BY T. C. BARKER, M.A. Read 16 December 1948

When Arthur Young visited the north of England in 1771 he went “to Manchester with design not only to view the manufactures of that town but to make it my headquarters from thence to go the tour of his Grace the Duke of Bridgewater’s navigation about which such wonders are abroad.” (1)

In the account of his tour in the north Young devoted forty- six pages, complete with maps and diagrams, to a description of these wonders: the twelve sets of “canal doors”, the underground tunnel deep into the hillside at Worsley and the aqueduct over the Irwell at Barton were all greeted with excited enthusiasm.

Young’s description, Smiles’s appealing character sketch of James Brindley(2), and the reputation which the Bridge water Canal gained by its magnificence, have together caused some historians, following Young’s example,(3) to concentrate their attention upon the Worsley-to-Manchester Canal at the expense of the Sankey Navigation. Professor Mantoux, for instance, wrote that the Worsley Navigation was “the first real canal in England” (4), a belief which has received further wide publicity from Dr. Trevelyan in his English Social History(5) and, very recently, from Professor Ashton.(6) Other writers have taken advantage of the fuller information which was available for the Worsley Canal and have passed over the Sankey Navigation with a few, often puzzling, remarks.(7) Jackman, in his large, two- volume work, Transportation in Modern England, dismissed it in four brief lines.(8)

There is little or no excuse for this tendency to ignore the Sankey Navigation and to stress the chronological priority of the Bridgewater Canal, the first part of which (from Worsley to Manchester) was opened in the summer of 1761.

In 1912 E. A. Pratt emphasized the significance of the Sankey venture. In a long section (9) he described both the chief constructional features of the canal and its economic importance and he concluded with the specific statement that:

“It is incontestable that the Sankey Brook Canal both started the Canal Era and formed the connecting link between the river improvement schemes of the preceding 100 years and the canal schemes. . .”

Pratt’s clear statement has been curiously ignored, and it is high time that it was re-examined and reiterated. The chief object of this paper is to urge that the Sankey Navigation be once again, and more widely, recognized as a canal in the modern sense of the word, earlier in construction than and at least equal in importance to the Worsley-Manchester Canal.

Mr. S. A. Harris, after his research upon Henry Berry, Liverpool’s second dock engineer,(10) was able to show that Smiles was mistaken when he claimed that Brindley and Smeaton were the only engineers in the country “of recognized eminence” in the mid-eighteenth century. Berry was not only a most important figure in the history of Liverpool dock construction; he was also surveyor and engineer of the Sankey Navigation. It is a second object of this paper to plead that Berry be given his rightful place beside Brindley and the other early engineers.

THE ECONOMIC BACKGROUND

Professor Nef has expressed the opinion that “The more we study the history of communication by water in England, the more do we realise how closely it is interwoven with the history of coal”.(11)

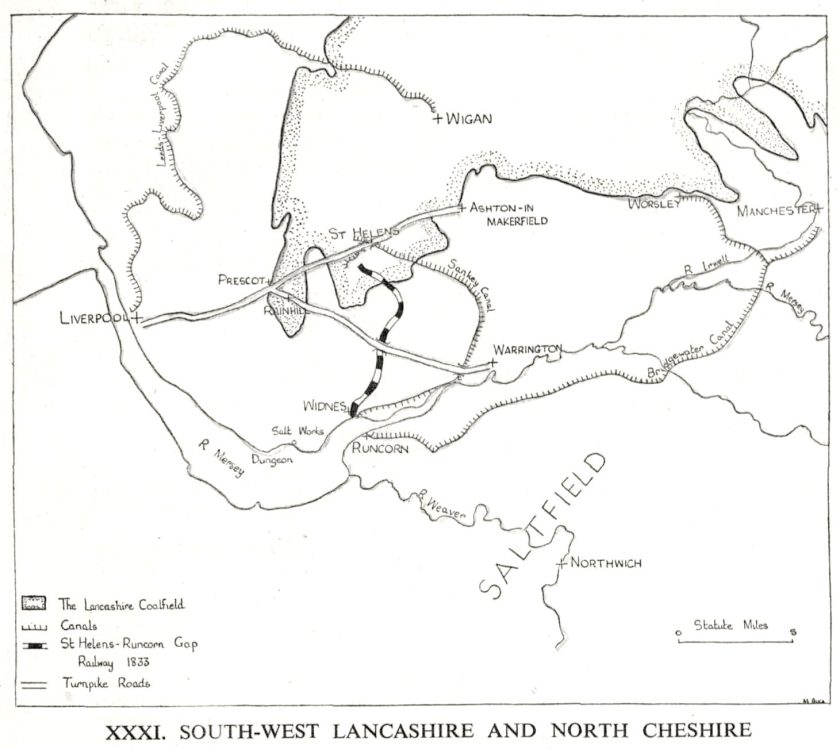

This generalisation certainly holds good for the Sankey Canal. The shortage of coal, required in increasing supply by the population of Liverpool,(12) and by the salt boilers of Cheshire,(13) Dungeon,(14) and Liverpool itself,(15) caused the consumers of coal in the first place to investigate the possibility of making the Sankey navigable.

The petitioners for the Act of 1755 claimed that “The said towns of Liverpool and Northwich have generally been supplied with coal from the coal pits and coal works at and near Prescot and Whiston in the county of Lancaster . . . [but] such coal hath of late years become scarce and difficult to be got, and, as well from the advanced price thereof at the pits, as of the rate of carriage from the same, is become very dear to the great discouragement of the trade and manufactories of the said places.” (16)

Despite the turnpiking of the road from Liverpool to Prescot(17) and later to St. Helens(18), the improvement in the road surface was not sufficient to withstand the additional wear and tear which resulted from the greater traffic in coal to Liverpool. The crescendo of protests at the acute short age of coal, “scarce and difficult to be got”, grew steadily during the first half of the eighteenth century and reached a climax early in the seventeen-fifties when both the Turn pike Trustees and the coalmine proprietors raised their charges.

In April 1753 the Trustees were empowered to extend the Turnpike from Prescot to Warrington and from St. Helens to Ashton.(19) A higher toll was imposed to meet the cost of these extensions.(20) The raising of the toll and the enforcing of Broad Wheel legislation occasioned the first local instance of turnpike rioting.(21) The price of coal was raised still farther about this time in order to pay for a new pump, installed at the Prescot Hall Mine which possessed a virtual monopoly of the Liverpool coal market.(22) The Vicar of Prescot reported on 7 April 1759 to the Provost of King’s College Cambridge(23) that

“They erected about 6 Years ago a new Engine and extended their pav’d Road to That Engine and Pits adjacent at the Expense according to their own Report of 2000 Pounds; but consider at the same Time they rais’d the Price of Coals and continued the Rise 4 or 5 years wch amply repay’d ’em at the Consumers Expence; for if they get Communibus Annis 8000 Works and Each Work rais’d from 12 Shills & 6 Pence to 15 Shs, I’ll leave You to judge who suffer’d.”(24)

“About 6 Years ago” from April 1759 would place the date of the 20% increase in the price of coal at Prescot in about April 1753, precisely the time when the Turnpike extension was permitted. The two increases in coal charges levied simultaneously by the Turnpike Trustees and the proprietors of the coal mine at Prescot turned what had been an irritating hardship into an intolerable imposition.

Clearly, a navigation communicating with the coalfield to the east of Prescot would at once serve two purposes. It would establish ready access to a rival coal-bearing district and break the monopoly enjoyed by Prescot and Whiston.

It would provide an alternative means of communication between mine and market which would not only compel the Turnpike to reduce its tolls but, more important, would also increase the amount of coal which could be transported, for the Turnpike imposed severe limitations on the movement of coal. A pack-horse could carry little and a coal cart was restricted by the state of the road; but a thirty-ton vessel on a waterway could move a greater tonnage more reliably.

There were telling reasons both economic and mechanical why the interested parties should cast their eyes upon the coal pits of the Parr area and should examine the possibility of making navigable the Sankey Brook which flowed from this more easterly section of the coalfield down to the Mersey near Warrington. It was already navigable for over a mile of its length up to Sankey Bridges.(25)

Coal-getting in Parr and neighbourhood was already on the increase.(26) Perhaps the local landowners’ and coalmine proprietors’ claim in their petition to Parliament that there existed “several great coal mines or coal works”(27), may have been a little exaggerated even by eighteenth century standards. The larger the undertakings were stated to be, the greater would be the chance that the Parliamentary committee would lend a sympathetic ear to the navigation project. Nevertheless, in the pits of the district the consumers of coal in Liverpool and elsewhere must have seen coal workings of sufficient size and promise to merit their attention.

Although the citizens of Liverpool stood to gain from the opening up of this part of the coalfield, two people were particularly interested. One was John Blackburne, junior, who owned the Liverpool saltworks and was dependent upon a cheap and plentiful supply of coal for the expansion of his business.(28)

The other was Sarah Clayton, a prominent Liverpool figure in 1754,(29) who was Lady of the Manor in Parr.(30) A waterway right up to her coal-bearing lands would increase their value very considerably. In fact, Miss Clayton was one of the first people to cash in on the navigation when it was opened. Coal from her estate in Parr was carried to Liverpool in her own flats(31) where she was also responsible for its marketing. Whether an organisation of such scope had occurred to her when the Sankey Navigation was first mooted is not known. But she was obviously an interested party from the outset, and, although as a woman her name never appears in any of the proceedings, it seems highly probable that she was pulling strings in the back ground.

The initiative was taken, however, not by Miss Clayton nor by Mr. Blackburne but by the Common Council of Liver pool, a body of considerable authority and influence at this time.(32) At a Council meeting on 5 June 1754 it was

“ordered that two able and skilful surveyors be appointed to survey the Brooke commonly called Dalham Brooke(33) which Emptys itself near Sankey Bridges in this county – such surveyors having first obtained the Licence of the principal Gentlemen or Land owners of the ground on each side of the said Brooke and that the expense thereof be paid by this Corporation.”(34)

It is unlikely that those men on the Council who voted that the survey be made at the expense of that body foresaw any departure from the customary measures to make navigable an existing waterway—to deepen the channel and cut off the bends as had, for instance, been achieved in the case of the Mersey-Irwell Navigation with which Liverpool merchants had previously been connected.(35) It was one of the “two able and skilful surveyors” who determined to extend the use of a cut so that the whole waterway north of Sankey Bridges came to be artificially constructed.

HENRY BERRY AND THE CANAL

The name of the surveyor and engineer who was responsible for the construction of the Sankey Navigation, Henry Berry, is not widely known. He is in many respects typical of the engineers and manufacturers of his day. Little is known about his life,(36) and any notes he may have made have not as yet been unearthed.

To cut a canal alongside the Sankey Brook, instead of attempting to make the Brook itself navigable, was daring because it raised the problem of water supply to a dead water navigation. But in some respects this deviation from previous practice was not original: small cuts were not un usual on river navigations(37) and locks had been employed on English waterways for at least two centuries.(38) Berry took the next logical step and engineered the first dead-water canal of any length in the country.(39) Its construction raised important new problems but was not a leap in the dark.

His successful accomplishment of the task, while he was still in his mid-thirties, ought not to prompt the cry of “genius” so much as the reflection that Berry was an experienced man who was willing to take a reasonable risk, but it required great natural ability and that essential capacity of the good engineer to make do with the materials at hand and to improvise when plans break down. Above all, the recipe for success in Berry’s case included two particular ingredients: a first class apprenticeship under the eye of an expert and, in all probability, a considerable knowledge of local conditions.

Shortly after the death of Liverpool’s first Dock Engineer, Thomas Steers,(40) in 1750, Henry Berry, styled “late clerk to him” in the Town Books, was instructed to “continue to oversee the works till further notice”.(41) By the following year Steers’s clerk was himself Dock Engineer.(42) This evidence suggests strongly that, as clerk to Steers, Berry was one of his right-hand men in whom the Corporation felt sufficient confidence despite his age—he was only thirty in 1750 – to appoint as Steers’s successor at a critical period in the history of Liverpool’s dock construction.(43) It appears almost certain that Berry received his training from Steers who, no doubt, relied greatly on an active, young lieutenant to deputise for him at a time when he himself was ageing(44) and was occupied with considerable civic responsibilities as an Aiderman.(45)

Steers possessed a fund of experience of great value to a young man who was both able and intelligent. The sug gestion has been made that he had been George Sorocold’s chief assistant in the construction of the famous Rotherhithe Dock in 1700.(46) It is certain that he was sufficiently well known in 1708 to be brought up from London to construct the first dock in Liverpool (1709-15).(47) His varied duties(48) subsequently included, after taking an active interest in the Mersey-Irwell, Weaver and Douglas navigations, the post of Advisor to the Newry Navigation Commission (1736-41).(49) Young Henry Berry was therefore able to learn all the theoretical principles and practical methods of waterway construction at first hand from one of the few experienced dock engineers of his day.

There are strong reasons for suggesting that Berry was himself brought up in Parr on the upper reaches of the Sankey Brook. In a codicil to his will he included the request:

“bury me at the Dissenters’ Chapel at St. Hellens, but not in the Chapel where my parents are buried but in the Chapel Yard, as I would not have their graves opened; lay a stone upon me, with only my name and age.” (50)

In the Will itself he left:

“£100 to the Trustees for the Dissenting Meeting at Saint Hellens, co. Lancaster, to be invested and the interest paid annually to the minister . . . to my niece Sarah Kenwright, an annuity of £30, payable half-yearly and charged to my estate in Parr, co. Lancaster, now in occupation of Peter Taylor, with power for my said niece to enter the said estate and distrain for the said annuity.”

The request to be carried twelve miles from his home in Liverpool (where there were at least four Dissenters’ Chapels at that time)(51) in order to be buried at the same chapel as his parents in St. Helens suggests strongly that the estate in Parr(52) was family property where Berry himself had been brought up. This supposition is strengthened by evidence from local poor law records and lists of window and land tax payments, in which the names of John, Peter and Henry Berry are mentioned. Any of these men could have been the engineer’s father. Particular attention is drawn to John Berry whose name appears in the surviving lists of window tax payments from 1720 but not in those for 1715 and 1716.

It might possibly be argued from these lists that John Berry married and set up house in Parr sometime between 1716 and 1720. If this was the case, Henry Berry might well have been their first child, born, as we know he was, in 1719. Moreover, John Berry of Parr, yeoman, was mentioned as a trustee of the Independent Chapel, St. Helens, in 1724 and 1728, and Henry Berry “of Parr Batchelor” in 1742. In 1753 and 1788 Henry Berry appeared as “late of Parr and now of Liverpool . . . yeoman.”(53) In 1756 he was styled “of Liverpool, Engineer”.(54) Although positive proof, such as the name of Henry Berry in the register of christenings of the Dissenters’ Chapel, St. Helens, is unobtainable (no register is extant) there is strong circumstantial evidence that Berry did, in fact, spend his childhood in Parr. If this is true, then he possessed an intimate knowledge of the district which was the key to the whole canal scheme, for it was from the St. Helens drainage area that the navigation was to secure its all-important water supply.

Such first-hand local knowledge would certainly have been a great asset when Berry came to carry out the survey of the Sankey Brook at the instruction of the Liverpool Common Council.

This he did with William Taylor(55) at a cost of £66:16:0(55) during the summer of 1754. His report must have convinced the Corporation that a waterway could be opened to the coalfield for, on 25 October, the Council resolved to lend £300(56) towards the payment of expenses in securing the necessary Act of Parliament,

“which said sume . . . shall be repaid to the Corporation by the said undertakers if the Bill Pass into Law. But in case the said Act shall not be obtained by reason of any opposition that then the said Corporation shall lose the said money”.

The following day an advertisement was despatched from Liverpool to the Manchester Press, giving notice that subscriptions for the 120 shares offered would be accepted at the Mayor’s office in the Exchange at Liverpool between 11 in the morning and 1 in the afternoon on 14 November and subsequent days. Subscribers were required to con tribute to John Ashton and John Blackburne £5 per share towards securing the Act.(57)

Four of the five Liverpool merchants whose names appear on the petition for the Act were prominent members of the Corporation. James Crosbie was Mayor, Charles Goore was Mayor in the following year, Richard Trafford was Mayor’s Bailiff in October 1755,(58) and John Ashton had been Town Bailiff in 1749. The fifth merchant whose name features in the petition was John Blackburne junior, the owner of the salt works, who with John Ashton was the leading promoter. Blackburne joined the others on the Council in July 1755.(59)

John Ashton deserves special mention at this point. He was the financer-in-chief of the Sankey project. A few days before his death in August 1759 he was able to bequeath to his son and three daughters 51 of the 120 shares which were issued. A committal at the outset on this scale was a considerable gamble for it was quite unknown how many calls would be made upon shareholders, or even if the Navigation could be successfully completed. In all, John Ashton financed the canal to the extent of nearly £9,000.(60)

He possessed such a large stake in the venture that his decision seems to have been the vital one. The successful completion of the canal, as will be seen, owed much to Ashton’s complete confidence in and ceaseless support of Henry Berry.(61) Ashton was to Berry what the Duke of Bridgewater was to Brindley. Of the two leading promoters, Blackburne had most to gain and Ashton had most to give.(62) The petition from Liverpool was, on 16 December, referred to a committee of the House of Commons(63) which heard evidence and reported favourably on 21 February 1755.

Petitions in support of the project were received by the committee from the merchants of Liverpool(64) and land owners and coalmine proprietors on the Upper Sankey(65) together with encouraging evidence from Berry and Taylor, the surveyors.(66) There were no counter petitions.(67) The Bill became law on 20 March 1755.(68)

The most significant feature of the Act is revealed in its title – “An Act for making navigable the River or Brook called Sankey Brook and the Three several Branches thereof”. There is no indication that the undertakers intended to embark upon the bold expedient of digging a canal all the ten miles from Sankey Bridges to the limits imposed by the Act. They were merely empowered to make the Sankey Brook navigable. In doing this, they were following the precedent of the Mersey-Irwell, Douglas, and Weaver navigations. There was, of course, the usual clause permitting the undertakers to “make such new cuts . . . as they shall think proper and requisite”(69) but few, if any, could have foreseen that this clause would be used to permit the entire waterway to be made a cut. Indeed, the fact that a cut is specifically mentioned as being necessary from Sankey Bridges to a point not far to the north(70) implies that the Brook itself was to be used as the main waterway and that this cut was a noteworthy exception.

It is possible that Berry and Taylor had only carried out what Brindley was to call an “ochilor servey or a ricconitoring”, a casual visit or two which left the snags to crop up after the Act had been secured and work had actually commenced on the project. In support of this view is the argument that, the Brook being already navigable as far as Sankey Bridges, it was logical to proceed further upstream, dredging and widening. On the other hand, there seem to be strong arguments in favour of the opinion, advanced in Berry’s obituary notice that:

“after an attentive survey, he [Berry] found the measure [making the Brook navigable] impracticable and, knowing that the object they had in view could be answered by a canal, he communicated his sentiments to one of the proprietors who, approving the plan, the work was commenced on 5 September 1755, but the project was carefully concealed from the other proprietors, it being apprehended that so novel an undertaking would have met with their opposition”(71)

It is clear from the map that the Sankey was only a brook, and certainly not a river of the size of the Mersey, Irwell, Weaver, or Douglas. Its course was far from straight and the stream was shallow for most of the year, particularly in its upper reaches. Even the winding mile and a quarter from Sankey Bridges to the Mersey (used as part of the original waterway for a few years after 1757) was insufficiently deep at neap tide, and this stretch had soon to be abandoned as part of the Navigation.(72) The brook also tended to flood in wet weather.(73) If, as has been suggested, Berry possessed an intimate knowledge of the district, he would have known these facts. Even if he had no knowledge, he ought, as a skilled engineer, to have been able to secure the necessary information for the £66:16:0 expended on the survey. On the whole, the evidence suggests that Berry kept his real project secret from all but the most intimate, being certain that the clause relating to cuts would enable him to carry out his plan without further recourse to Parliament. It is here that the full significance of John Ashton’s dominant holding becomes apparent. He was almost certainly the proprietor to whom the obituary notice referred, and he stood by Berry on this critical decisions.

There were certainly strong reasons for concealing the intended venture from all but the most intimate. The announcement that the project was to be bolder in its scope, involving as it did the question of water supply to a dead-water navigation, would no doubt have deterred possible investors who would have been reluctant to run the increased risk of failure. Counter-petitions might have been made in Parliament by landlords who were unwilling to allow their land to be covered with water. Point was given to this argument by the failure in Parliament in March 1754 of a bill to make a navigable channel from Salford to Leigh and Wigan,(74) which showed incidentally that a dead-water canal had occurred to someone else besides Berry at this time, and might well have been a topic of discussion among engineers. However, the failure in Parliament of the Salford- Wigan project only three months before Berry was ordered to make this survey of the brook, can hardly have passed unnoticed by him. There was everything to be said for secrecy and little for frankness until the act had been obtained and the shareholders had committed themselves.

Once digging had commenced, however, the secret could not be kept for long,(75) but the eventual manifestation of policy did not alienate the sympathies of the Corporation. In May 1756, for instance, they granted leave

“to the Proprietors of the Sankey Navigation to get a small quantity of stone in quarry hill Delf for the use of the Navigation, gratis.”(76)

Nothing whatever is known of the problems with which Berry was confronted while making his ten-mile cut (77) to St. Helens. On 7 May 1755, six weeks after Parliamentary consent had been obtained, the Liverpool Council resolved

“That liberty be given to Mr. Berry for Two Days a week to Attend the making Sankey Brooke Navigable—he providing and paying a skilful person to superintend the works of the docks in his absence— to be approved by the Council.”(78)

On 4 November 1757 an advertisement appeared in No. 27 of the Liverpool Chronicle announcing that “Sankey Brook Navigation is now open for the passage of flats to the Haydock and Par collierys”.(79)

Of the actual cutting of the canal in the intervening two and a half years, the only known evidence is its completion. Of the hundreds of navvies, masons, carpenters, carriers and others who must have been set to work, virtually without any mechanical aids, to accomplish such a huge task in the time, not a line, so far as can be ascertained, was written in the Press.(80) Although the Act named 258 persons to serve as commissioners (the quorum being seven) to settle out standing claims for damage and compensation between land owners and undertakers, none of the commissioners’ decisions are to be found among Deeds Enrolled in the Quarter Session Records as directed by the Act.(81)

A copy of the Articles of Arbitration between the land owners of Parr etc., and the proprietors of the Sankey navigation, however, survives.(82) It reveals that on 9 December 1756 Articles of Agreement were drawn up between nineteen landowners and sixteen tenants(83) and the undertakers

whereby Thomas Sixsmith of Great Sankey, yeoman, Henry Worsley of Golborn, yeoman, Richard Ackers of Rainhill, joiner, James Cross of Windle, yeoman, and John Birch of Bold, yeoman, or any three of them, were to arrange compen sation payments according to the Act of Parliament and “to keep peace And Amity between and Amongst the said Partys”. They were to meet yearly in February or at other times when necessary, seven days’ notice having been given of meeting, to..

“View and Survey the said Lands, Tenements and Hereditaments belonging to the said Landowners and in the possession of them and their said ffarmers and Tenants . . . And shall Estimate and Value the Loss and Damage that in the preceding year . . . hath been done thereto by Cutting using or Overflowing any part or parts thereof that shall be Lessened in Value by not being flooded in Winter as Usuall or by the Waters being took from Parr Mill so as to prevent its Working at any time or times or in any other Manner”.

Elaborate precautions were taken to ensure that meetings were called as prescribed and that lazy referees were replaced.

The compensation payments were made for loss of right and there were no conveyances of surface lands.(84)

Two further scraps of information relate to the canal during the dark two and a half years from the summer of 1755 to November 1757.

Owners of land in Windle:- Sir Thomas Gerard of Garswood, Thomas Moss of Farnworth (clerk), Thomas Leigh of Warrington (apothecary), Hugh Glover of Hardshaw (weaver), Peter Berry of Windle (coalminer), Ellen Harrison of Windle (widow), Elizabeth Orrel of Parr (spinster).

Owner of Land in Sutton:- Peter Bold of Bold.

Tenants:- Peter Birchall, Hannah Hindley, Peter Johnson (3 farmers, Sarah Clayton’s tenants); Hugh Gomery of Parr (yeoman), Richard Greenough of Parr (farmer), Henty Martland of Parr (farmer), John Sutton of Parr (farmer), William Johnson, Elizabeth Gore, Robt. Hoole, Thomas Speakman, John Rigby (four farmers of Parr), Wm. Marsh, Margaret Hart (two farmers of Windle), Nehemiah Johnson of Sutton (farmer), John Rigby of Parr.

The first concerns the financing of the undertaking. Of the £155 paid up on each share, £90 was taken in 1756 and 1757.(85) The total capital paid up in the first eight years of the undertaking was £18,000.(86) The second is an entry in the Minutes of the Turnpike Trustees dated June 1757 which reads:

“An application being now made . . . by the Proprietors of the Sankey Navigation, desiring their opinion as to Erecting either a stone or a Wood bridge near unto Sankey Turnpike gate; it is thought that a Wood bridge will be the most proper and be much Easier to all Passengers”.(87)

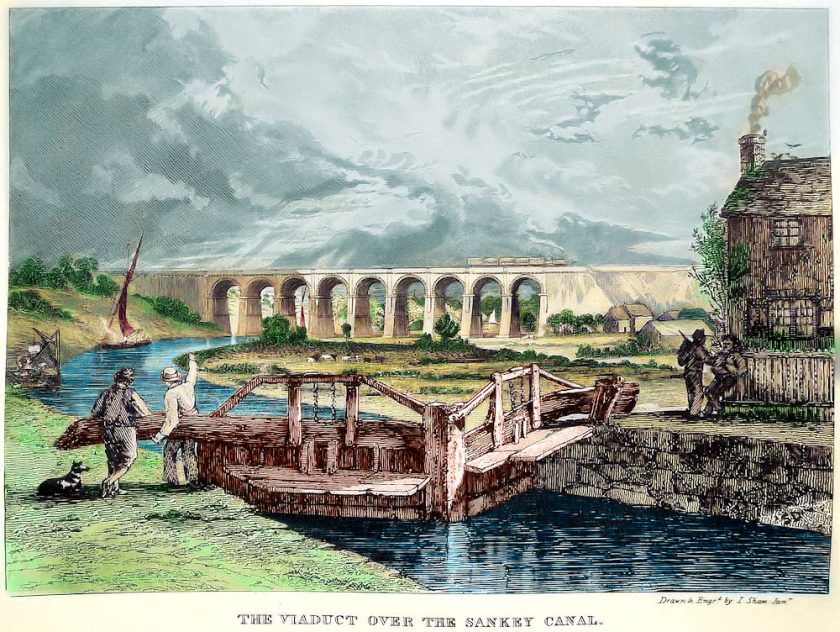

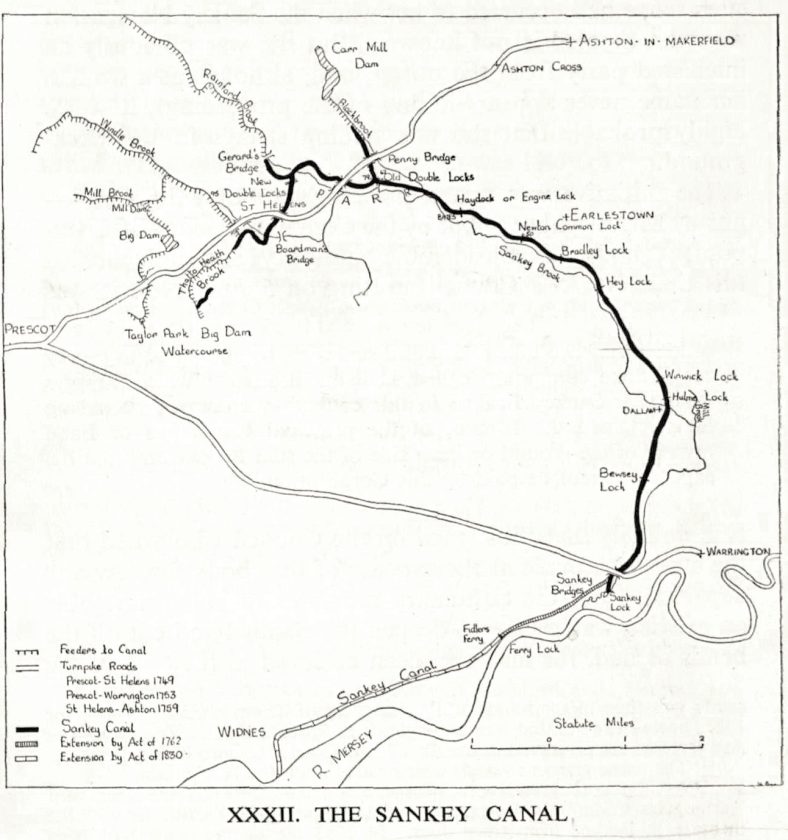

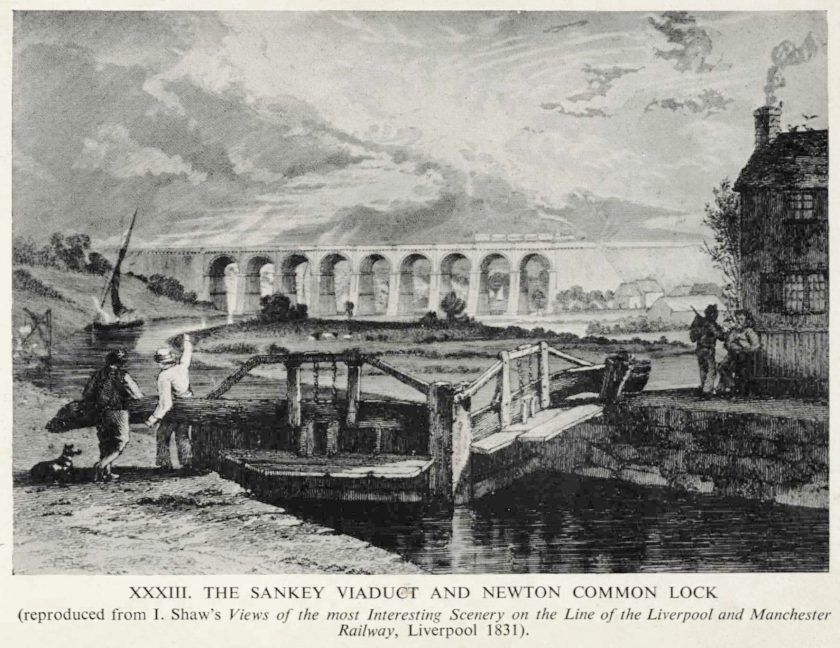

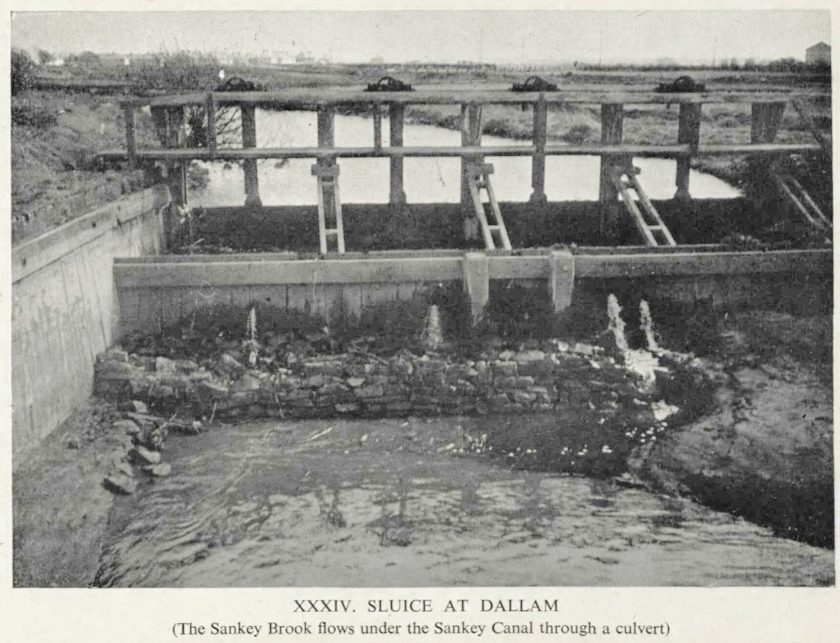

A brief glimpse at the newly-completed canal may compensate a little for the absence of information concerning Berry’s methods of meeting constructional difficulties. In particular such a glimpse reveals how the main difficulty of water supply was solved. The waters of the streams which drained into the upper reaches of the Sankey Brook—Blackbrook, Rainford Brook, Windle Brook and (later) Thatto Heath Brook—were tapped to supply the canal. The Old Double Locks at St. Helens dropped the water level in the canal by some 20 feet. The Penny Bridge and Gerard’s Bridge arms, constantly fed by the local brooks, thus served as a reservoir and provided a good head of water for maintaining the level in the canal to the south which ran at a higher level than the Sankey Brook itself, raising many problems of banking and reinforcement no doubt. In many parts of its length the side of the valley was used as one wall, and the floor and western side of the canal were built up. Occasional weirs and sluice-gates drained off any excess flood water from the canal down into the brook. The brook thus fulfilled a twofold function of water supply and flood prevention.

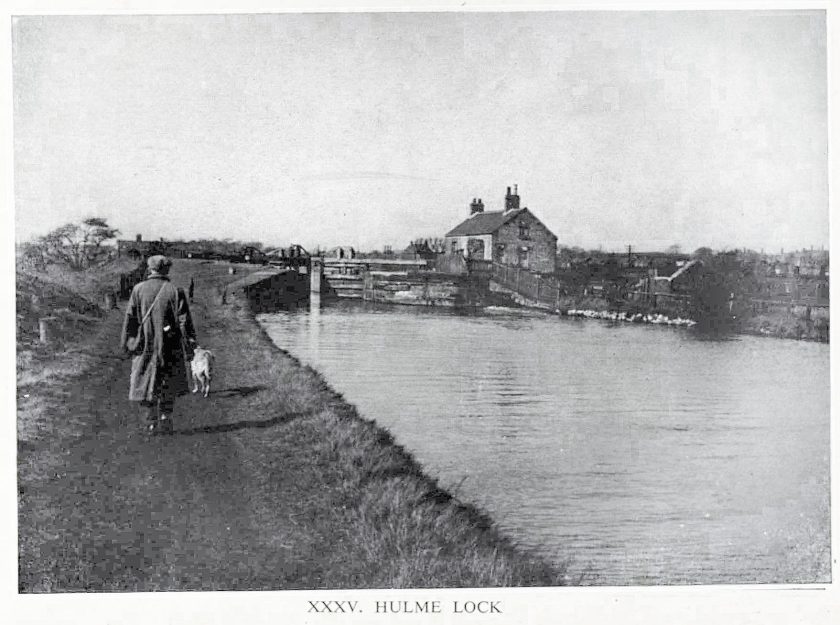

The canal originally joined the brook by the Sankey Lock, a little below Sankey Bridges, to which point the brook had previously been navigable^ From this junction, nine locks(88) carried the canal up some sixty feet to the point where it forked into two arms, the northern arm continuing towards Penny Bridge and the western arm to Gerard’s Bridge.

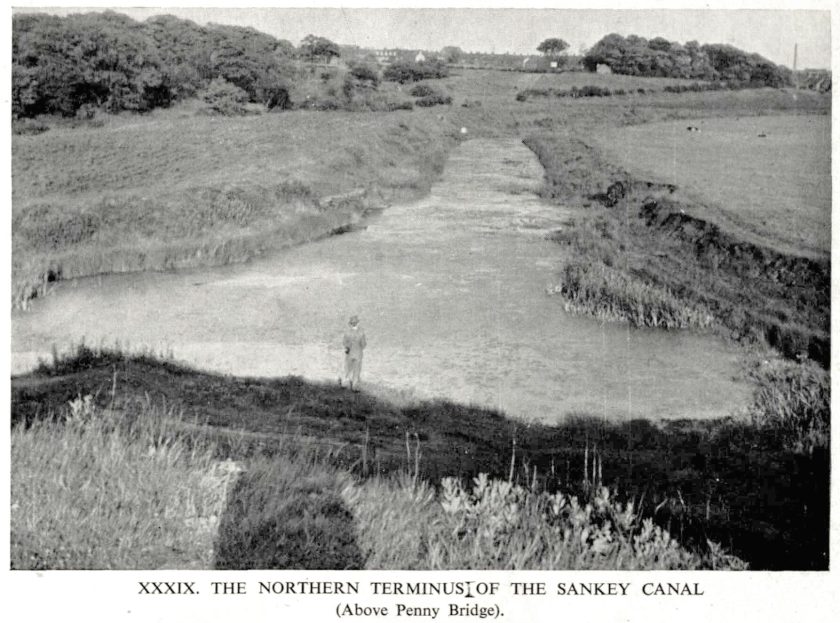

The undertakers were empowered to extend these branches up to 800 yards(89) above these bridges and were pressing on towards these northern and western limits after they had announced that the canal was open as far as Hay dock and Parr collieries in November 1757. A Plan of 1763,(90) based on a survey in 1759, shows that the canal had been completely built as far as Gerard’s Bridge by the spring of 1759. The northern arm (to Penny Bridge and beyond) was half-finished.

It was soon found that at neap tide the depth of water was insufficient below Sankey Bridges where the brook was still being navigated. Parliament was, therefore, petitioned in 1762 for a second Act which would allow the extension of the canal from a point 250 yards below Sankey Lock to Fidler’s Ferry.(91) Although this improvement in the navigation went far to solve the neap tide problem, flats continued to be neaped occasionally until, by an act of 1830, the canal was further extended to Widnes.(92)

A noteworthy feature of the canal was the employment of swing bridges, instead of hump-back bridges, which were later to become customary elsewhere. The rotating of the bridge parallel to the bank permitted flats to sail up the canal under favourable conditions. If the wind was too low or the flat too heavily laden, horses were employed. There would seem to be little foundation for the assertion that the flats were hauled by men, although it is possible that if the flat were becalmed in mid-canal the crew might take to the towpath as a last and desperate resort.(93)

Eager adventurers, quick to take advantage of the possibilities of the new waterway, were soon erecting warehouses and wharves on the banks of the canal. One of these was Peter Orrett, who forsook a steady job as surveyor of the Prescot to Warrington Turnpike(94) for a gamble by the canal. In January 1758 the following proud proclamation appeared in the Liverpool Press:

“Sugarmolds, drips, stone bottles etc. Black mugs, mottled mugs and plate ring, will be made this spring on Sankey Navigation at Bewsay Kay, now erecting by Peter Orrett and Co. and sold on the lowest Terms. All persons that have Business to be transacted on or near the Navigation, at Warrington, either to buy or sell; the same will be punctually performed, on small Brokerage, either privately or by public Auctioneering. Shares of the Navigation, Annuities or Estates will be bought and sold or persons that be minded to put out money at a large interest, for life, may be treated with on commission- And all gentlemen who please to favour them with their commands may depend on being punctually served by Their humble servants Peter Orrett and Co.

“N.B. The said Peter Orrett will give constant attendance and have a proper Assistant; and will have a warehouse to take in goods for the neighbouring places, and a sloop, constantly plying on Freight etc. and will deliver at any Kay. All letters will be punctually answered and may be directed for Peter Orrett and Co. at Sankey Turnpike Gate; the Nagg’s Head at Warrington; or at his House at Bewsey Kay Mug Works. Salt, coal, kannel, limestones, sopers waste, slate and lime bought and sold.”(95)

A year later a sad confession slipped into the advertisement columns of the same Liverpool paper:

“Whereas Mr. Peter Orrett of Prescott, in the county of Lancaster, has through misfortunes become unable to pay all his Creditors . . . judgement was thereupon forthwith entered up against him, and Execution taken out thereon, and his Personal Estate sold and disposed of . . . It appears . . . that the Estate and Effects of the said Mr. Orrett were at that time of the value of near £600 and that the Debts due from him are about £800”.(96)

Peter Orrett was too adventurous and failed. Others were more wary and succeeded.

THE ECONOMIC RESULTS OF THE NAVIGATION

Despite the fact that the upper branches of the canal were unfinished and that the use of the brook itself on the last mile and a quarter involved severe tidal difficulties, coal was being transported via the canal to Liverpool from November 1757.(97) The Act permitted the Undertakers to charge 10d. a ton on coal, stone, timber and merchandise which passed through the canal.(98) They were able to pay the first dividend on 3 April 1761, “the said navigation being brought to some degree of perfection”(99)

As a result of the unhappy experiences of the Liverpool townspeople in the past with short weights of coal at the pit, the Act of 1755 fixed a standard coal measure in order to avoid “Frauds and Abuses to the Buyers and Consumers”, A standard bushel of prescribed size(100) was to be kept, sealed, in the Exchange at Liverpool along with the other standard measures of the Corporation.(101) All merchants in Liverpool who dealt in coal which was brought via the Sankey Canal were to use this standard as were the coal owners on the Upper Sankey, whose measures were to be taken to the Exchange at Liverpool to be sealed on pain of a £50 fine.

A few months after the opening of the canal, the price of coal in Liverpool stood at 7s. a ton “to such vessels at Liverpool as the Flats can lay along the side to discharge into” and 7s. 6d. delivered to householders in the town itself.(102) The previous charges are not known so it is impossible to make any comparison with the prices which had obtained before 1757. Even if a price list of Prescot coals at Liverpool were available, any accurate comparison would be difficult on account of the lack of uniformity in weights used before the introduction of the sealed bushel. However, it is known that coal was loaded on the flats in Parr for 4s. 2d. a ton.(103) Allowing 10d. for canal dues, the cost of carrying a ton of coal amounted to 2s. to vessels in the Mersey and 2s. 6d. to the householder’s coal-hole.

These transport charges on the canal must have compared most favourably with the costs for coal carted along the turnpike road.(104)

Moreover, greater loads were carried on the canal, and seasonal shortages did not occur.(105) The original flats were of about 34 or 35 tons,(106) owned by private people like Sarah Clayton.(107) According to a Parliamentary Report of 1771, 45,568 tons were carried down the canal to Liverpool and 44,152 tons to Warrington, Northwich and elsewhere.(108) The constant complaints from Liverpool about irregular and inadequate coal supplies, which had been a feature of the previous thirty years, ceased at last.

In 1773 the extension of the Duke of Bridgewater’s canal was opened down to the Mersey at Runcorn and a small dock was built for Bridgewater flats at Liverpool.(109) The following year the Leeds and Liverpool canal carried flats full of coal from the Wigan field into Liverpool itself. This waterway rapidly replaced the Sankey Navigation as the chief source of the domestic coal supply of the port. A writer in 1797 relates that the Leeds and Liverpool Navigation brought “at a moderate rate, not only the best but the greatest quantity of coals consumed by the inhabitants.

The canal terminates at the northern quarter of the town whereby the expense of carriage of this useful article to the houses becomes small”.(110) In face of this competition from Wigan the collieries on the Upper Sankey concentrated upon supplying industrial and export markets in Liverpool. When, in October 1773, ready access was gained from the collieries at Thatto Heath to the Sankey Navigation at Ravenhead, it was particularly noted that “smith’s coal, a valuable article of exportation from Liverpool to America, was obtained thereby”.(111)

Forty years later, Matthew Gregson remarked that:

“The coals that are at present conveyed by this canal [Sankey] are chiefly consumed by the different salt works and but few come down to Liverpool except what are for Breweries, Copperas works etc.”(112)

It would appear, therefore, that Liverpool secured greatest returns from the Sankey Navigation during the fifteen years which immediately succeeded its opening. During these critical years in the port’s growth, the coal which was carried down the Sankey warmed the town of Liverpool, and even allowed a small margin for export. It tided over a difficult period until alternative sources of coal supply could be obtained. The initiative of the Common Council on behalf of the citizens had been well timed and all their efforts well placed. Considerable hardship, which might have tended to arrest the development of the port, was avoided by the opening of the Sankey Navigation in 1757.

In 1773, when Liverpool’s urgent need had been met, the St. Helens area itself began to profit industrially from the canal. It was in that year that an Act was passed, permitting a group of men, who called themselves the British Cast Plate Glass Manufacturers, to establish at St. Helens the first large plate glass works in the kingdom. By 1773 Liverpool’s great advantage from the Navigation was ending; that of St. Helens was about to begin.

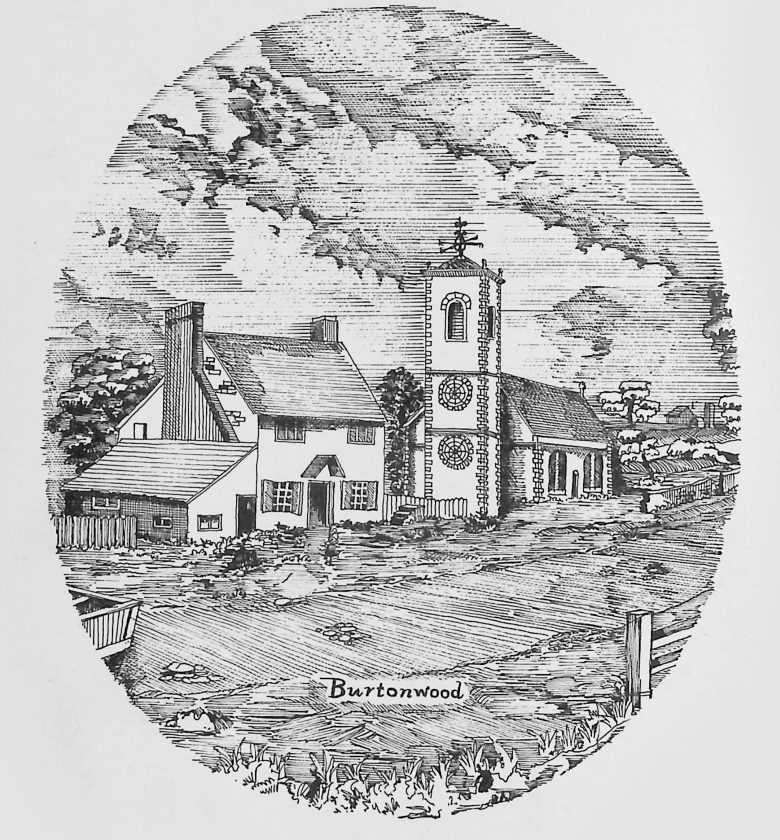

Before the middle of the eighteenth century there is very little evidence of industrial activity in or about the district which later grew into the town of St. Helens. A chapel-of-ease(113), a Dissenters’ Chapel, a Quaker Meeting House and an inn,(114) situated at the point where the Warrington-to Ormskirk and the Ashton-to-Prescot roads ran together, were surrounded by a few houses and cottages dotted about the neighbouring countryside. Most of the local population were farmers together with a few craftsmen engaged in the old established local pottery making. Here and there were isolated instances of coal-getting, which had been taking place in the district for two centuries.(115) There was a small though growing local market for this coal in the glass houses of the neighbourhood of which there is information early in the eighteenth century.(116) It is worthy of note that glass, for which the town later became famed, was being produced locally in a small way (taking advantage of the coal and sand of that part of Lancashire) before the coming of the large firm, the British Cast Plate Glass Manufacturers.

It was the absence of good communications from the area that arrested the development of the small-scale glass industry and of coal mining.

The expansion of Sarah Clayton’s coal pits in Parr is a good indication of the increase in coal-getting in the district which followed the opening of the canal.

She was able to announce in January 1758 that two delfs were already open “and a Quantity of each Delf got ready for Sale”.(117)

In 1760 a new manager for the pits was appointed at a salary of £50 a year plus a quarter of the profits together with a house and all reasonable expenses. Three years later, under a new agreement, this was altered to £60 or a tenth of the profits whichever was the greater. In 1765 he was allowed an assistant whom he was able to pay out of his own salary.

At the end of 1768 the undertaking had expanded to the point where the assistant was entrusted with “the business of managing the colliery in the field” while the original manager confined himself to book-keeping to be “managed and conducted in the most careful and judicious manner that could be contrived” with an inspection “once a quarter at farthest.”

In 1773, however, it was found that he had “kept his books in a most irregular manner and therein made sundry charges for money paid by him which he did not pay and for which he hath no receipts”.(118) Five years later this “very valuable coal mine” had to be sold up,

“with all the horses, waggons and other carriages, railed roads, ways, windlasses, materials and utensils thereunto belonging, particularly a remarkably good fire engine lately erected and in thorough repair, so as to require little expense during the time the coals may reason ably be expected to take in getting: The quantity about thirty thousand works”.(119)

Sarah Clayton’s loss is the historians’ gain. The gradual elevation of the position of manager of these pits gives a clear indication of the expansion of the undertaking, con firmed by its extent at the time of sale. Although Clayton, Case and Company failed, many similar mines in the district continued to thrive and to be compensated for the loss of shipments to Liverpool for domestic purposes by the increasing demands of the industries at that port, of export buyers, and, most significant of all, of new local industry.

A plentiful supply of coal, near at hand, cheap to buy, combined with good communication by water to Liverpool, Manchester and elsewhere, tempted would-be manufacturers to explore the land, undeveloped and inexpensive as it was, on the upper reaches of the Sankey. At first, a deterrent was the absence of accommodation for the work people and, for a time, the new factories had to provide the necessary living accommodation near to the works.(120)

Later, the private builder and retail shopkeeper sought to cash in on the economic possibilities of the district,(121) and the town was born. By the time of the first detailed map of South Lancashire(122) many buildings flanked the stretch of road where the Ashton-Prescot and Warrington-Ormskirk highways ran together. Such were the origins from which the new town was to grow. They were the direct result of the cutting of the canal which had put the district into closer economic touch with the rest of the country and had attracted new industry.

Few would claim that the Sankey Navigation possessed at any point the magnificence of an aqueduct such as Brindley constructed at Barton or the ingenuity of a subterranean tunnel such as that at Worsley; yet it is worth while to emphasize the Sankey’s priority in construction and (at least) equality in economic importance.

The Sankey Navigation may be called a utility canal. It was built, without any claim to magnificence, in order to carry coal and was swiftly completed under the expert eye of Henry Berry. The cut from Sankey Bridges to Parr, which was open to flats in November 1757, has stood the test of the years. It marked the beginning of the modern English canal system, for Berry had struck away from the previous practice of river improvement, and although his new navigation kept close to the course of the Sankey Brook its successful completion proved beyond any doubt to Englishmen that a dead-water canal of considerable length could be built quite apart from an existing river provided that adequate water supplies could be maintained throughout the year and channels built to drain off excess flood water.

As Smiles has brought out, one of Brindley’s main characteristics was his enquiring mind. It seems to the present writer highly improbable that James Brindley embarked upon the Worsley-to-Manchester Canal without having first acquainted himself with the chief features of Berry’s master piece which was already in operation only twelve miles away.(123) In two respects the Sankey and Bridgewater Canals were identical in construction, and in a third they were similar. Both employed clay-puddle in order to prevent the water from seeping away.(124) Both were partly constructed “on sidelong ground . . . cut down on the upper side and embanked up on the other by means of the excavated earth”.(125) In both, brook and canal were prevented from mixing.(126) It is unfortunately impossible to discover to what extent Brindley copied between 1759-61 these three fundamentals which Berry had already applied with such success between 1755-7. Given Berry’s experience as a dock engineer and Brindley’s known capacity to memorize detail and (in fairness, it must be added) to improve this detail in his own execution of it,(127) Brindley’s great success as a canal engineer is more easily understood. Without the ad vantage of Berry’s experience (particularly at the Liverpool Docks under Steers), the jump from mill engineer to canal builder may seem too great, perhaps, even for a Brindley.

Economic as well as chronological importance may also be claimed for the Sankey Navigation. The Sankey flats carried coals to Liverpool at a critical stage in the port’s development and, as Professor Mantoux has noticed, “The growth of Lancashire, of all English counties the one most deserving to be called the cradle of the factory system, depended first of all on Liverpool and on her trade”.(128) When supplies of domestic coal were obtained more easily from other sources, the industrial and export markets were kept satisfied at Liverpool. Of the many other districts which profited when water communication was established with the St. Helens coalfield, the greatest beneficiaries were the salt boilers of Cheshire whose shipments of white salt down the Weaver increased rapidly. Moreover, the siting of glass and copper smelting works in St. Helens, a direct result of the cutting of the Sankey Canal, was of considerable local importance for it laid the foundation of an urban area which became a centre for industry of a highly distinctive character—glass and chemicals—in the course of the nineteenth century.

THE CANAL AFTER 1830

The evidence given at the Enquiry, held in London in November 1930, which led to the closing of the canal north of Newton Common Lock, provides an outline of the later history of the Canal.(129)

The St. Helens and Runcorn Gap Railway, opened in 1833, proved very profitable, and in 1845 (8 & 9 Victoria cap. 117) the canal and railway were united. In 1864 (by 27 & 28 Victoria cap. 296) both passed to the London and North Western Railway Company.

After 1900 the northern part of the canal up to St. Helens was little used. A report, dated 8 May 1914, stated:

“For several years there has been a considerable decrease in the number of canal boats coming into the borough of St. Helens; it is reported that not more than 20 boats carrying cargo have passed through the New Double Locks at Pocket Nook to any of the works on the canal during the last fourteen years”.

Seven flats passed through Newton Common Lock in 1919, the last to navigate the northern waters up to St. Helens.

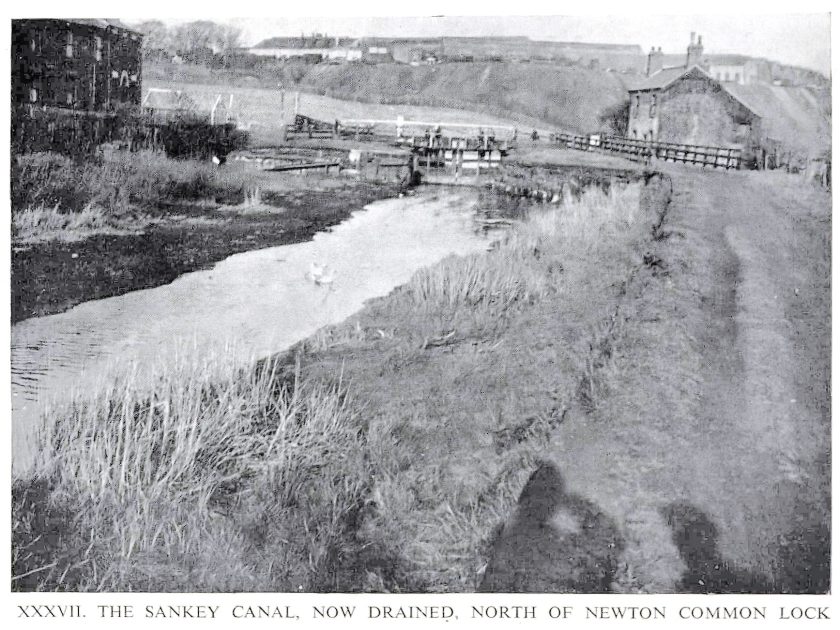

The County Borough of St. Helens was anxious to widen the roads passing over the three arms of the canal and, particularly, to remove the narrow swing bridges which formed bottle-necks on the main thoroughfares’. Two stretches of the canal on the Ravenhead arm had already been closed in 1898 and 1920. The Railway Company, anxious to avoid an annual loss of £1,000, joined St. Helens Corporation in appealing for an Inquiry, which was held in 1930 and resulted in an Order, dated 21 May 1931, by which the canal was closed north of Newton Common Lock, more than five miles in length.

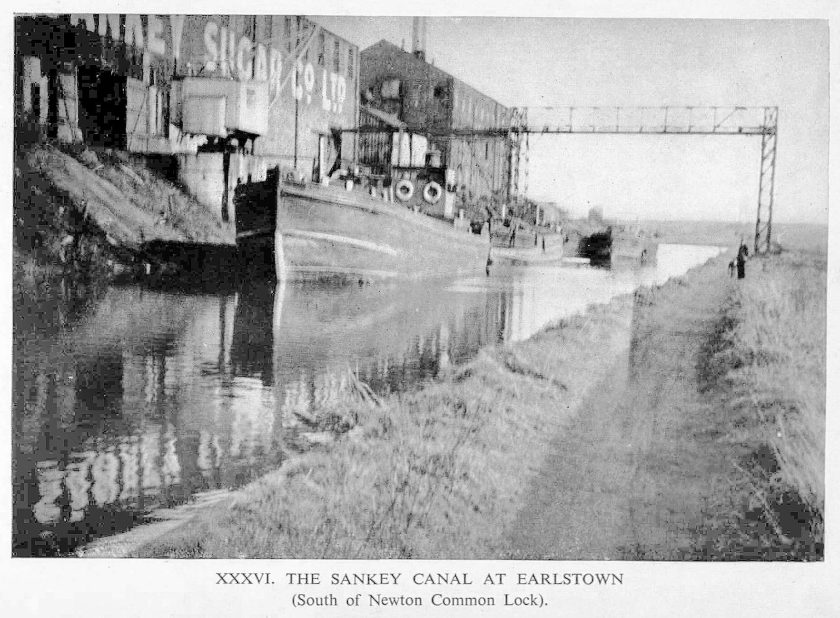

Although motor barges continue to navigate the canal up to the wharf of the Sankey Sugar Company, to the north of this refinery the banks and bed are overgrown (claimed in places by eager allotment holders) and the trickle of water, which still flows to feed the navigable part to the south, is graced here and there by an occasional duck, as seen in Plate XXXVII.

The maps on included here were drawn by Miss Muriel Buck, B.Sc., to whom the writer wishes to express particular thanks.

References..

1. Arthur Young, A Six Months’ Tour Through the North o f England (London, 2nd edn., 1821), Vol. Ill, p. 187.

2. Smiles, Lives of the Engineers (London 1861), Vol. I, pp. 307-476.

3. A few days before his visit to Manchester, Young had gone from Warrington to Liverpool on which journey he must have crossed the Sankey Navigation. Although he devoted some space to a description of manufactures at Warrington (op. cit., Vol. Ill, p. i65) and of farming nearby (ibid., pp. 165-6), he made no mention of this canal.

4. “P. Mantoux, The Industrial Revolution in the Eighteenth Century (London, 1927), p. 127.

5. G. M. Trevelyan, English Social History (London 1944), p. 385.

6. T. S. Ashton, The Industrial Revolution, 1760-1830 (London 1948). Brief mention is made of the ‘ canalization of the little Sankey Brook ’ at the close of a paragraph on river improvement schemes (p. 46). The Duke of Bridgewater, however, is stated to be the one who created the new form of transport (p. 17).

7. For instance, Professor G. D. H. Cole (Persons and Periods, London 1938, p. 116) called the Sankey Navigation “an embryonic canal”. Other references may be found in Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol. LXIII (1792), No. 4, p. 909; E. Baines, Lancashire Directory, (Liverpool 1825), Vol. II, pp. 468-9; J. Priestley, Historical Account o f the Navigable Rivers, Canals and Railways Throughout Great Britain (London 1831), pp. 591-2; J. Phillips, General History o f Inland Navigation (London 1803), p. 283; R. Brooke, Liverpool During the Last Quarter o f the Eighteenth Century (Liverpool 1853), pp. 105-6; J. Touzeau, Rise and Progress o f Liverpool 1551-1835 (Liverpool 1910), Vol. I, p. 498; J. Ramsay Muir, History o f Liverpool (Liverpool, 2nd. edn. 1907), pp. 178-9; A. P. Wadsworth in A. P. Wadsworth and J. de L. Mann, Cotton Trade and Industrial Lancashire (Manchester 1931), p. 221.

8. W. T. Jackman, Transportation in Modern England, (Cambridge 1916), Vol. I, pp. 355-6.

9. E. A. Pratt, A History of Inland Transport and Communication in England (London 1912), pp. 165-7.

10. S. A. Harris, “Henry Berry (1720-1812): Liverpool’s Second Dock Engineer”, TRANSACTIONS, Vols. 89 (1937) and 90 (1938).

11. J. U. Nef, Rise o f the British Coal Industry, 1932, Vol. II, p. 111.

12. Since Defoe had paid his visits to the port half a century earlier and proclaimed that it was “one of the wonders of Britain”, there are indications that the size of Liverpool had been quadrupled. Estimates of the population are unreliable but a rough measure of the growth of the town may be found in the burial figures (av. 1700-9, 163; av, 1745-54, 778, quoted in A General Descriptive History o f the Antient and Present State o f the Town o f Liverpool, Liverpool, 2nd edn., 1797, p. 60), income of the Corporation (in 1760 almost quadruple that of 1720), dock dues (1724, £810; 1760, £2,383), and clearage of shipping (seven years ending 1716 average a little over 18,000 tons; seven years ending 1756 average 62,000 tons). The last three sets of figures are from W. T. Jackman, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 357-8.

13. It is possible to reach a rough estimate for the salt boilers of Cheshire despite the absence of any accurate figures for coal consumed. Figures for white salt shipped down the Weaver (A. F. Calvert, Salt in Cheshire, London, 1915, p. 284) show an increase from 5,202 tons in 1732, when the Weaver Navigation was opened, to 17,606 tons in 1750. It was estimated in 1773 that 15 cwts. of coal were, on average, required to produce 20 cwts. of white salt (A. F. Calvert, op. cit., p. 942). The increase in demand by the Cheshire salt boilers was therefore from about 4,000 tons to about 12,000 tons between 1732 and 1750. That this estimate may err, if anything, on the low side, is suggested by the knowledge that in 1796 100,000 tons of white salt were produced while coal consumed between 1796 and 1806 averaged almost 90,000 tons (H. Holland, The Production o f Salt Brine, c. 1806, quoted by Calvert, op.cit., p. 138). Even if consumption of coal in the first year of this decade was only 80,000 tons, this would exceed the 3:4 coal-to-salt ratio on which the previous estimate has been made.

14. More than 15,000 tons of rock salt was shipped down the Weaver in 1750 (A. F. Calvert, op. cit., p. 284). Much of this would be dissolved and evaporated in order to produce higher grade salt at Dungeon and at John Blackburne’s works in Liverpool. In 1746 the Dungeon works, equipped with four pans, was said to be “mostly new and all in good repair” with a yearly rental of £50 (Adams Weekly Courant, 9 December 1746, quoted in A. C. Wardle, “Some Glimpses of Liverpool During the First Half of the Eighteenth Century”, TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 97 (1946). For the location of Dungeon, see map on p. 125 below.

15. John Blackburne’s saltworks were in the neighbourhood of Liverpool’s second dock, opened in 1753; hence, presumably, its name—the Salthouse Dock. J. Stonehouse (“Salt and its Manufacture in Cheshire”, TRANSAC TIONS, Vol. 5, p. 116), claims that Liverpool was famous for its salt in 1703.

16. The Journals of the House of Commons, Vol. XXVII, 16 December 1754.

17. In 1726 the Liverpool Common Council decided upon the Turnpike because the road to Prescot “hath been almost unpassable and . . . the Inhabitants of this Town have suffer’d much for want of getting their Coales home Dureing the Summer season thro’ the Great Rains that have happen’d in these parts”, quoted by F. A. Bailey, in “The Minutes of the Trustees of the Turn pike Roads from Liverpool to Prescot, St. Helens, Warrington and Ashton in Makerfield, 1726-89”. TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 88, (1937), p. 160. This paper which extends into TRANSACTIONS Vol. 89, is based on the Minute Books which were discovered during the 193O’s in Prescot, and gives a full account of the Turnpike during the period in question.

18. In 1749 John Yates, the Surveyor, was empowered to expend not more than £200 in the improvement of the road between Prescot and St. Helens (F. A. Bailey in TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 88, pp. 196-7). Powers for this extension had been granted by an Act of 1746 which, according to the petitioners, would open “a Way to several Ranks of Coal-Pits, whereby all the Country adjacent and particularly the Inhabitants of the Town of Liverpool (now become very numerous) and also the Shipping of the said Port, may be commodiously served both in Winter and Summer with Coals” (quoted by F. A. Bailey, in TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 88, p. 191).

19. In April 1753 the Trustees were permitted to extend the Turnpike from St. Helens to Ashton through the coal-bearing region of Parr which the canal was soon itself to serve. But, apart from erecting a toll gate at Ashton Cross in December 1753, few repairs were made to this stretch of the road until after the canal had been opened. Its competition made improvement of the road surface imperative (F. A. Bailey in TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 89, pp. 46-7; Liverpool Chronicle, 5 January 1759.)

20. F. A. Bailey in TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 89, p. 35. The reimposition of the toll on back-carriage, discontinued in 1746, was to meet additional costs incurred in connexion with the 1753 Act. As soon as the Sankey project was definitely afoot, the Trustees made a bid to regain favour by reducing the tolls for coal—in September 1754 they were cut to half the price authorized by the Act (ibid., p. 36). But it was too late.

21. “Ibid ., p. 35.”

22. J. U. Nef., (op. cit., Vol. I, p. 359) estimated that carriage of ten miles would double or treble the cost of coal. In an attempt to counter the oppo sition of the Prescot and Whiston coal owners to the proposed extension of 1746, John Eyes, the surveyor, told a committee of the Commons that the opening of the road to St. Helens was not detrimental to Prescot because people would naturally go to Prescot, three miles nearer, if more easily and cheaply supplied (The Journals o f the House of Commons, Vol. XXV, p. 80, quoted by F. A. Bailey, in TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 89, p. 193). The Turnpike levied 1 /- a load on coal (F. A. Bailey in TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 89, p. 36). There is further evidence of monopolistic practice in a Liverpool Common Council reference to “the measure [of coal] being greatly lessened.” The inclusion of clauses in the Act of 1755 to establish standard measures both at the pits and in Liverpool was the consumers’ reply to these inadequate weights. (See below p. 146.)

23. Holders of the Manor of Prescot.

24. The writer is grateful to Mr. F. A. Bailey for his transcript of this letter from the correspondence at King’s College, Cambridge.

25. J. Aikin, Description o f the Country From Twenty to Thirty Miles Round Manchester (London 1795), pp. 110-111; T. Pennant, A Tour from Downing to Alston Moor (London 1801), p. 17. The tour was made in 1 Tri.

26. J. U. Nef (op. cit., Vol. I, p. 164) estimated that in 1700 between 25,000 and 50,000 tons was produced from that part of the coalfield which includes St. Helens, Prescot, Whiston and Sutton. It would seem almost certain that the greater part of this output came from the three districts which lay on the perimeter of the coalfield—Prescot, Whiston and Sutton—rather than from the Parr-St. Helens district which was hampered by transport expenses. The information that a pit in Sutton was in 1711 the source of 5,000 tons of coal (op. cit., Vol. I, p. 62) would seem to support this contention.

27.The Journals o f the House o f Commons, Vol. XXVII, 7 February 1755.

28. The Turnpike Trustees seemed most anxious to appease John Blackburne in his opposition to the increased tolls of 1753, a sure sign that he was an important road user. In February 1754 preferential treatment (a toll of 9d per work of coals, i.e. about three tons) was given to John Blackburne and to the Mayor, James Crosbie, on condition that their carts possessed broad wheels (F. A. Bailey in TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 89, p. 35.)

29. Miss Clayton is mentioned as one of the townspeople who stood part of the expense of public breakfasts in celebration of the opening of the New Exchange in September 1754 (History o f Liverpool from the Earliest Authenticated Period Down to the Present Time, Liverpool 1810, p. 117). She is mentioned by Baines (quoted by S. Smiles, op. cit., p. 288 note) as having possessed the only gentleman’s carriage in Liverpool in 1750. Her father had been M.P. for the Borough. See also S. A. Harris, above pp. 55-72, for further details.

30. Indenture dated 7 October 1756 in the Town Hall, St. Helens. The Parr Constables’ and Overseers’ Accounts (in the Central Library, St. Helens) include the following entry: “Parr: the Accts. o f Jonah Lyon who served the Office of Constable and Overseer of the Poor for the Estate of Mrs. Claytons called Bartons in ye year 1750-1”.

Bartons has not yet been identified. The Clayton family was certainly associated also with Parr Hall. William Clayton (Sarah’s father) in his will of 12 February 1713 bequeathed: “messuages and lands [not specified] in Parr, Rainford, and Liverpool, and pews in the Old Church and the New Church Liverpool, and in St. Ellins Chapel, Windle, co. Lancaster, to my second son William (my first being dead without issue) . . . [and] . . . household goods in Parr Hall, except silver plate . . . with a desire that they be not moved”.

The will of William Clayton, his son, dated 13 April 1723, however, makes no reference to properties at Parr. The will of Elizabeth Clayton (13 May 1740) widow of William included: “A cottage called Platts house or cottage in Parr is bequeathed to the same uses as the capital messuage called Parr-hall . . . messuages in Parr and Liverpool released from the payment of an annuity of £100 payable during the life of Samuell Byrom, esq.”

The above three wills are preserved in the Lancashire Record Office, Preston. They, and others mentioned below, belong to the Chester Probate Registry. Sarah Clayton’s sister, Margaret, married Thomas Case of Red Hazels, Huyton, and it was their son, Thomas, who joined Sarah in the coal firm. When Clayton Case and Co, went bankrupt in 1778 it was Thomas Case who sold Parr Hall (Gore’s General Advertiser, 19 June 1778), and the earliest surviving Land Tax Assessments of Parr, 1781, show that Parr Hall estate was then in the hands of the assignees of Thomas Case. Those for 1785, however, state that Sarah Clayton’s assignees held it. The Land Tax Assessments are preserved in the Lancashire County Record Office, Preston.

31. The name given to vessels which sailed upon the Navigation.

32. As the port grew more prosperous, particularly on the successful “triangular trade”, the Corporation of Liverpool became wealthier with the increase in income from town dues. In 1753 the second dock had been opened. The New Exchange was almost completed in June 1754 and was opened with considerable ceremony in the following September. It is impossible to read the distinctive hand of Francis Gildart, the Town Clerk during the period, without being impressed by the sense of authority and power which the Common Council possessed. See the section on the Mayor, Bailiffs and Burgesses of the Borough of Liverpool in S. & B. Webb, English Local Government (London 1908), Vol. Ill, pp. 481-491.

33. The Sankey Brook is called Dallam Brook as it passes through Dallam, north of Sankey Bridges (Map Directory o f South Lancashire, ed. J. Bain, London 1934, p. 162).

34. Town Books, 5 June 1754 (in the Town Clerk’s Office, Liverpool).

35. For mention of earlier cuts, see W. T. Jackman, op. cit.. Vol. I, p. 355. Note also that “The leading merchants of Liverpool were at the head simultaneously of three navigation projects—the Weaver, Douglas and Mersey and Irwell” (A. P. Wadsworth and J. de L. Mann, op. cit., p. 214).

36. The known details have been collected by Mr. S. A. Harris in his paper, “Henry Berry (1720-1812): Liverpool’s Second Dock Engineer”, TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 89 (1937). J. Hughes, Liverpool Banks and Bankers, (Liverpool 1906), p. 5, note 2, was probably the first to draw attention to Berry’s importance.

37. W. T. Jackman, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 355.

38. Cf. the lock on the Exeter waterway, 1563-7 (ibid., p. 165); the burning of lock gates on the River Lea in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (ibid., p. 168); a lock constructed on the Douglas Navigation by Steers (Wadsworth and Mann, op. cit., p. 215). The pound lock originated in Italy in the early fifteenth century (T. S. Willan, River Navigation in England, 1600-1750 (Oxford 1938), pp. 100-1).

39. For information about the cut from Exeter to the sea, accomplished with some degree of success in 1563-7, see W. T. Jackman, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 165. The distance of this waterway was so short that the double transfer of goods prevented any real competition with the road.

40. For Steers, see H. Peet, “Thomas Steers, The Engineer of Liverpool’s First Dock, a Memoir”, TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 82 (1930).

41. Town Books, 7 November 1750, quoted by S. A. Harris, op. cit., p. 93.

42. Town Books, 3 July 1751: “Mr. Henry Berry, Engineer to the Docks, admitted free gratis” (quoted by S. A. Harris, TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 90, p. 197).

43. The Salthouse Dock was being built; it was completed in 1753.

44. H. Peet (op. cit., p. 188) believes Steers may have been 39 when he came to Liverpool in 1709. This would make him 80 at his death in 1750.

45. He had been Mayor in 1739.

46. H. Peet, op. cit., p. 170.

47. See the resolution of the Common Council quoted by Peet (ibid).

48. e.g. he was Dock Master in 1717; he built the dry dock in the same year; he was charged with the buoying of the Mersey Channel in 1736.

49. H. Peet, op. cit., pp. 183-4.

50. The 2nd Codicil is dated 4 June 1808. The will (in the Lancashire Record Office) is dated 13 July 1807. Berry died on 31 July 1812, leaving a fortune of a little less than £12,500. He was buried as he wished, though the stone was not as plain as he had requested. No registers survive at the Congregational Church to check his birth (perhaps they were lost when the old chapel was pulled down and rebuilt in 1826) and his name does not appear in the parish records.

51. Paradise Street, Benn’s Gardens, Mathew Street and Renshaw Street (Gore’s Directory, 1803, p. 182).

52. A map (thought to be dated about 1830), in the Borough Engineer’s Department, St. Helens, shows land marked Henry Berry in what is now called Fleet Lane, Parr.

52. Trust Deeds at St. Helens Congregational Church dated 2 February 1726, 22 March 1728,10 November 1742,11 December 1753, 11 June 1788.

53. Indenture, 7 October 1756 in the Town Hall, St. Helens.

54. The Journals of the House of Commons, Vol. XXVII, 17 January 1755.

55. Town Books, 2 March 1757.

56. £500 was added to this by shareholders.

57. Whitworth’s Manchester Magazine, 29 October and 5 November 1754.

58. Town Books, 18 October 1755.

59. Town Books, 4 July 1755. He was elected in the. place of Mr. Cribb, deceased, and he became Mayor in 1761.

60. In his will (dated 22 November 1753 and now in the Lancashire Record Office) John Ashton is referred to as “Merchant and Cheesemonger”.

The Liverpool papers (Williamson’s Liverpool Advertiser and the Liverpool Chronicle) for 10 August 1759, in the briefest of obituaries, merely notice the death of “an eminent merchant” renowned for his “probity, charity and abilities”. To have invested £9,000 within the space of six years, his eminence must have been considerable. An indication of the source of this great income maybe found in his membership of the Company of African merchants.

It is noteworthy that he was in the last years of his life when the Sankey project was afoot.

61. Berry bequeathed the silver cup, presented to him “by the Proprietors of the Sankey Brook Canal Navigation”, to his brother’s grandsons on their 25th birthdays. But significantly, if neither of them reached that age, the cup was to pass to Nicholas Ashton the son of John Ashton. A passage in the obituary notice of Nicholas Ashton (Liverpool Mercury, 21 December 1833) records that Nicholas “seemed to inherit the talent of his father, John Ashton, Esq., the first who carried into execution the project of a navigable canal in this kingdom.”

62. In 1785 Blackburne possessed only five shares in the Sankey Navigation (Second Codicil, dated 12 December 1785, to Will dated 17 June 1779, in the Lancashire Record Office).

63. The Journals of the House of Commons, Vol. XXVII, 16 December 1754.

64. Ibid., 17 December 1754.

65. Ibid., 7 February 1755.

66. Ibid., 17 January 1755.

67. This is remarkable; it is surprising that the owners of agricultural land, through which the southern part of the canal was cut, raised no protest.

For an example of the kind of protest voiced by agricultural interests, see T. S. Willan, op. cit., pp. 34-7, 45.

68. Geo. II, cap. 8: “An Act for making navigable the River or Brook called Sankey Brook and the Three several Branches thereof, from the River Mersey below Sankey Bridges, up to Boardman’s Stone Bridge on the South Branch, to Gerard’s Bridge on the Middle Branch thereof and to Penny Bridge on the North Branch thereof, all in the County Palatine of Lancaster; and also for adjusting the Measure of Coal to be brought down the said River or Brook, and sold within the Town of Liverpool, in the said County”. The Bill had passed the Commons on 3 March, and the Lords on 7 March. The Librarian of the House of Commons informs me that the minutes of the committee meetings have been lost, probably in the fire of 1834.

69. This important clause reads: “and to make such new Cuts, Canals, Trenches or Passages for Water, in upon, or through the Lands or Grounds adjoining or near unto the same River, or the Three several Branches aforesaid, or such Streams, Brooks or Watercourses, as aforesaid, or any of them, as they shall think proper and requisite, as well for the Navigation and Passage of Boats, Flats and other Vessels, as for the more convenient, easy and better carrying on and effecting of the same Undertaking.”

It may be compared with the clause in the Act of making the Douglas navigable (6 Geo. I, cap. 28):

“and to make any new or larger cuts, trenches or passages for water in upon or through the lands and grounds adjoining, or near unto the said River Douglas, alias Asland, streams, brooks and water course aforesaid or any of them as they the said Undertakers, their heirs and assigns shall think fit and proper for the Navigation . . .”

70. “That the said intended Navigation shall be carried on by a Cut or Canal to be made from Sankey Bridges or from some place near the same on the west or north-west side of the present course of the said River or Brook to some place above the Stone Bridge which is over the same and next above Holmemill Brook Mouth” (28 Geo. II, cap. 8). This clause could be used to explain away the making of a cut in the first stages (assuming work commenced at Sankey Bridges). It did not prevent the cut from being extended indefinitely beyond the mouth of Holmemill Brook (only “some place” is mentioned) but it certainly would convey the impression. Holmemill Brook being particularly stated, that the cut would terminate thereabouts. This would not have entailed a dead-water navigation.

71. Obituary notice in the Liverpool Mercury, 7 August 1812. There is something that rings true in this quotation, perhaps because of the information (found nowhere else) that work was begun on 5 September 1755 and that only one proprietor was in the secret. Whoever knew this would also know exactly what went on behind the scenes.

72. Geo. Ill, cap. 56, Cl. i, noted that free passage had been established to Gerard’s Bridge and Penny Bridge,

“except in the Time of Neap Tides, when the Navigation, as well of the same Brook as also of the River Mersey, from the Conflux of the said Brook with the same River, to a place called Fidler’s Ferry, is, for want of water, rendered impracticable”.

Vessels had been known to be stopped for a week (Journals o f the House o f Commons, Vol. XXIX, 13 February 1762).

73. E. A. Pratt, op. cit., p. 166. In arriving at a figure for compensation attention was to be given to land that “shall be Lessened in Value by not being flooded in Winter as Usuall”” (Articles of Arbitration, 1756, in the Estate Manager’s Office, Euston Station, London).

74. Journals of the House o f Commons, Vol. XXVI. Petition referred to committee 18 January, ordered 4 February, read 18 February, and evoked numerous crushing counter-petitions in late February and early March. ‘”

75. In August 1755 the Liverpool Common Council passed a resolution “that Mr. Wilbraham’s opinion be taken upon the two Orders of Council about the Sankey Navigation whether the Council are liable to pay the expenses of the survey or not” (Town Books, 6 August 1755). It is just possible that this may have been a first reaction to finding out what the real plan was.

But, on the other hand, the Council continued to support the Navigation and, on 2 March 1757, the money for the survey was paid to the Undertakers. Perhaps this resolution was just another example of thrift in local government which is not uncommon from time to time.

76. Town Books, 17 May 1756.

77. The distance from Sankey Bridges (where the canal joined the Brook via Sankey Lock) to Gerard’s Bridge, the farthest point reached by 1761.

78. Town Books, 1 May 1755. Berry’s presence on the Sankey for only two days a week throws considerable responsibility upon the lieutenants who carried out his instructions on the other five days. We know neither their names nor the degree of credit which is their due.

79. Insertion was repeated in Nos. 28 and 29.

80. Whitworth’s Manchester Magazine is completely silent after the advertisement of 1754, although, in the same month that the canal was opened as far as Haydock and Parr, this paper carried an account of a colliers’ riot at Prescot caused by a corn shortage (29 November 1757). This shortage was general throughout South Lancashire (S. Smiles, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 200) and probably led to difficulty in feeding the labour force on the canal. A weekly journal published in Warrington, close to the actual scene of operations, makes no mention of them in several copies which are still extant (Eyre’s Weekly Journal, 4, 11, 18 May, 29 June, 6, 13 July 1756). The Liverpool Chronicle did not commence publication until May 1757 and contains no reference to the Navigation until the advertisement of 4 November.

81. The County Archivist has informed the writer that the class of Deeds Enrolled is almost complete. There are, however, no deposits relating to the Douglas Navigation either. Yet the minutes of the Commissioners of the Douglas Navigation are available in Wigan Public Library. They contain several requests between 1738 and 1772 for the sheriff to impanel juries to assess the value of contested property, e.g. 12 March 1739; 23 February 1740; 30 April 1753; 16 January 1759.

82. In the Estate Manager’s Office, Euston Station, London.

83. Owners of land in Parr: Sarah Clayton of Liverpool, James Barton of Penwortham, Ralph Leigh of Lawton, James Orrell of Parr, William Aspinwall of Aughton, James Allenson of Windle (yeomen), Mary Rimmer of Speak (widow), James Naylor of Parr (smith), John Houghton of Parr (shoemaker), Richard Houghton of Parr (carpenter), Wm. Leafe of Sutton.

84. This led to an interesting case in the Courts in 1892. Owing to coal mining under the Canal, there had been occasional minor subsidences after 1850 which were repaired by the railway company as the owners of the Canal. After 1877 these subsidence’s became more serious – 18 feet in 12 months was complained of – and the railway company sued the coal owners. Judge Kekewich gave his judgment for the defence, holding that the right for which compensation had originally been fixed (and was paid annually) did not include the right to support by the subjacent minerals. This judgment was reversed on appeal (London and North Western Railway Company v. Evans, 1892). See The Times, 7 March and 8 November 1892.

85. The following calls were made: October 1754, £5; 1755, two calls of £7:10; 1756, five calls of £10; 1757, four calls of £10; 1758, three calls of £10; 1759, one call of £5; 1760, one call of £5; 1761, one call of £5. (A. P. Wadsworth and J. de L. Mann, op. cit., p. 221).

86. A later dispute over three shares bought by Edmund Rigby, a Liverpool ironmonger, who was “concerned in diverse other branches of trade”, throws a little light upon the type of person who invested in the Navigation (Chancery Records, Bills, PL 6, 84/3, 1766, preserved in the Public Record Office).

87. F. A. Bailey in TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 89, p. 43.

88. Sankey (between canal and brook), Bewsey, Hulme, Winwick, Hey, Bradley, Newton Common, Haydock, and the Old Double Locks at the fork between the north and west branches to Penny Bridge and Gerard’s Bridge respectively. Ln 1795 Aikin (op. cit., p. Ill) writes of eight single and two double locks. The lock at Fidler’s Ferry had been built, the Sankey Lock discontinued and a second double lock had been constructed at St. Helens at the point where the Ravenhead Branch ran at right angles to the southwards from the Gerard’s Bridge Branch. Aikin mentions that “The old lock by which it [the canal] at first communicated with the Sankey still remains but is seldom used, unless when a number of vessels are about entering from the Mersey at once, in which case some of the hindmost sail for the Sankey brook in order to get before the others”.

89. 2 Geo. Ill, cap. 56 (1762) gave powers to extend each arm by a further 1,200 yards (that is, up to 2,000 yards).

90. “A plan of the Sankey Navigation from the River Mersey into the Townships of Parr and Windle in the County of Lancaster. Survey in April and May 1759 by John Eyes and Thomas Gaskell and Plan by John Eyes in July 1763” at the Estate Manager’s Office, Euston Station, London.

91. 2 Geo. HI. cap. 56. The surveyor of this extension was John Eyes.

First mention is made of him in Liverpool in the 1720’s, which would make him somewhat older than Berry. He surveyed the proposed turnpike extensions in 1746 and 1753 (F. A. Bailey in TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 88, p. 191; Vol. 89, pp. 32-3.) He was connected with the survey of the Calder in 1740-1 and 1758, and he considered the possibilities of a Trent and Mersey Navigation in 1755 (R. Stewart-Brown, “Maps and Plans of Liverpool and District by the Eyes Family of Surveyors”, TRANSACTIONS, Vol. 62). He may have assisted Berry in the Sankey project but was certainly not its surveyor as asserted by Aikin (p. Ill) and Priestley (p. 561). He died in 1773.

92. 11 Geo. IV, cap. 1.