Its Political Importance

During the 274 years from 1558 to 1832, Newton was represented by no fewer than 70 different members, and from 1678 (the year the name “Tories” was given to a political party) it was represented exclusively by 30 Tories. In this list of members are found the names of the lords of the manor?the Langtons, the Fleetwoods, and the Leghs?and many gentlemen of rank and importance in the country.

It was represented for six years (1695 to 1701) by Thomas Brotherton, Esq., of Old Hey Farm, situated near the Vulcan Foundry. For twenty-nine years (1714 to 1743) it was represented by William Shippen, Esq., mentioned by Alexander Pope, in his “Imitations of Horace,” as “downright Shippen” in allusion to his outspokenness.

During the reign of George I. (in 1717) Shippen was committed to the Tower for reflecting on the kings speech, the honourable member having said ” that the second paragraph of the speech seemed rather to be calculated for the meridian of Germany than of Great Britain, and that the king was a stranger to our language and constitution.”

The nomination of members of parliament was in the lord till the year 1620, after which time the franchise became vested in the free burgesses, that is, in persons possessing freehold estates in the borough, of the value of 40 shillings. a year and upwards, of which there were about sixty who claimed to vote; but the burgage tenures being chiefly in the lord of the manor, the nomination of the members was as much in him after the right came nominally into the hands of the burgesses as it was before that time, and hence Newton ranked among the nomination boroughs that returned two members, that is, up to the period of its 1832 disfranchisement.

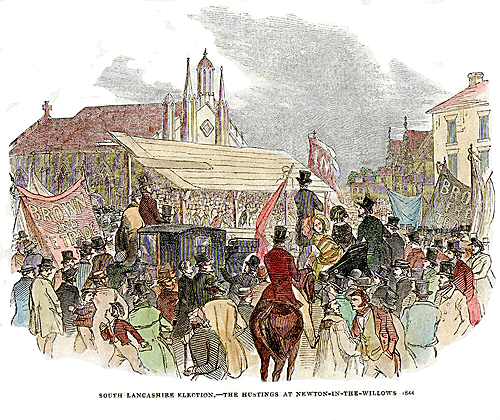

The South Lancashire Elections 1844. This is a view of the Hustings (electorial meeting) held ouside St Peters Church, Newton High St (no tower on church, and Obelisk just showing behind the stand). The banners declare BROWN for FREE TRADE

Newton – a little poor market Leland called it – first sent Members to Parliament in 1559. No authority has been found for its enfranchisement, but its first Members were not challenged in the House.

The 1559 return is to testify that we, the free men of the borough of Thomas Langton, knight, baron of Newton … have elected Sir George Howard and Richard Chetwode Esquire, with the assent of the burgesses, to Parliament.

The return was signed by Sir Ambrose Cave, chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster, and by William Fleetwood I`, the steward of the said borough. Fleetwood had many connexions with the duchy and in addition was related to the Langtons. This last fact probably explains why the duchy picked on Newton when it set out to obtain the enfranchisement of an extra borough.

The names of the first two Members indicate that if Cave and Fleetwood were responsible for the enfranchisement of the borough, the deal was concluded through Sir William Cecil, who was given in return the nomination of the 1559 MPs. One of them was the brother of Queen Catherine Howard, Queen Elizabeths cousin no less. The other described Cecil as his dear father, and Cecils interest in him is apparent from his noting Mr. Chetwoods case as a subject for attention the day after Elizabeths succession.

Francis Alford (1563) also had connexions with Cecil, but here the resemblance between 1559 and 1563 ends, for the second 1563 Member, Ralph Browne, was a protege of Cave, whose will he witnessed (unless, of course, there is confusion here with another man of the same name).

Both 1571 men were connected with the Exchequer, Anthony Mildmay through his father Sir Walter, and Richard Stoneley through the new chancellor of the duchy Sir Ralph Sadler. John Savile I (1572) had a connexion with the duchy and John Gresham (1572) With William Fleetwood I.

The influence of the duchy now came to an end, for by 1584 the grandson and heir of Sir Thomas Langton (d.1569) was of age, and for the rest of the reign he chose the Members, with the single exception of William Cope (1597) who seems to have owed his seat to Cecil.

The Langtons were Catholics, though Robert (1584, 1586) conformed, and Thomas Langton himself did not sit while he owned the borough.

In 1594, however, he sold it to the Fleetwoods with the nomination, election and appointment of two burgesses of the Parliament.

In 16o1, when Langton needed to avoid his creditors, he arranged to be returned to Parliment and the other 1601 MP was the steward of the borough.

By this time Newton had a second borough official in the bailiff, who acted as returning officer.

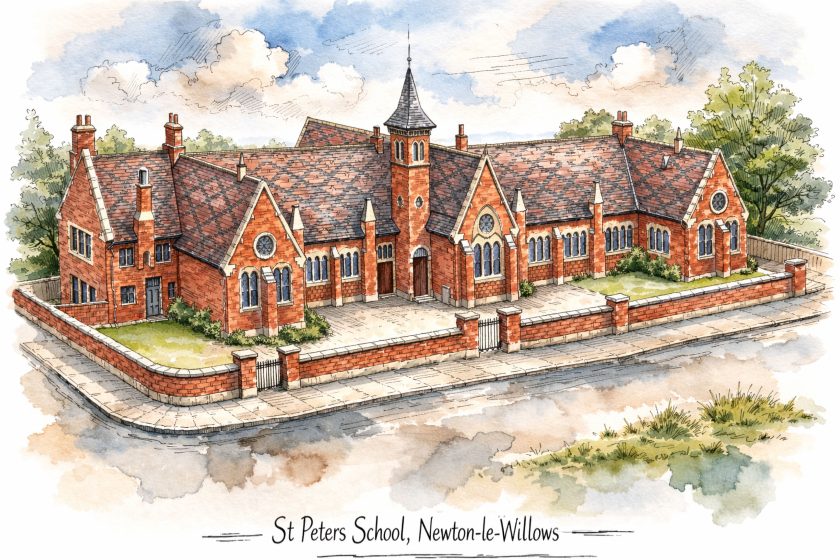

For seven years (1818-1825) it was represented by Thomas Claughton, Esq., of Haydock Lodge, the father of two dignitaries of the Church?Thomas Legh Claughton, Bishop of Rochester, afterwards Bishop of St. Albans, and father of the present chairman of the L. & N. W. Railway; and Piers Calveley Claughton, first Bishop of St. Helena, then Bishop of Colombo, and afterwards Archdeacon of London. The latter was christened and con-firmed in Newton Church, and in 1859 gave an address to the school-children on the occasion of the laying of the foundation-stone of St. Peters Schools. The last two members were Thomas Legh, Esq., and Thomas Houldsworth, Esq.

Untill the year 1832 Newton retained so much of its ancient dignity, that it returned two members to parliament. This was not, however, amongst the number of the ancient Lancashire boroughs; for the earliest exercise of the privilege is only of the date of the first of Elizabeth, at which time the members were nominated by the steward of the lord of the barony,* and with the assent of the lord of Newton. Though no corporate body, Newton has these arms assigned to it, viz.: Out of a ducal coronet, a rams head holding in his mouth a sprig.

After its disfranchisement in 1832, Newton became a polling station for the election of members for the division of South-West Lancashire. In 1865 Mr. Gladstone was returned as one of those members, defeating William John Legh, Esq., who had held the seat since 1859. Many of us remember Mr. Gladstones visit to Newton, his speaking from the hustings alongside the Town Hall, and the presentation of an address to him by Mr. John Ball and Mr. Robert Palmer, on behalf of the Liberal Party, in the Legh Arms Hotel. At the General Election of 1868 Richard Assheton Cross, Esq., defeated Mr. Gladstone by 313 votes, and remained one of its Tory members until 1885, when the Redistribution Act was passed, making Newton a separate division with one member. In that year the late Colonel McCorquodale entered the lists against Mr. Cross, but was defeated by a majority of 383. On Mr. Crosss elevation to the House of Lords, in 1886, Thomas Wodehouse Legh, Esq., contested the division, and was returned with a majority of 70 7 over his opponent, Mr. D. OConnell French. Mr. Legh held the seat until the death of his father in December, 1898, and his own consequent elevation to the House of Lords, when the late Colonel Richard Pilkington was returned unopposed. He continued. its member until the election in January, 1906, at which he was defeated by Mr. James Andrew Seddon.

LIST OF THE MEMBERS FOR NEWTON, FROM 1558 TO 1831.

1558.9. Geo. Haward, knt.? Rich. Chetwood

1563. Francis Alford, Esq.? Ralph Browne, Esq.

1571. Anthony Mildmay, Esq.? Thos. Stoneley, Esq.

1572. John Gresham, Esq.? John Savile, Esq.

1585. Robert. Langton, Esq.? Edw. Savage, Esq.

1586. Robert. Langton, Esq.? Edw. Savage,

1588. Edw. Trafford, Esq.? Robert. Langton, Esq.

1592. Ed. Trafford, Esq.? Robert. Langton,

1597. WILLIAM COPE – GEOFFREY OSBALDESTON

Robt. Langton, Esq.

1601. Thos. Langton, baron of Walton.? Rich. Ashton, gent.

1603. John Luke, knt.? Rich. Ashton, gt.

1614. Miles Fleetwood, knt.? Thos Gerard, knt.

1620. Geo. Wright, kt.? Rich. Kippax, Esq.

(Assensu Ric. Fleetwood Baronetti Domini villa;)

1623. Thos. Chernock, Esq.? Edm. Braes, gent.

1625. Miles Fleetwood, knt.? Hen. Ed-wards, knt.

1625. Miles Fleetwood, knt.? Hen. Edmonds, knt.

1628. Hen. Holcroft, knt.? Francis On-slow, knt.

1640. Rich. Wynne, knt. and bart.? Will. Lambert, Esq.

1640. W.Ashurst,Esq.? Roger Palmer,knt.

Peter Brook, Esq.

1653-4-6. No returns.

1658-9. W.Brereton,Esq.? Peers Legh,Esq.

1660. Rich. George. ? Rich. Leigh

1661. Rich. George. ? Rich. Leigh

1678. Sir J. Chichley.? Andrew Fountain.

1681. Sir J. Chichley. ? Andrew Fountain.

1685. Sir J. Chichley. ? Peter Leigh.

1688. Sir J. Chichley. ? Francis Cholmondeley.

1690. John Bennett ? Geo. Cholmondeley.

1695. Leigh Banks ? Thomas Broughton.

1698. Thomas Leigh ? Thomas Broughton.

1701. Thomas Leigh ? John Leigh.

1702. Thomas Leigh ? John Ward.

1705. Thomas Leigh ? John Ward.

1708. Thomas Leigh ? John Ward.

1710. Thomas Leigh ? John Ward.

1713. Abraham Blackburne ? John Ward.

1714. Sir Francis Leicester ? William Shippen.

1722. Sir Francis Leicester ? William Shippen.

1727. Leigh Master ? William Shippen.

1734. Leigh Master ? William Shippen.

1741. Leigh Master ? William Shippen.

1747. Peter Leigh ? Sir Thomas Grey Egerton.

1754. Peter Leigh ? Randal Wilbraham Bootle.

1761. Peter Leigh ? Randal Wilbraham Bootle.

1762. Peter Leigh ? Randal Wilbraham Bootle.

1768 Peter Leigh ? Anthony J. Keck, Esq.

1774. Robt. V. A.Gwillim,Esq. ? Anthony J. Keck, Esq.

1780. Thos. Peter Leigh, Esq. ? Thomas Davenport, Esq.

1784. William Peter Leigh, Esq. ? Sir Thos. Davenport, knt.

Thomas L. Brooke, Esq.

1790. Thomas L. Brooke, Esq. ? Sir Thos. Davenport, knt.

1796. Thomas L. Brooke, Esq. ? Sir Thos. Davenport, knt.

Thomas L. Brooke, Esq.

Peter Patten, Esq.

1801. Thos. Brooke, Esq. ? P. Patten, Esq.

1802. Thos. Brooke, Esq. ? P. Patten, Esq.

1806. Thos. Brooke, Esq. ? Peter Heron, Esq.

1807. Thos. Brooke, Esq. – Peter Heron, Esq.

1812. J. J. Blackburne ? Peter Heron, Esq.

1819. Thomas Claughton ? Thos. Legh.

1820. Thomas Claughton ? Thos. Legh.

1826. Thos. Alcock ? Thos. Legh.

1830. Thos. Houldsworth ? Thos. Legh.

1831. Thos. Houldsworth ? Thos. Legh.

The British Reform Act of 1832 introduced the first changes to electoral franchise legislation in almost one hundred and fifty years. It met strong opposition from the Tories, who had defeated earlier bills, and it required pressure on William IV and the resignation of Earl Greys Whig government to pass.

The Act extended the franchise into the middle classes. Propertied male adults paying a annual rent of ?10 or more (?2 in the rural counties) could vote. The vote was also extended to those with copyhold tenure of ?10 or more and leaseholders or tenants-at-will paying ?50 in rent. These changes increased the electorate from 435,000 to 652,000 (1 in 7 males) and gave greater political influence to urban centres in the north while leaving the rural areas under aristocratic control. The Act also abolished 56 rotten boroughs and removed one MP from boroughs with less than 4,000 inhabitants. Before the Great Reform Act of 1832 it was a rotten or pocket borough, one which sent two members to Parliament but which had a tiny electorate controlled by the local magnate, who therefore had the election ?in his pocket?. It is said that when somebody referred to a particularly egregious example of a rotten borough, say one in which every voter was a man employed by the landowner

The term rotten borough (or pocket borough, as they were seen as being “in the pocket” of a patron) refers to a parliamentary borough or constituency in the Kingdom of England (pre-1707), the Kingdom of Great Britain (1707-1801) and the Kingdom of Ireland (1536-1801) which due to size and population, was controlled by a patron and used by a patron to exercise undue and unpresentative influence within parliament. Though rotten boroughs existed for centuries the term rotten borough only came into usage in the 18th century.

In such constituencies and boroughs, due to the small number of electors, the post of Member of Parliament could effectively be bought. Because the constituencies were not realigned as population shifts occurred, MPs from one borough might represent only a couple of people (giving those people a relatively large degree of political representation), whereas entire cities (such as Manchester) might have no representation at all. Examples include: Old Sarum in Wiltshire had eleven voters, Dunwich in Suffolk had 32 voters, Plympton Earle with 40 voters, and Newtown on the Isle of Wight with 23 voters (all figures for 1831). All of these boroughs could elect two MPs. At one point, out of 405 elected MPs, 293 were chosen by less than 500 voters. (Spielvogel) Many such rotten boroughs were controlled by peers who gave the seats to their sons, they thus having influence in the House of Commons while also holding seats themselves in the House of Lords. The Duke of Wellington, prior to being awarded a peerage serveed as MP for the rotten borough of Trim in County Meath in the Irish House of Commons.

In addition, there were boroughs where parliamentary representation was in the control of one or more patrons by their power to either nominate or other machinations, such as burgage. Patronage and bribery were rife during this period. In some cases, wealthy individuals could “control” multiple boroughs — the Duke of Newcastle is said to have had seven boroughs “in his pocket”. In the 19th century measures began to be taken against rotten boroughs, notably the Reform Act of 1832 which abolished most rotten boroughs and spread parliamentary seats based on population, not past history of parliamentary representation. The introduction of the secret ballot helped prevent patrons from controlling districts, as they could no longer examine an individuals vote prior to its casting, electors as a result for the first time having the freedom to cast votes as they, not their landlord, wished.

Today, “rotten borough” is sometimes used to refer to a parliamentary constituency in which one particular political party has such massive support that its candidate is effectively uncontested. It is also used to refer to allegedly corrupt branches of local government – Private Eye has a column entitled Rotten Boroughs which lists stories of municipal wrongdoing.

A pocket borough was a parliamentary constituencies owned by one man who was known as the patron. Since the patron controlled the voting rights, he could nominate the two members who were to represent the borough. Some big landowners owned several pocket boroughs. For example, at the beginning of the 18th century, the Duke of Devonshire and Lord Darlington both had the power to nominate seven members of the House of Commons. Others, like Lord Fitzwilliam and Lord Lonsdale had even more seats under their control. All these men also had seats in the House of Lords.

Even those in favour of parliamentary reform had to to accept this system in order to be elected to the House of Commons. Henry Brougham developed a reputation as a lawyer with progressive views. This brought Brougham to the attention of the leaders of the Whigs. One of the Whig aristocrats, the Duke of Bedford, offered Brougham, the parliamentary seat of Camelford. The constituency only had thirty-one voters and they were all under Bedfords control. In 1812 Bedford sold Camelford to the Earl of Darlington for ?32,000. Brougham, who represented the constituency, now had to find another seat. Four years later the Duke of Bedford sold another one of his seats, Okehampton in Devon, to Albany Savile for ?60,000.

Men in favour of parliamentary reform were often forced to represent pocket boroughs. Sir Philip Francis the MP for Appleby wrote to a friend describing how had been “unanimously elected by one elector to represent the ancient borough of Appleby… there was no other candidate, no opposition, no poll demanded.” He added that “on Friday morning I shall quit this triumphant scene with flying colours and a noble determination not to see it again in less than seven years.”

The right to vote in Dorchester had been granted to all people who paid church and poor rates. The 6th Earl of Shaftesbury owned only half of the 408 houses in the town. To make sure he always controlled the constituency, the Shaftesbury leased out derelict plots of land to his friends during elections. This gave them the vote and guaranteed that Shaftesburys candidates always won. This including his son, Anthony Ashley Cooper, who inherited his fathers title in 1851.

Other political reformers such as Sir Francis Burdett also entered parliament in this way. In 1797 Burdetts wealthy father-in-law Thomas Coutts purchased the borough of Boroughbridge in Yorkshire from the Duke of Newcastle for ?4,000. Coutts gave the seat to his son-in-law and later that year Francis Burdett became a member of the House of Commons.

Prospective members of the House of Commons used a variety of different methods to persuade people to vote for them. Some gave money or gifts while others offered them jobs. This could be an expensive business. Sir Francis Burdett left the pocket borough of Boroughbridge and decided to stand for the more democratic Middlesex seat. He was elected for Middlesex in 1802, but was defeated in the elections held in 1804 and 1806. It has been estimated that Burdett spent ?100,000 during these two elections.

In Wooton Basset there were 309 eligible votes and the account books of the boroughs patron, Joseph Pitt show that he was having to pay them from 20 to 45 guineas a head to guarantee they would vote for his two candidates. Other patrons used threats rather than bribes. A wealthy landowner might warn tenants that they would be evicted if they did not vote for his candidate. People such as shopkeepers, trades people, solicitors and doctors were sometimes threatened with an organised boycott of their business if they did not do as they were told.

At the General Election in January, 1910, the seat was vainly contested by Viscount Wolmer, Mr. Seddon being returned by a majority of 752; but, at the election in December of the same year, Newton reverted to its former allegiance, and returned Viscount Wolmer by a. majority of 144.

SOUTH LANCASHIRE ELECTION, 1844.-The nomination of the candidates for this division took place at Newton in the Willows, on a temporary hustings erected in front .of the church and facing the Horse and Jockey Inn. There were present about 4,000 persons. W. Brown, Esq., was the Free-trade candidate, and Mr. Entwistle the Tory candidate. After the candidates had addressed the electors, a show of hands was taken, which resulted in favour of Mr. Entwistle. A poll was demanded, and the contest closed with a majority of 573 for Mr. Entwistle. A total of 14,458 votes was recorded at Newton, Ashton-under-Lyne, Bolton, Bury, Manchester, Old-ham, Rochdale, Liverpool, Ormskirk, and Wigan.

The Newton Division comprises the townships and parishes of Ashton, Billinge, Burtonwood, Eccleston, Golborne, Hay-dock, Newton, Poulton-with-Fearnhead, Rainford, Rainhill, Rixton-with-Glazebrook, Sankey, Winwick, Woolston-with-Martinscroft, and the freeholders of St. Helens and War?rington, and numbers 15,069 electors.

| Date | Candidate |

|---|---|

| 7 Jan. 1559 | SIR GEORGE HOWARD |

| RICHARD CHETWODE | |

| 1562/3 | FRANCIS ALFORD |

| RALPH BROWNE I | |

| 1571 | ANTHONY MILDMAY |

| RICHARD STONELEY | |

| 1572 | JOHN GRESHAM |

| JOHN SAVILE I | |

| 1584 | ROBERT LANGTON 1 |

| EDWARD SAVAGE 2 | |

| 8 Oct. 1586 | ROBERT LANGTON |

| EDWARD SAVAGE | |

| 14 Oct. 1588 | EDMUND TRAFFORD II |

| ROBERT LANGTON | |

| 1593 | EDMUND TRAFFORD II |

| ROBERT LANGTON | |

| 1597 | WILLIAM COPE 3 |

| GEOFFREY OSBALDESTON 4 | |

| 15 Oct. 1601 | THOMAS LANGTON |

| RICHARD ASHTON |

Newton – a little poor market’ Leland called it – first sent Members to Parliament in 1559. No authority has been found for its enfranchisement, but its first Members were not challenged in the House. The 1559 return is to testify that we, the free men of the borough of Thomas Langton, knight, baron of Newton … have elected Sir George Howard and Richard Chetwode Esquire, with the assent of the burgesses, to Parliament.The return was signed by Sir Ambrose Cave, chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster, and by William Fleetwood I, the -steward of the said borough’. Fleetwood had many connexions with the duchy and in addition was related to the Langtons. This last fact probably explains why the duchy picked on Newton when it set out to obtain the enfranchisement of an extra borough.

The names of the first two Members indicate that if Cave and Fleetwood were responsible for the enfranchisement of the borough, the deal was concluded through Sir William Cecil, who was given in return the nomination of the 1559 MPs. One of them was the brother of Queen Catherine Howard, Queen Elizabeth’s cousin no less. The other described Cecil as his -dear father’, and Cecil’s interest in him is apparent from his noting -Mr. Chetwood’s case’ as a subject for attention the day after Elizabeth’s succession. Francis Alford (1563) also had connexions with Cecil, but here the resemblance between 1559 and 1563 ends, for the second 1563 Member, Ralph Browne, was a protégé of Cave, whose will he witnessed (unless, of course, there is confusion here with another man of the same name). Both 1571 men were connected with the Exchequer, Anthony Mildmay through his father Sir Walter, and Richard Stoneley through the new chancellor of the duchy Sir Ralph Sadler. John Savile I (1572) had a connexion with the duchy and John Gresham (1572) with William Fleetwood I. The influence of the duchy now came to an end, for by 1584 the grandson and heir of Sir Thomas Langton (d. 1569) was of age, and for the rest of the reign he chose the Members, with the single exception of William Cope (1597) who seems to have owed his seat to Cecil. The Langtons were Catholics, though Robert (1584, 1586) conformed, and Thomas Langton himself did not sit while he owned the borough. In 1594, however, he sold it to the Fleetwoods with -the nomination, election and appointment of two burgesses of the Parliament’.

In 1601, when Langton needed to avoid his creditors, he arranged to be returned. The other 1601 MP was the steward of the borough. By this time Newton had a second borough official in the bailiff, who acted as returning officer.5

| Date | Candidate |

|---|---|

| 3 Mar. 1604 | SIR JOHN LUKE |

| RICHARD ASHTON | |

| c. Mar. 1614 | WILLIAM ASHTON II |

| Roger Charnock | |

| 4 Jan. 1621 | SIR GEORGE WRIGHT |

| RICHARD KIPPAX | |

| 17 Jan. 1624 | THOMAS CHARNOCK |

| EDMUND BRERES | |

| 6 May 1625 | SIR MILES FLEETWOOD |

| HENRY EDMONDES | |

| c. Jan. 1626 | SIR MILES FLEETWOOD |

| HENRY EDMONDES | |

| 29 Feb. 1628 | SIR HENRY HOLCROFT |

| SIR FRANCIS ANNESLEY , bt. |

Newton, a small market town near Wigan, appeared in the Domesday book as one of the townships in the -fee of Makerfield’, lying within Winwick parish in West Derby hundred, and was often named Newton-in-Makerfield or Newton le Willows.1 Although it received charters for a market and a fair in 1257 and 1301, it was never incorporated.2 Courts leet were held by the bailiff and steward, both of whom were appointees of the lord of the manor, who was formally known as the -baron’ of Newton. The bailiff, and perhaps also the steward, served as returning officers.3 Members had first been sent to Parliament in 1559 as a result of pressure from the duchy of Lancaster. The then steward, William Fleetwood†, a duchy official and later recorder of London, was distantly related to the -baron’ of Newton, Sir Thomas Langton (d.1569).4 Langton’s descendants sold the lordship of the manor in 1594 to another branch of the Fleetwood family, and with it the right of -nomination, election and appointment of two burgesses to the Parliament’. However, the terms of the sale did not take effect until the death of Thomas Langton† on 20 Feb. 1604.5 Langton’s successor was Sir Richard Fleetwood of Colwich, Staffordshire and Penwortham in Lancashire, who served as lord of Newton throughout this period.6 The franchise was vested in the freemen, around a dozen of whom regularly signed Newton’s election indentures.7 Despite its role in Newton’s early electoral history, the duchy of Lancaster had lost all influence by the middle of Elizabeth’s reign. Between 1604 and 1626 Members were chosen by Fleetwood or his cousin Sir Miles Fleetwood* without apparent reference to the chancellor of the duchy, and in 1628 the -baron’ shared his right of nomination with his son. It is unlikely that Newton was wealthy enough to pay wages to its parliamentary representatives during this period.

The election held in March 1604 took place less than three weeks before the opening of the session, and was perhaps delayed by Langton’s death and his replacement by Fleetwood as lord of the manor. Sir John Luke was awarded the first seat but may not have been the first choice, as his name on the indenture appears over an erasure. A Hertfordshire man who later sat for St. Albans, Luke was connected by marriage to both the chancellor of the duchy, Sir John Fortescue*, and to Sir Miles Fleetwood.8 The second seat went to the borough’s steward, Richard Ashton, who had previously sat in 1601. It is not clear whether he returned himself, but if he did his eligibility went unquestioned.

In 1614 one seat was conferred on Ashton’s younger son, William, while the other went to Roger Charnock, a local lawyer whose stepmother was Sir Richard Fleetwood’s aunt. Charnock and his elder brother Thomas, who sat for Newton in 1624, were linked to the Fleetwoods both professionally and financially. They also shared with them many of the same connections, as a result of their marriages into various Lancashire families known for their adherence to Catholicism. Fleetwood himself was one of several crypto-Catholic members of the Lancashire gentry who bought baronetcies in 1611.9

The first seat in 1621 went to Sir George Wright, of Richmond in Surrey, the clerk of the Stables. He was possibly helped by Sir Miles Fleetwood, a client of the marquess of Buckingham, then master of the Horse. Sir Miles, who twice represented the borough himself, wielded considerable influence over his cousin, and was responsible for the selection of at least three of the five outsiders who sat for Newton during the period. The second seat went to Sir Richard Fleetwood’s brother-in-law, Richard Kippax. Both Wright and Kippax spoke in the Commons on bills relating to matters of probate, which suggests that they might have been prompted to do so by their patron; certainly they had no other shared interest. Kippax also spoke on the Irish cattle bill, which was surely of interest to Fleetwood, who owned extensive lands in Munster and Cork.10

In 1624 two local men were elected, both of whom had close ties with Sir Richard Fleetwood and each other: Thomas Charnock of Astley, and Edmund Breres, a Gray’s Inn lawyer and native of Preston. Breres had persuaded Fleetwood and Charnock to act as sureties for loans he could not repay.11 He and Charnock therefore sought entry to Parliament as a means of obtaining protection from Breres’ creditors.

In the first and second Caroline parliaments the patronage of the borough appears to have been entirely dominated by Sir Miles Fleetwood, who allocated the first seat to himself on both occasions. The second seat went twice to Henry Edmondes, son of the privy councillor and treasurer of the Household Sir Thomas Edmondes*. Sir Richard Fleetwood emigrated to Ireland in around 1626, leaving his son Thomas in control of Newton.12 Thomas Fleetwood appeared as joint lord of the manor on the election indenture of 1628 though he was then aged only 19.13 Two officials in the Irish administration were returned, Sir Henry Holcroft and Sir Francis Annesley. Both may have come into contact with Sir Richard Fleetwood in Ireland; Annesley was also a client of Buckingham, and may have had links with Sir Miles Fleetwood, who was also developing his Irish interests at that time.14

- 1. J.H. Lane, Newton in Makerfield, i. 3-6.

- 2. CChR, ii. 1, iii. 2; VCH Lancs. iv. 132-6.

- 3. Lane, 9, 22; E. Baines, Hist. of Palatinate and Duchy of Lancaster ed. J. Croston, iv. 382-3, 391.

- 4. R. Somerville, Hist. of Duchy of Lancaster, i. pp. xiv, 319, 505-6.

- 5. Local Gleanings Relating to Lancs. and Cheshire ed. J.P. Earwaker, ii. 686; Lancs. IPMs ed. J.P. Rylands (Lancs. and Cheshire Rec. Soc. iii), 105-6.

- 6. VCH Lancs. i. 374-5; Wills and Inventories ed. G.J. Piccope (Chetham Soc. li), 246-55; Vis. Staffs. ed. H.S. Grazebrook, 129-30; R.W. Buss, Fleetwood Fam. of Colwich, Staffs. 3; Vis. Lancs. (Chetham Soc. lxxxii), 122.

- 7. C219/35/53; 219/37/138; 219/38/134; 219/39/126.

- 8. R.C.L. Sgroi, -The Electoral Patronage of the Duchy of Lancaster, 1604-28′, PH, xxvi. 322-3.

- 9. 47th DKR, app. 126; CSP Dom. 1641-43, p. 435.

- 10. Nicholas, Procs. 1621, i. 246; CJ, i. 615b, 650b.

- 11. DL1/285, 290, 291, 297, 299, 300; C2/Chas.I/F35/12; C2/Chas.I/F50/81.

- 12. M. MacCarthy-Morrogh, Munster Plantation: Eng. Migration to Southern Ire. 1583-1641, p. 195; E.T. Bewley, -Fleetwoods of Co. Cork’, Jnl. of Royal Soc. of Antiqs. of Ire. xxxviii. 103-25.

- 13. C219/41A/31.

- 14. E.T. Bewley, -An Irish Branch of the Fleetwood Fam.’, The Gen. n.s. xxiv. 217-41.

| Date | Candidate |

|---|---|

| c. Apr. 1660 | RICHARD LEGH |

| WILLIAM BANKS I | |

| 23 Apr. 1661 | RICHARD LEGH |

| JOHN VAUGHAN | |

| 24 June 1661 | SIR PHILIP MAINWARING vice Vaughan, chose to sit for Cardiganshire |

| 24 Oct. 1661 | RICHARD GORGES, Baron Gorges, vice Mainwaring, deceased |

| 28 Feb. 1679 | SIR JOHN CHICHELEY |

| ANDREW FOUNTAINE | |

| 11 Sept. 1679 | SIR JOHN CHICHELEY |

| ANDREW FOUNTAINE | |

| 1 Mar. 1681 | SIR JOHN CHICHELEY |

| ANDREW FOUNTAINE | |

| 23 Apr. 1685 | SIR JOHN CHICHELEY |

| PETER LEGH | |

| Thomas Brotherton | |

| 11 Jan. 1689 | SIR JOHN CHICHELEY |

| FRANCIS CHOLMONDELEY |

Although their chief residence was in Cheshire, the Leghs of Lyme enjoyed the principal property interest in Newton throughout the period, and in 1661 Richard Legh acquired the borough and manor from Sir Thomas Fleetwood. Thus not only were most of the burgages held by him, but the steward, who acted as returning officer, was chosen in his court leet.1

Legh’s royalist and Anglican sentiments are unquestionable, but he had sat for Cheshire under the Protectorate, and was therefore eligible at the general election of 1660. His colleague William Banks had married into another branch of the Legh family, and presumably sat on the same interest. Before the next election Legh himself married the daughter of (Sir) Thomas Chicheley of Cambridgeshire, who probably recommended the distinguished lawyer John Vaughan for the junior seat. When Vaughan chose to sit for his county, he was replaced by Sir Philip Mainwaring, the younger son of a Cheshire family who had sat in five Parliaments before the Civil War. Mainwaring died a few months later, and Chicheley was doubtless responsible for recommending another Cambridgeshire landowner, Lord Gorges.

Legh had seldom shown much enthusiasm for Westminster, and he retired at the dissolution of the Cavalier Parliament, though for the remainder of the period his brother Thomas Legh acted as returning officer. In the name of the -burgesses and commonalty’ he returned the patron’s brother-in-law, Sir John Chicheley, and Chicheley’s brother-in-law, Andrew Fountaine, to all three Exclusion Parliaments. Chicheley opposed the bill, but Fountaine voted for it, and was dropped in 1685 in favour of Legh’s 15-year-old heir Peter. This was almost too much even for so docile a constituency. Thomas Brotherton†, a Tory lawyer of Gray’s Inn whose family had held the Hey estate since at least 1573, was nominated by the free burgesses, though the Legh interest felt little alarm at his candidature: -he is likelier to be made lord mayor of London without ever leaving his borough of Newton as he calls it’. Local sportsmen, possibly unacquainted with the hurdles at Westminster, thought otherwise; odds of five to one were laid that Brotherton would be Member for Newton by the end of the session. He duly petitioned, presumably on the ground of Peter Legh’s age; but, like most petitions in James II’s Parliament, his never emerged from committee. Richard Legh died in 1687, and his son was too loyal to the Stuarts ever to stand after the Revolution. Chicheley had no such scruples, and he was accompanied in the Convention by Francis Cholmondeley, another younger son from Cheshire. Cholmondeley proved as staunch a Jacobite as Legh, and sought in vain to resign his seat after the transfer of the crown, since he could not take the oaths to the new regime. 2

| Date | Candidate | Votes |

|---|---|---|

| 11 Mar. 1690 | SIR JOHN CHICHELEY | 47 |

| GEORGE CHOLMONDELEY | 47 | |

| Thomas Brotherton | 20 | |

| Sir James Forbes | 192 | |

| 18 Dec. 1691 | JOHN BENNET vice Chicheley, deceased | |

| 31 Oct. 1695 | LEGH BANKS | |

| THOMAS BROTHERTON | ||

| 5 Aug. 1698 | THOMAS LEGH I | |

| THOMAS BROTHERTON | ||

| 13 Jan. 1701 | THOMAS LEGH I | |

| THOMAS BROTHERTON | ||

| 1 Dec. 1701 | THOMAS LEGH I | |

| THOMAS LEGH II | ||

| 27 July 1702 | JOHN GROBHAM HOWE | |

| THOMAS LEGH II | ||

| 31 Dec. 1702 | THOMAS LEGH I vice Howe, chose to sit for Gloucestershire | |

| 7 Dec. 1703 | JOHN WARD vice Legh I, deceased | |

| 12 May 1705 | THOMAS LEGH II | |

| JOHN WARD | ||

| 13 May 1708 | THOMAS LEGH II | |

| JOHN WARD | ||

| 19 Oct. 1710 | THOMAS LEGH II | |

| JOHN WARD | ||

| 3 July 1711 | JOHN WARD, re-elected after appointment to office | |

| 8 Sept. 1713 | JOHN WARD | |

| ABRAHAM BLACKMORE |

Newton was a small township in the south of Lancashire -consisting of about 150 houses’. The lordship of the manor of Newton had been held by the Leghs of Lyme, in this period headed by the non-juror Peter Legh†, since 1661, and the lord of the manor dominated the borough. The borough’s sole administrative body was the court leet which was held by the authority of the lord of the manor, and the court’s presiding officer, the steward, was directly appointed by him and held the post at his discretion, a fact of some importance as the steward also acted as the borough’s returning officer. The Leghs’ dominance of Newton was also based upon extensive landholdings in the area, which had been given physical expression in the 1680s with the construction of a new court house and chapel in the township at the family’s expense. By the middle of the 17th century the franchise had come to be exercised by the township’s 40s. freeholders holding land in fee simple by right of medieval indentures, known locally as charterers, or by leases for lives, or leases for years dependent upon lives. The large landholdings of the Leghs in Newton and the surrounding area meant that this development did not, however, rob the lord of the manor of his immense influence in the borough. The Leghs’ power at Newton was always, as one contemporary put it, -sufficient to influence an election according to their own minds’, but in the early 1690s their hold was less secure than a modern historian’s description of Newton as -the pocket borough par excellence‘ would indicate.3

The 1690 election saw the lawyer Thomas Brotherton revive his claim to a seat at Newton. Brotherton stood with the support of the county’s most prominent Whigs, most notably Lord Brandon (Charles Gerard*), and attempted to break the Legh stranglehold upon the borough by claiming that the franchise included under-tenants and those with leases for years, known locally as rackers, which Brotherton thought would increase the borough’s electorate from the 104 estimated by Legh’s agents to 167. Brotherton treated generously, and stood on a joint interest with Sir James Forbes in an effort to prevent the second votes of supporters going to either of Legh’s candidates, his uncle Sir John Chicheley and his cousin George Cholmondeley. Despite a brief wobble the confidence of the Legh interest was reaffirmed by a personal visit to the borough by Peter Legh, after which his kinsmen succeeded in comfortably defeating Brotherton and Forbes.4

Brotherton and Forbes were not, however, prepared to accept this defeat and immediately began preparations for a petition presented to the Commons on 25 Mar. Their case rested upon the claim that rackers were entitled to vote at Newton, citing the return of 1621 as evidence for this claim. In response Legh had set the Tory MP for Clitheroe, Roger Kenyon, to investigate this issue before the petition had been lodged. Kenyon’s researches proved that the return of 1621 did not support the petitioners’ contentions, but raised the spectre of another danger to the Legh interest. Kenyon reported that the return of 1621 was made by the majority of charterers, and pointed out the polling of other freeholders was -an innovation upon the privileges of the borough set up in the late wars, in Oliver’s time’. Peter Legh’s uncle Thomas† pointed out that if this narrower franchise were to be restored the Legh interest at Newton could be placed in jeopardy. As charterers tended to be more substantial individuals than the other Newton freeholders, he feared that if Kenyon’s discoveries became public knowledge it could lead to the charterers feeling that they -can choose one or both burgesses at any time the writs come out’ without reference to the lord of the manor. Thomas Legh also warned that even if the charterers were not interested in usurping the Legh interest in the borough other dangers remained, such as the prospect that men with money to spare and a desire for influence could more easily -court’ the select band of charterers than the larger body of freeholders in order to draw them away from the Legh interest. Given these possibilities, it comes as no surprise that the defence against the petition made no mention of this narrow definition of Newton’s franchise, claiming instead that the franchise lay with the charterers and freeholders with leases for lives, or years determinable upon lives. Brotherton alone renewed the petition on 6 Oct., and he continued treating in the borough, keeping the spirits of his supporters up with reports of imminent success, and a brief flurry of excitement accompanied September’s false rumours that Cholmondeley had died while serving with the army in Ireland. In May 1691 the situation was complicated by the death of Chicheley and consequent canvassing for the prospective by-election. John Bennet, the brother of the rector of Winwick, the parish of which Newton was part, began to lobby for Legh’s support at the by-election, proclaiming that -one of my greatest designs is to oppose Mr. Brotherton’. Peter Legh’s uncle Thomas wrote to him regarding Bennet’s candidacy, stating that -your best friends in these parts mightily desire it, among which I am one’, and when the 9th Earl of Derby wrote to assure Legh that Bennet -has friends in the House of Commons and money too perhaps sufficient to cope with Brotherton’, Legh yielded to Bennet’s applications. Brotherton soon gave notice of his intention to contest the by-election, and Legh feared that -the matter may go but ill; for not one stone does he leave unturned’. Brotherton was thus proceeding upon two fronts, having renewed his petition again on 22 Oct. 1691, until on 2 Dec. he withdrew his petition to allow the writ for the by-election to be issued. The withdrawal of the petition appears to have been the product of Brotherton’s realization that his attempts to gain a seat at Newton were doomed to failure, for despite treating at Newton he was unable or unwilling to pursue the contest to a poll, and Bennet was returned unchallenged.5

The election of 1695 was dominated by the long shadow of Peter Legh’s alleged involvement in the Lancashire Plot in 1693–4. Legh had been accused of receiving a Jacobite commission from the Earl of Middleton (Charles†), and consequently imprisoned, first in London and then in Chester, until the collapse of the crown’s case at the Manchester trials of October 1694 led to his acquittal at Chester the same month. During his trial he had, however, incurred obligations which limited his actions in choosing candidates for Newton. The prominent roles taken by Legh’s cousin Legh Banks, whose evidence played a key role in discrediting the allegations against the supposed Jacobite plotters, and Brotherton, whose rehabilitation in Lancashire’s Tory circles was completed by his representing the accused at Manchester, left Legh feeling obliged to support them at Newton in this election. Legh dropped Bennet, who appears to have gone quietly, and Cholmondeley, a far less willing sacrifice, and felt obliged to reject applications from several other individuals. Having been forced out of contention at Clitheroe, Kenyon applied to Legh for a seat, asking for support for both himself and Legh’s uncle Sir John Ardern of Harden, only to be told that Legh had -fixed upon two for Newton without any room for either of us’, which Legh blamed upon his -unfortunate circumstances’. Legh was also forced to turn down the appeal of Sir Thomas Grosvenor, 3rd Bt.*, who was facing a bitter struggle to retain his seat at Chester, pleading that -I am engaged to some friends to honour them with my interest at Newton’, and the requests of his maternal great-uncle for a seat for the Irish MP Sir James Shaen. Legh’s candidates were returned unchallenged, as were all those he supported at the remaining elections in this period.6

The 1698 election passed with less controversy, despite fears that Brandon (now Earl of Macclesfield), would attempt to disrupt Legh’s hold upon the borough. The only disturbance to the return of Brotherton and Legh’s cousin Thomas Legh I came with the unsuccessful request for a seat on behalf of Thomas Done, a Tory squeezed out of his former seat in Newtown, Isle of Wight. Despite a request in late 1699 for Legh’s support at Newton in any forthcoming election on behalf of Edward Brereton, the Member for Denbigh Boroughs, and a similar request in November 1700 from Richard Bold*, Brotherton and Legh were again returned without undue trouble in January 1701.7

The following month the newspapers mistakenly announced Brotherton’s death after a bout of fever. Lord Stanhope wrote to Thomas Coke* suggesting he might succeed Brotherton at Newton: -Mr Legh of Lyme has it in his power to put in who he will in his room. If you care to condescend so far as to accept of it, I know I can get it done for you, without your coming down or giving yourself the least trouble in the matter.’ Legh, however, thought that Coke should attend the election -to prevent some sort of censure that formerly had been made that Newton Members seldom were known to the voters . . . so that I would not give them the least reason, at this time, to frame a story or to make the least division amongst us’. Fortunately, given Brotherton’s recovery from illness, Coke showed -no great inclinations of standing’. The second election of 1701 saw Legh’s brother Thomas II replace Brotherton as one of Newton’s representatives, though Brotherton appears to have been given some indication that he would be returned again in an ensuing election.8

Upon Anne’s accession Newton despatched a humble address reflecting the Toryism of both its patron and MPs, declaring the borough’s -utter detestation and abhorrence of that spirit of blasphemy and profaneness, schism and sedition, which has of late so insolently showed itself’, and assuring Anne that -from the bottom of our hearts we must cheerfully recognise your Majesty our hereditary and lawful sovereign’, pledging that -we will to the utmost of our power support and assist your Majesty against all attempts which may endanger your royal person or government, our most excellent Church or the protestant succession’. The 1702 election saw Newton being used as an electoral haven for the Tory John Grobham Howe. Having been defeated at Gloucestershire in November 1701, Howe chose to approach Peter Legh, through the Earl of Nottingham (Daniel Finch†), for his support at Newton lest he fail in his campaign to regain his county seat. Legh concurred in this proposal, provided -it may not be known till the time of the election lest the faction may endeavour to make divisions in his town which may occasion him trouble hereafter’. He accepted that, should Howe gain a seat at Gloucestershire, he would sit for his county rather than for Newton, and expressed the hope that a double return could be avoided by Howe securing election for knight of the shire before the Newton writ was issued. News of Howe’s success in Gloucestershire came too late, however, to avoid his return for Newton, along with Thomas Legh II. After defeating a petition against his return Howe opted to sit for the county, though he had written to Peter Legh on hearing of his election at Newton to express -my due acknowledgements for so great an honour’. A writ for a new election was issued on 20 Nov., and forecasts that Thomas Legh I would -spring from the root again’ proved to be accurate, though a fatal accident in March 1703 meant that his return to parliamentary service was short-lived. Legh decided to support the Tory lawyer John Ward III at the by-election in December, and his return was unopposed. An address from Newton registering approval of Ward’s and Legh’s parliamentary behaviour was prepared, though not sent, in 1705, expressing appreciation for their support of -that excellent bill brought in to prevent that scandalous practice of occasional conformity . . . for their courageous maintaining the liberties and the privileges of the Commons of England in the case of the Ailesbury [sic] men . . . [and] what they have done in order to prevent the mischiefs which may arise to this nation from several pernicious Acts lately passed in Scotland’. Needless to say, and despite the idea being mooted that Thomas Legh II should stand down in order to pursue a place to ease his almost constant money worries, the two sitting Members were again returned without opposition in 1705.9

The borough remained undisturbed in the three years to the next election, when Peter Legh again nominated his brother and Ward. Neither candidate attended the court of election, and the borough steward was forced to deliver the following speech in an attempt to quell any mutterings among the populace about such neglect:

we are to proceed to the election of two burgesses to represent this borough in the ensuing Parliament. I can say without flattery you have been more unanimous and discreet in your elections for many years than any borough or corporation in the country. And the reason of this is plain, you are all members of the Church of England, there are no schisms nor factions amongst you, nor do any base or mean principles prevail amongst you . . . as to the gentlemen who served you in the last Parliament and who offer themselves again to serve you in this, all I shall say is that they served you faithfully and ingeniously. They are well affected to the Queen and government. They are neither soldiers nor pensioners and therefore fitter to be trusted with our Church and estates. In one word they are then after our own hearts and therefore (if you please) let us now proceed to elect and return them.

The recipients of this stirring address proceeded to do just as they were asked, a return that was repeated in 1710.10

When Ward was appointed to the Welsh judiciary in 1711 he was returned unopposed at the ensuing by-election, but the passage of the Qualification Act the same year meant that the financially embarrassed Thomas Legh II decided, with his brother’s support, to approach the Earl of Oxford (Robert Harley*) for a place to relieve his money worries, in return for allowing Oxford to nominate Legh’s successor at Newton. Negotiations were under way from summer 1711, and in August 1713 Ward was returned for Newton in partnership with Oxford’s nominee, Abraham Blackmore. Legh noted that Blackmore’s return had caused -some unexpected grumbles amongst us’, and though he was confident that -it signifies nothing’ Blackmore himself noted a certain -uneasiness’ in the borough at his return, an uneasiness which was to manifest itself in unfounded rumours of a challenge at the next election. Following the difficulties Peter Legh had faced in the early 1690s he had established a level of control at Newton which, while needing tending and attention to the feelings of the Newton’s inhabitants, ensured that his family maintained their control of the borough’s parliamentary representation.11

- 1. John Rylands Univ. Lib. Legh of Lyme mss muniments box Y bdle. B, call bk., c.1690.

- 2. Legh of Lyme mss muniments box Z bdle. B, pollbk., c.11 Mar. 1690.

- 3. Bodl. Willis 46, ff. 361, 420; 31, ff. 69, 76; VCH Lancs. iii. 375; Cheshire RO, Leicester-Warren mss DLT/C35/85, Peter Legh to Sir Francis Leicester, 3rd Bt.†, 11 Jan. 1732; Legh of Lyme muniments box Z bdle. B, acct. of Newton election, 1685, call bk., c.1690, counter-petition of George Cholmondeley and Sir John Chicheley, c.1690, [Roger Kenyon] to [Legh], 16 Mar. 1689–90; Legh of Lyme mss corresp., Thomas Legh† to same, c.1690; HMC Cowper, ii. 421; W. A. Speck, Whig and Tory, 57.

- 4. Lancs. RO, Kenyon mss DDKe 9/63/7, Thomas Legh to Kenyon, 2 Mar. 1690; Legh of Lyme mss muniments box Z bdle. B, -A copy of those Brotherton calls voters in Newton’, c.1690, pollbk. 11 Mar. 1690; box Y bdle. B, call bk., c.1690; Legh of Lyme mss corresp. George Cholmondeley to Visct. Cholmondeley, c.1690.

- 5. Legh of Lyme mss muniments box Z bdle. B, counter-petition of Chicheley and Cholmondeley, c.1690, [Kenyon] to [Peter Legh], 16 Mar. 1689–90; Legh of Lyme mss corresp., Thomas to Peter Legh, c.1690, 6 Sept. 1690, 24 May 1691, Legh Bowden to same, 28 Sept. 1690, Richard Edge to Bowden, 21 May 1691, Peter Legh to [?], 2 June 1691, Derby to Peter Legh, 2 June 1691; NLW, Chirk Castle mss E1073, Bennet to Sir Richard Myddelton, 3rd Bt.*, 21 May 1691.

- 6. HMC Kenyon, 363–7, 384–5, 387–94; Eg. 720, ff. 79–80; Legh of Lyme mss corresp., Francis Cholmondeley† to Peter Legh, 29 Sept., 12 Oct. 1695, Brotherton to same, 10 Oct. [1695], 12 Oct. 1695, Thomas Bankes to same, c.1695, 8 June 1695, Legh to Visct. Cholmondeley, c.1695, Kenyon to Legh, 19 Oct. 1695, Grosvenor to same, 15 Oct. 1695, Sir James Shaen to Sir William Russell, 24 Sept. 1695, Russell to Elizabeth Legh, 8 Oct. 1695, same to Peter Legh, 22 Oct. 1695; Lyme Letters ed. Lady Newton, 323; Add. 36913 ff. 232, 235.

- 7. Legh of Lyme mss corresp., Bowden to Peter Legh, 22 July 1698, Francis Cholmondeley to same, 23 Aug. 1699, Bold to same, 27 Nov. 1700; Greater Manchester RO, Legh of Lyme mss E17/89/40/10, [?] to [Legh], 7 July 1698.

- 8. BL, Lothian mss, Stanhope to Coke, c.1701; HMC Cowper, ii. 421–2.

- 9. Legh of Lyme mss muniments, box Z bdle. B, Newton address, c.1702, Howe to [Peter Legh], 22 Aug. 1702; box Y bdle. C, Newton address, c.1705; Legh of Lyme mss corresp., Francis Cholmondeley to same, 11 Dec. 1703, Thomas Legh II to same, 22 Aug. 1704, 24 Apr. 1705; G. Holmes, Pol. in Age of Anne, 319; Add. 29588, ff. 68–69, 74–78, 109–10, 140–1; 70020, f. 120; Cheshire RO, Arderne mss DAR/F/33, Samuel Daniell to [?], 31 July 1702.

- 10. Legh of Lyme mss corresp. Edward Allanson to Ward, 13 May 1708.

- 11. Add. 70201, Thomas Legh II to Oxford, 28 June 1711, 7 July 1712; Add. 70237, Edward Harley* to same, 26 Sept. 1713; Legh of Lyme mss corresp., Peter Legh to Ward, c.21 Aug. 1713; Legh of Lyme mss muniments box Z bdle. B, Ward to [Edward Allanson], 28 Aug. 1713, Blackmore to same, 4 Mar. 1713[–14]; box Y bdle. B, same to Thomas Legh, 11 Mar. 1713[–14]; Greater Manchester RO, E17/89/1/7, Leicester to Peter Legh, 3 Feb. 1714[–15].

| Date | Candidate |

|---|---|

| 7 Feb. 1715 | SIR FRANCIS LEICESTER |

| WILLIAM SHIPPEN | |

| 27 Mar. 1722 | SIR FRANCIS LEICESTER |

| WILLIAM SHIPPEN | |

| 22 Aug. 1727 | LEGH MASTER |

| WILLIAM SHIPPEN | |

| 29 Apr. 1734 | LEGH MASTER |

| WILLIAM SHIPPEN | |

| 8 May 1741 | LEGH MASTER |

| WILLIAM SHIPPEN | |

| 15 Dec. 1743 | PETER LEGH vice Shippen, deceased |

| 1 July 1747 | PETER LEGH |

| SIR THOMAS EGERTON |

Newton, a proprietary borough, was under the absolute control of the Leghs of Lyme who held the barony and nominated the returning officers.2 In 1715 the proprietor was Peter Legh, a non-juror,3 who returned Tory friends and members of his family till his death in 1744, when it passed to his nephew and heir, Peter Legh.

| Date | Candidate |

|---|---|

| 17 Apr. 1754 | Peter Legh |

| Randle Wilbraham | |

| 30 Mar. 1761 | Peter Legh |

| Randle Wilbraham | |

| 19 Mar. 1768 | Peter Legh |

| Anthony James Keck | |

| 11 Oct. 1774 | Anthony James Keck |

| Robert Vernon Atherton Gwillym | |

| 12 Sept. 1780 | Thomas Peter Legh |

| Thomas Davenport | |

| 30 May 1783 | Legh re-elected after appointment to office |

| 6 Apr. 1784 | Thomas Peter Legh |

| Sir Thomas Davenport | |

| 10 Apr. 1786 | Thomas Brooke vice Davenport, deceased |

Newton was a pocket borough of the family of Legh of Lyme Park. As lords of the manor they appointed the steward and the bailiff (the returning officers), and in this period had complete control of the corporation.

| Date | Candidate | Votes |

|---|---|---|

| 21 June 1790 | THOMAS PETER LEGH | |

| THOMAS BROOKE | ||

| 30 May 1796 | THOMAS PETER LEGH | |

| THOMAS BROOKE | ||

| 15 Sept. 1797 | THOMAS LANGFORD BROOKE vice Legh, deceased | 39 |

| Peter Patten | 37 | |

| PATTEN vice Brooke, on petition, 13 Dec. 1797 | ||

| 6 July 1802 | THOMAS BROOKE | |

| PETER PATTEN | ||

| 3 Nov. 1806 | THOMAS BROOKE | |

| PETER HERON | ||

| 8 May 1807 | PETER HERON | |

| JOHN IRELAND BLACKBURNE | ||

| 8 Oct. 1812 | PETER HERON | |

| JOHN IRELAND BLACKBURNE | ||

| 16 Apr. 1814 | THOMAS LEGH vice Heron, vacated his seat | |

| 18 June 1818 | THOMAS LEGH | |

| THOMAS CLAUGHTON |

Newton was controlled by the Leghs of Lyme, who were lords of the manor and also owned most of the land in the borough. The head of the family until his death in 1792 was Peter Legh, and the Members returned in 1790 and 1796 were his nephew and heir, Thomas Peter Legh, and Thomas Brooke of Ashton Hayes, who was second cousin to Thomas Peter. The latter died in 1797, having bequeathed the family property to his eldest illegitimate son Thomas Legh, then about four years old. There was a contest for the vacant seat between Peter Patten, eldest son of Thomas Patten of Bank Hall and first cousin of Thomas Brooke, and Thomas Langford Brooke of Mere, whose father Peter had married as his first wife Thomas Peter Legh’s cousin Anne. Seven years later Patten, who was also distantly related to the Leghs, told Canning that he had stood for Newton -on the grounds of alliance’ with the deceased Member’s family and that -my claims were warmly supported by his executors in opposition to their own family interest’, which might have disposed them to support Brooke.1 The latter secured a majority of two, but Patten and two electors petitioned, alleging that illegal votes tendered for Brooke had been admitted, that good votes for Patten had been rejected and that Brooke had resorted to extensive bribery and corruption. The election committee decided that the merits of the case rested partially on the right of election. Counsel for the sitting Member submitted that it was -in persons having an estate of freehold, or for a term, or residue of a term of 99 years or upwards, determinable on one or more life or lives, in any messuages, lands, or tenements, within the borough’. Counsel for Patten asserted that the franchise was

exclusively vested in the freemen or burgesses … that is to say, in any person seised of an estate of freehold, in any house, building, or lands, within the borough, of the value of forty shillings a year and upwards; and, in case of joint-tenants, or tenants in common, no more than one person has a right to vote for one and the same house or tenement.

The committee ruled that neither submission was correct, but determined the right of election to be as that submitted on behalf of Patten, with the addition of the word -corporeal’ (that is real, tangible property as opposed to legal rights connected with property) before -estate of freehold’. Brooke, who had clearly been trying to widen the franchise, immediately gave up, informing the electors that the -very unexpected determination’ on the right of election made it impossible for him to produce a majority of legal votes before the committee. He hoped at a future election again to -stand forth in defence of that independence and freedom of election you have so nobly endeavoured to assert’, but never did so.2

Newton was therefore remarkable for the fact that, having returned Members since 1558, there was no formal determination of its right of election until within 25 years of its disfranchisement in 1832.3 The effect was to confirm the power of the Leghs, and on 25 Aug. 1806 Charles Williams Wynn told his uncle:

I find upon inquiry that the borough of Newton is so entirely in the hands of the trustees of the late Mr Legh’s property during the minority of his son that it is scarcely possible that any contest should take place.

He added that Thomas Brooke had considered retiring at the next election in favour of his nephew Sir Richard Brooke of Norton Priory, who had just come of age.4 Nothing came of this and it was Patten who stood down. He was replaced by Peter Heron of Moor Hall, who was first cousin once removed of Thomas Langford Brooke and whose uncle, as one of the trustees of the Legh property, had supported Patten in the 1797 contest. In 1807 Thomas Brooke made way for his sister’s nephew John Ireland Blackburne, son of one of the county Members, who was also distantly related to the Leghs. When Thomas Legh came of age in 1814 Heron vacated for him, and in 1818 Legh brought in his brother-in-law, Thomas Claughton, in place of Blackburne.

| Date | Candidate |

|---|---|

| 9 Mar. 1820 | THOMAS LEGH |

| THOMAS CLAUGHTON | |

| 11 Feb. 1825 | SIR ROBERT TOWNSEND TOWNSEND FARQUHAR, bt. vice Claughton, vacated his seat |

| 9 June 1826 | THOMAS LEGH |

| THOMAS ALCOCK | |

| 31 July 1830 | THOMAS LEGH |

| THOMAS HOULDSWORTH | |

| 30 Apr. 1831 | THOMAS LEGH |

| THOMAS HOULDSWORTH |

Newton was a small manufacturing town with one main street, five miles from Warrington and seven from Wigan. It had no corporation and was governed by the borough steward and the bailiff of the manor, who held a court baron and court leet three times a year and were the returning officers.2 The electorate had been deliberately reduced in number and it remained under the complete control of Thomas Legh of Lyme, Cheshire, the lord of the manor, who owned most of the property in the borough, including his residences at Haydock Lodge and Golborne Park. The franchise had been defined by an election committee in 1797 as being in -any person seised of a corporeal estate of freehold in any house, building, or lands, within the borough, of the value of forty shillings a year and upwards; and in case of joint-tenants, or tenants in common … no more than one person has a right to vote for one and the same house or tenement’.3 Newton was in effect a burgage borough.

In 1820 Legh, who returned himself throughout the period, again brought in his brother-in-law Thomas Claughton, a salt manufacturer, lawyer and land speculator possessed of certain local properties. Claughton resigned as a bankrupt in 1825 and was replaced, presumably as a paying guest, by Sir Robert Townsend Farquhar, the former governor of Mauritius. At the general election of 1826 Legh returned Thomas Alcock, a wealthy Surrey landowner, and in 1830 and 1831 Thomas Houldsworth of Sherwood Hall, Nottinghamshire, a Manchester cotton spinner who had previously represented Pontefract. It was alleged in 1830 that he was a creditor of Legh, given the seat in compensation for his money.4 He was certainly a shareholder in the locally controversial schemes, 1830-2, for a Wigan-Newton-Warrington railway.5

The Grey ministry’s reform bills proposed the disfranchisement of Newton, which was ranked 34th in the revised list of boroughs in late 1831, with 274 houses and £151 received in assessed taxes.6 Enquiries that December revealed that the borough encompassed 50 acres in a parish (Winwick) of 2,644, and had no freemen. The steward John Fitchett and bailiff Richard Owen, however, added:

Neither do we consider this to be in fact the main object of the inquiry in the present instance; but rather to ascertain whether there be any difference in between the extent of the borough and the township within which the same is situate, which term in the eight northern counties is synonymous, or in general of similar import to the division of -parish’ in southern counties. In this case there is not any difference between the borough and township of Newton, which are co-extensive.7

Its extinction under the revised reform bill was confirmed by the Commons on 20 Feb. 1832. The Lords carried an amendment substituting Newton for Wigan as the election town for Lancashire South (by 54-5), 7 June 1832. It remained a municipal borough until 1835.8

- 1. PP (1831-2), xxxvi. 559.

- 2. E. Baines, Hist. Lancs.(1824), ii. 433; J.P. Earwacker, E. Cheshire, ii. 161-3; PP (1831-2), xxxvi. 47.

- 3. CJ, liii. 147.

- 4. Leeds Mercury, 24 July 1830.

- 5. LJ, lxiii. 260, 927, 959, 1058.

- 6. PP (1831-2), xxxvi. 27, 47.

- 7. Ibid. 559; LJ, lxiv. 357.

- 8. PP (1835), xxvi. 741.

Transcribed from various sources by Steven Dowd for use in the Newton le Willows website ©2005