselves to our delight.

May we ever honour and preserve this priceless House of God and let us treasure—for all time—all that is therein fair and beautiful, all that we may find glorious, inspiring and of Good Report.

So shall we honour God within His Holy and beautiful Sanctuary, and bequeath this historic and gracious heritage to the generations that are yet to be.

St Oswald’s Church, Winwick

This article is transcribed from original source owned by Steven Dowd, this transcribed version, it’s text and photos are ©2007 Steven Dowd.