Written by PHILIP ANDREWS, B.A. Read 20 February 1969 to the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire

The only school in the village of Winwick today is the church of England primary school whose history, like so many others of its type, goes back about a century. The creation of this school marked the beginning of modern education for Winwick people and the end of the scope of this article, which seeks to tell the history of education in the village before 1872. This was haphazard, but surprisingly diverse for so small and insignificant a community.

On 4 March 1872, the present St Oswald’s Church of England School Winwick opened its doors at 9.30 a.m., and 81 children, 42 boys and 39 girls were admitted.

The doors were opened by ‘a newly certificated, and energetic master’, Walter Haskell, who spent the morning taking the names of the children, and classifying them according to their reading ability. No doubt, he also collected the fees: ‘for the children of farmers 4d. each child and for the cottagers 2d. each. The third and fourth child of any cottager from the same family will pay only Id. a week each and when more than four children attend the new schools from one cottage family, all beyond four will be free’.[1]

By the afternoon of 4 March 1872 another child had swelled the numbers on the roll to 82. When the school began its second week on 11 March, five more boys and three extra girls had raised the total of children to 90.

The building, still in use after nearly a century, was erected as a direct consequence of Forster’s Education Act of 1870 which allowed school boards to be elected to provide elementary education in those areas where the voluntary system was either non-existent or inadequate. In Winwick feeling on the choice

between a board school or a church school ran high. At a public meeting in the new school room on 16 March 1872 a leading member of the village, George Powlson, spoke warmly of the ‘spacious, well appointed School House’. He continued by expressing the wish ‘that it may long efficiently supply all the educational requirements of this neighbourhood, and so obviate the necessity for a School Board’, pointing out that this ‘will be the hearty wish of all who prefer the maintenance of parental authority to police surveillance, and of our old institutions to that craving for changes for changes sake, which is one of the curses of the day’.

The educational ideals of Powlson and his friends were realised in Winwick by the generosity of the rector of Winwick, the Rev. Canon F. G. Hopwood, who provided a piece of the glebe in the centre of the village upon which was built the school room at a cost of £656 Ils. 6d., ‘without’, as Powlson remarked, ‘either reference or trouble for any of us’.[2]

Hopwood continued to run the school at his own expense and according to his own lights, assisted only by the government grant which in the first year was £56. Indeed it was 1882 before the rector saw fit to place the school on a legal footing. Then, knowing that he intended to sell much of the glebe lands to the ecclesiastical commissioners, and wanting to make special provision for the land on which the church school was built, the trust of the school was conveyed to the ‘Archdeacon of Warrington and his successors’ so that the ‘piece or parcel of land now forming part of the glebeland belonging to me, as Rector of Winwick’ could be used for educational purposes.[3]

The history of the church of England school at Winwick, as told in its log books and managers’ minute books, is not remarkable. For nearly one hundred years it has served, some times better, sometimes worse, the community for which it was erected. Much more interesting, and much more elusive, is the history of education in Winwick before 1872. The diverse and inefficient system which the new Church school was built to replace, included a grammar school and two charity schools, all providing, in the nineteenth century at least, little more than elementary education for the boys and girls of the village. The scope of this article is the history of these schools from the beginning of the eighteenth century, until the grammar school ceased to exist in 1890 and the charity schools were replaced by the church school in 1872.

The most ancient school in Winwick in 1872 was the grammar school which, despite the small size of the village, enjoyed a great reputation in the years after its foundation in the sixteenth century.[4] Its rise to educational fame was rapid. About 1630, Adam Martindale wrote in his Life, ‘next I was placed under another school master at St. Helens Chapelle, who was brought up at the then famous school of Winwicke, whence multitudes were sent almost yearly to the university, but they were usually of good years before they were fitted, the method whereby they were taught, being very long.[5]

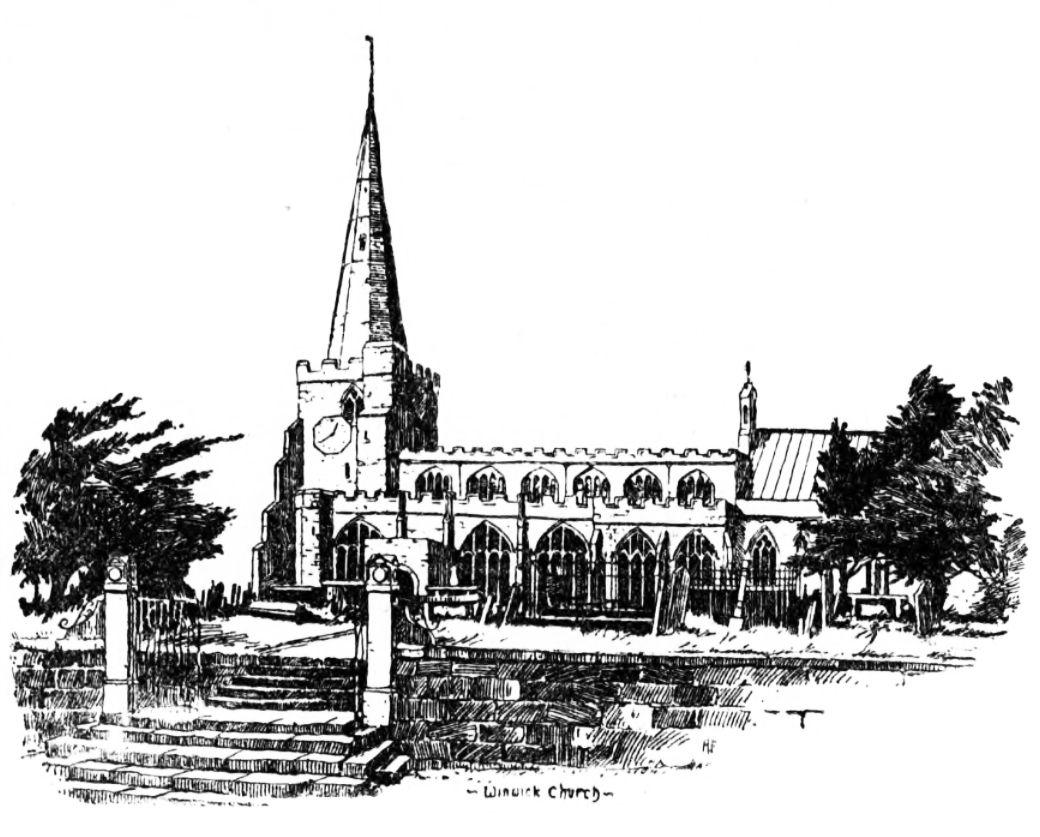

Other evidence exists to support this view of the school founded, it is thought, about 1547 by the Legh family of Lyme, who owned land in the ancient parish of Winwick, and a chantry chapel at Winwick church. Research by E. Axon, in the registers of Cauis College Cambridge shows that when Walter Kenyon, a pupil at Winwick grammar school and later rector of Bury, entered the College in 1563, he was the first pupil of any Lancashire Grammar School to do so. Eleven other boys entered the same college from Winwick school during the next hundred years, including one Thomas Bradshaw described as the ‘son of a carpenter’.[6] Since Cauis College was only one such institution in the ancient universities it will be seen, even from this slight evidence, that the claim made by the editor of the Life of Adam Martindale, that ‘the universities were then the only high road to literary distinction, and the school at Winwick one of their chief feeders from this part of the kingdom’, was probably correct.

The eighteenth century ‘Articles preparatory to visitation’ by the archdeacon regularly refer to the grammar school.[7] In 1778 they contain the statement that ‘there existed in Winwick a free school endowed principally by the Haydock family’. Eleven years later the entry was amplified, adding that the school was ‘for the whole parish to be instructed in Latin and Greek. It was founded by Peter Legh Esq., of Lyme. The Rector of Winwick is the sole Trustee. The revenue is about £35 per annum and is applied properly’. By the early nineteenth century, however, the school had lost its very high reputation and became little more than an elementary school.

The successive masters, most of them graduates, were usually at that time also the occasional curates at a local chapel of ease at Burtonwood or at Winwick church itself. This dual employ ment must have been made necessary by the financial straits of the clerics, but it must have been difficult to have been both parson and schoolmaster at the same time. The other main reason for the decline probably lies in the rise of nearby gram mar schools, and the lack of enough suitable grammar school candidates from Winwick and district.

In 1801, the first census recorded that the master, the Rev. Dr Prince, took 36 ‘gentlemen boarders’, but 27 years later the charity commissioners reported, ‘the School had been for several weeks shut up, and Mr Williamson (the master) was residing in a place 20 miles distant without ever coming to Winwick. . . . The present master has never taken boarders and the number of the day scholars under him appeared at no period to have exceeded 5’.[8]

This grim picture is confirmed by the rector’s reply to the 1825 ‘Articles Preparatory to Visitation’, in which he recorded ‘a free grammar school, endowed, it is almost without scholars.’ The schools commissioners’ report in 1869 was equally bad. It recorded 17 boarders and 10 day boys aged between 6 and 16, each paying £4. 4s. Od. p.a. with an extra £1. Is. Od. for modern languages, music and drawing. The report underlined the sorry state of affairs. ‘Few remain after 15, and none go to the University. There is hardly anything to be remarked or suggested regarding this foundation. It is of little or no service to the place where it stands.’[9]

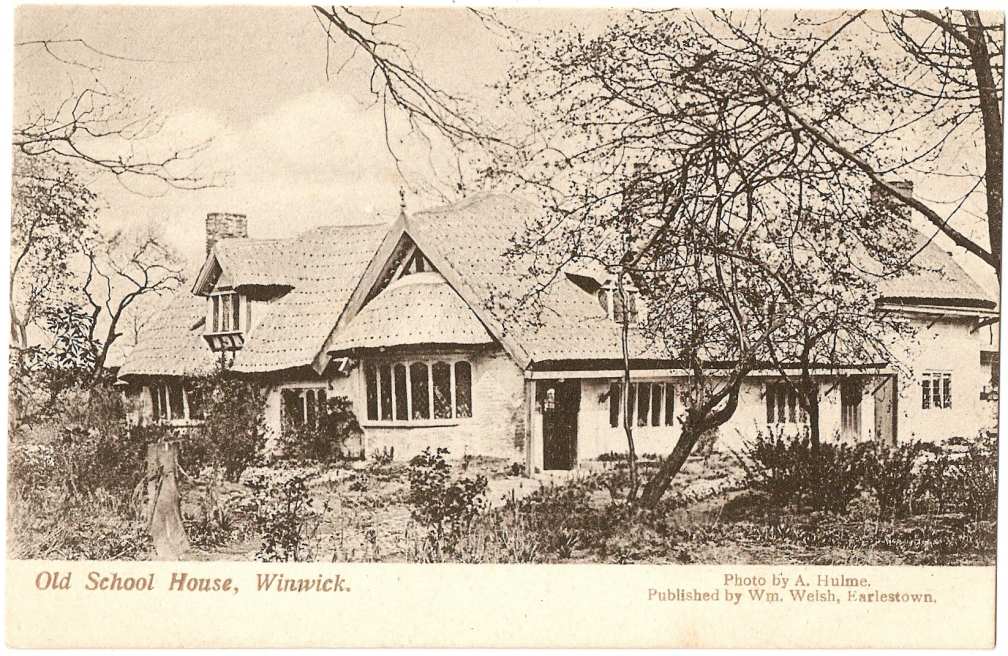

The school struggled on until 1890, when it was closed. Its assets, such as the school house and school land, were sold and the proceeds used to form the Winwick Educational Foundation, which still exists today to give financial help to educational projects in the village.

The brief history of the decline of Winwick Grammar School seems to show that during the latter part of the eighteenth and in the nineteenth centuries the so-called grammar school was only providing an elementary education for the majority of its pupils.

The ordinary education, however, of most of the boys and girls in Winwick was provided by the charity schools.

The earliest reference to a school, other than the Grammar or Free school, in Winwick occurs in Notitia Cestriensis where Bishop Gastrell noted, in 1719, ‘a Charity School lately built for 20 poor children’.[10]

This must have been a type of charity school ‘established to give instruction in reading the Bible and catechism and sometimes in writing and casting accounts’.[11] The evidence for this however is very slight, for nothing else is known of this school in Winwick in the early eighteenth century. No trust deeds of the school survive, nor are they referred to in documents that still exist, and the records of S.P.C.K. which exist to 1735 contain no reference to a charity school at Win wick, though the society often supervised such schools. These facts possibly point to a school established either by public subscription or by the beneficence of a local wealthy man. In Winwick such a person existed, the rector. M. G. Jones comments, with reference to the foundation of country schools, ‘the interest and enthusiasm of the parish clergy’ was vital; ‘they initiated the movement and managed and inspected the schools they set up’. Winwick could certainly fit into this pattern.

Further evidence concerning the eighteenth century charity school in Winwick is difficult to find. The teachers there had no qualification or status, and so no record of them occurs in the lists of teachers’ licences issued by the bishop of Chester, now in the Cheshire Record Office. Throughout the century only the names of the successive masters of the grammar school appear in these records, with one exception. In 1716, along with the name of the grammar school master, the name of William Dunbabbin is recorded. Several explanations of this are of course possible, including the fact that he could have been an usher in an enlarged grammar school. It is more likely that here, for the one and only time and perhaps by mistake, lies the name of the charity schoolmaster, especially as William Dunbabbin is contemporaneously recorded as parish clerk.

In the later eighteenth century, one of the sources of information about the charity schools is the Articles Preparatory to Visitation. In 1778 the rector’s reply made a bald reference to ‘a charity school maintained by the Rector’, thus supporting the assumption made earlier that in Winwick the Rector was the rich man capable of founding and maintaining a charity school.

In 1789 further details were given; ‘There is a voluntary Charity school in Winwick .’or the children of the poor supported by the expense of the Rector. They are taught reading and writing and are likewise instructed on Sundays in the same measure on the plan of a Sunday school’. In 1811, however, there is important new evidence. The rector remarked ‘There are three voluntary schools in the village of Winwick, one for boys and two for girls supported chiefly by myself and my family’. The identity of the boys’ school and one of the girls’ schools can be established, but no evidence, except for this statement, has come to light for the existence of a second girls’ school.

The history of the boys’ school can be fairly reliably traced from about 1810 until it was superseded by the new 1872 school, although there was some sort of charity school in Winwick before 1810, as we have seen. It was this boys’ school to which the then rector, the Rev. J. J. Hornby, referred when he applied to the National Society, formed in 1811 by Andrew Bell, for terms of union. In a letter from Winwick Rectory, dated 23 January 1815, the Rev. Mr Hornby wrote as follows to the Society:

I am instructed to apply to yourself for the purpose of connecting a school of mine in Winwick with the National Institution. This school is on a scale to receive one hundred boys—it is supported by my own expense, with a permission to the master to receive thirty boys at a salary. The school is just set on foot, and the Madras system of teaching is adopted. The children are instructed in the Liturgy and Catechism of the Established Church of England, and attend divine service in their Parish Church as far as same is practicable. Nor are religious tracts admitted, but are such as are contained in the catalogue of the Society for promoting Christian Knowledge.[12]

No answer has been found to this letter, but the school was obviously accepted as the association between the present school and the National Society still exists.

In 1815 the Annual Report of the National Society recorded a school at Winwick for 70 boys which would seem to be a com promise between the number of pupils the school was capable of accommodating and the number that actually attended. In return for union with the society a subscription was expected from the school, which in the case of Winwick meant a donation by the rector, who became a Life Member of the society on payment of a subscription of £10. In his replies to the questions contained in the Articles Preparatory to Visitation of 1825, the rector duly recorded ‘a National school at which about 60 boys attend’. In a masterly understatement the rector explained his own part in education in the village: to a certain degree, personally superintend my National School, and in fact it is maintained by me and is entirely under my discretion’. Atten dance must have been very erratic, and this may go some way to explain the widely divergent figures given.

In 1825, for example, A charity school for girls was first mentioned in the 1811 Articles Preparatory to Visitation, but surprisingly no mention was made of such a school in the replies of 1825. This surely cannot mean the school had closed before 1825. It might be that only boys’ schools were enquired about or that the answers were

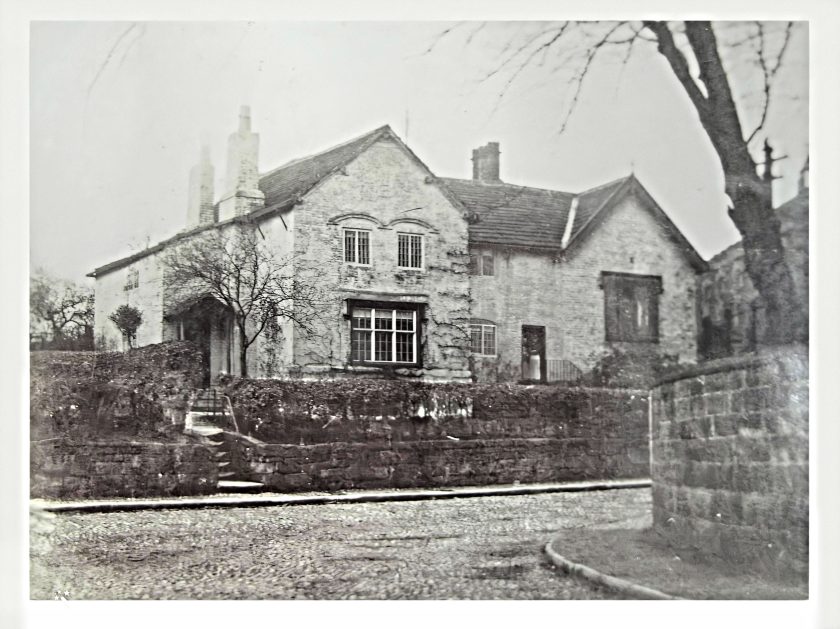

“Figure 12 THE GIRL’S CHARITY SCHOOL, WINWICK”

either inadequately given or inaccurately written down. The girls’ school certainly seems to have been on a very firm footing by 1825; indeed a book of regulations, Rules for the school of industry and piety at Winwick, was printed in 1809 for the girls’ school. The School of Industry referred to in the title was simply the girls’ charity school under another name.[13] Proof of this may be found in the obituary notice of an old Winwick character, Mrs Sarah Hodgkiss (nee Byrom) in 1940, which recalled the many changes that the deceased had seen during her eighty-one years of life, and continued:

She was fond of recounting stories of the old Dame School, and particularly of Miss Whitehurst and Miss Christian who were teachers there. According to her story the scholars who had misbehaved had to wear round their necks a card on which was indicated the nature of the offence and also were obliged to stand up in the Parish church on Sunday still wearing it.[14]

The same practice is recorded in the Rules for the school of industry; ‘Black tickets with the name of different faults. . . will be given each day to those who deserve them to be worn round the neck. The tickets to be returned to the school mistress the following morning’. Other rules, addressed to girls, offer additional proof that the girls’ charity school was called the school of industry.

Whether the girls’ charity school at Winwick was a school of industry, as understood by contemporaries, is uncertain. True schools of industry were working schools with a short period daily in which the children learned to read, but otherwise the week was given over to work, and Sundays to learning. There was little attempt to relate the work of the children to their book learning. Pitt’s unsuccessful Bill of 1795 would have set up a national system of schools on the lines of the schools of industry, but in the voluntary system that did emerge these schools were more numerous in the towns, though they did also exist in the rural areas like Winwick.

The book of Rules for the school of industry and piety at Winwick, intended to regulate behaviour at the girls’ charity school, is of especial interest. It begins by addressing the children:

This little book written for your improvement, contains an explanation of the important table of Virtues and Vices hung in your school, as they will be daily and faithfully taught; you cannot plead ignorance for the commission of any fault, but must accept and submit to its due and wholesome punishment . . . it contains likewise all the rules of a school in which, when you enter, consider it as a type or pattern of that great school, the World.

The Virtues referred to were numerous, and included ‘Piety’, ‘Truth’, ‘Meekness’, ‘Prudence’, and ‘Modesty’, described as ‘the best ornament a female can have’. The Vices included ‘Profaneness’, ‘Anger’, ‘Ill nature’, and ‘Imprudence and Tattling’. ‘Wastefulness’ was defined: ‘If you wear your Sunday clothes every day, if you go with holes in your stockings . . . if you dirty or tear your books, you will be charged with Waste fulness. .. .’The vice of ‘Boldness’ was described thus: ‘If you are seen romping anywhere with men or boys’.

Attention was next focused on the parents of the girls attending the school. Tn these times of difficulty and pressure’ it opens, referring to the Napoleonic Wars, ‘when you find it hard to pay for the education of your children, you will be sensible of the great advantage which they and you derive from this institution.’ The exhortation continues with strangely modern remarks on the role of the parents:

Every attention will be paid to the instruction of the children both by the mistresses and the visitors of this school, but it cannot be supposed that these efforts will be successful unless supported by those of the parents. It must, therefore, be earnestly requested that the children may not be detained at home, except in the cases of the most absolute necessity. The children of those parents who do not attend to this request must unavoidably be dis missed from the school.

The third section of the booklet deals with the rules of the school. From April to October the school hours were 8.30 a.m. to noon, and in the afternoon the children returned at 1.30 p.m. and worked until 5 p.m. These hours were reduced to a 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. day in the winter months. Holidays consisted of a month at Christmas and a similar length of time at hay harvest.

On Sundays the girls had to be in school at 9 a.m. and were free to go only after matins in the parish church. Absence was punished, as far as was possible, by the system of fines: ‘each girl who is absent without some very sufficient excuse, to be set down in the forfeit book for one farthing’. On Sundays the fine for absence rose to one half-penny. Discipline was rigidly kept. ‘A Character Book will be kept in which the faults and merits of each girl will daily be faithfully recorded. Those girls who at the end of term appear by the book to be most deserving, will be placed at the head of the school, and will be rewarded accordingly; they will also receive a Red Ticket to be kept by them, entitled General Good Behaviour’.

As well as the black tickets already referred to by Mrs Hodgkiss, tickets were also issued daily, as well as termly, for individual achievements rather than as a reminder of misdemeanours: ‘Red Tickets with the names of every different Virtue in the above table will be given each day to those girls who deserve them, to be worn round the neck’.

Prizes were offered annually for catechism, attention, industry, neatness and other virtues.

Punishment was severe by modern standards, as these examples show:

‘Any girl who tells a falsity to sit by herself with a Red Label on her Gown, on which is written, “Lying Lips are an Abomination to the Lord”’.

‘Any girl who is guilty of dishonesty, not to be trusted with anything of Value but to have her pocket searched publicly every time she goes out of school till she appears sensible of, and penitent for her Fault’.

Punishments seem often to have been entirely retributive, with no thought of correction:

‘Any girl who is charged with Impiety or Profaneness to sit in the naughty corner till school is over and not to speak or be spoken to . . .’

Another punishment prevented the child from mending her ways:

‘Any girl who is charged with great Idleness to have her hands tied as long as the mistress deems proper . . .’

On a more personal note, the rules required each girl to come to school ‘with her hands, face and head washed, her hair cut quite short with combs in it, her clothes clean and tidily put on, without earings or any other finery’.

In addition, ‘Each girl is to find her own work bag and Thread Case, Scissors and Thimble and to bring her Book of Rules with her every day’.

As the girls grew up they had to take a more responsible part in school life. ‘One of the four eldest girls,’ the rule book continued, ‘to be the servant for one week by turns, and to return on Saturday to clean the school room, for which she will receive two pence. The rest to have a holiday on Saturday’.

Eventually, at the age of 12 or 13, the girls had to consider looking for a job, at first possibly on a part-time basis. As the rule book decrees:

‘When the girls can work sufficiently well to be employed by others they will receive 9d. in every shilling they earn, the rest to be employed in buying working materials, books, and such necessary articles for the school’.

Most girls presumably went into service, and each girl ‘who has conducted herself well, when she leaves the school will receive from the ladies a certificate of her good character to take with her into the world’.

Furthermore, a primitive youth employment service was in operation, at any rate for the chosen few: ‘Care will be taken to procure a proper station in life for those girls who, having conducted themselves particularly well, remain at the school until they are of an age to go into service’.

Evidence about the numbers of children attending these schools, about the pupils themselves or about those who taught them, is sparse. Two helpful sources are, however, available. A copy of the 1801 Census for Winwick village exists in full detail, and in the Lancashire record office is a Speculum of the inhabitants of the village of Winwick written by the curate of the parish in 1851.[15]

Purely numerically, the 1801 Census records 121 children of school age, that is to say between 5 and 13, and 73 under the age of 5 years, a total of 194 children out of a population of 573. Fifty years later, the Speculum, which does not pretend to be as exhaustive as a census, records 75 children of school age, and another 31 under the age of 5. The population of the village in 1851 according to the Census for that year was 469.

The Census, full of details about ages and occupations, has little to say about education, but the Speculum is less statistical, and more colloquial. The author, the Rev. Septimus Pigott, recorded, along with names and ages, whether each person could read, whether the household possessed a Bible, and whether family prayers were conducted, and he also added his own personal comments, some complimentary, some derogatory, upon the villagers. Against the name of each child of school age he recorded the school which that child was attending. Most of the Winwick children were of course receiving their education at the grammar school, the boys’ charity school, called by Pigott ‘the Calvert school’ after the name of the master in 1851, Peter Calvert, or the girls’ charity school, called by the Speculum ‘the Hornby school’ after the Hornby sisters who were the teachers there.

The total number of children at the grammar school in 1851 was not stated by the author of the Speculum, but the report of charity commissioners for 1869 recorded only 27 pupils, 10 day boys and 17 boarders. Only one boy in the village of Winwick was enumerated by Pigott as attending the grammar school, Charles Hatton, the eight year old son of James Hatton, whom Pigott calls a ‘course farmer’, and with whom Pigott lived. The curate remarked, T lodge with J.H. and am very comfortable’.

The other grammar school boys must have been from outside the village.

The bulk of the Winwick children are recorded as attending ‘the Hornby School’ and the ‘Calvert School’. Senior among the boys was John Warburton, whose father was a joiner, described as ‘Head boy at Calverts’. Twenty boys are specifically mentioned as attending Calvert’s including John and Robert Gorse, who were twins, and eleven year old George Sankey, described as ‘a very steady boy’. The Kerfoot family had three boys at the same time at the school, Peter age 13, George age 8, and Thomas 7. Of their mother, Hannah Kerfoot, Pigott wrote, ‘she promises to come to Holy Communion’, and then, at a slightly later date added, ‘P.S. Mrs Kerfoot is now a regular communicant, Laus Deo’. Jonathan Wainwright lived with his grandmother, who ‘does not know her age’, but Pigott estimated this as 80 years.

Other pupils at Calvert’s School included the three Gorse brothers, who ‘live by the [Sankey] Canal’, the two sons of the labourer John Dean, and John Johnson, whose father George, a widower aged 35 years in 1851, is noted as being unable to read.

Lucy, the seven year old daughter of parish clerk Thomas Warburton, attended the Hornby School, along with Eileen Ambler, whose mother was described by Pigott in his usual style with the comment, ‘seems well read in the Scriptures,—sensitive religious woman with a fine heart and benevolent spirit—good at need’.

Similarly, the family of eight year old Alice Hamblett, was described, ‘people with some good in them’. Jane Williams, one of the senior girls at the Hornby school, Pigott regarded as ‘a very good girl’, while the Pollitts, whose daughters Elizabeth and Ann attended the girls’ school, Pigott considered ‘a very respectable industrious dull family,—that fear God’. Esther and Sarah Milnes, whose father James, a labourer, had died, were two daughters in a family of eight. Five of their brothers and sisters were already at work, all of them in private service, a calling which the Rides of the Hornby school singled out as being especially suitable for the young ladies educated there.

Almost all the children in Winwick in 1851 attended one or other of the village charity schools, but eight received their education elsewhere. John Jackson is recorded as ‘educated at the Blue School, Warrington’, Isaac Clark at ‘the Blue School’.

John Tomkinson attended the Collegiate Institute, Liverpool, and Mary Pennington ‘the training school’, possibly that for teachers in Warrington. Of ‘Miss Greenings’ School nr. Middleton’, the Gerrard Chapel school’, or ‘Miss Higginson’s School’, all mentioned by Pigott, nothing is known (though there is a Myddleton township in Winwick parish and a Gerrard Chapel in Winwick Church), but three different Winwick children were educated there. Lastly, Anne Appleton, the youngest of six children of a shopkeeper, was mentioned as deaf and dumb and attended ‘the Institution for the Deaf and Dumb in Manchester’.

Information about the teachers, as well as the pupils, can be found. A good deal is known and has already been published about the grammar school masters of Winwick. Beaumont gives what he claims to be a complete list from the school’s foundation in 1547 to the late-nineteenth century when he was writing.[16] These teachers were qualified, usually graduates, and their names appear in official records such as the lists of teachers licenced by the bishop of Chester in his see. In the case of the grammar school masters, therefore, the Census and Speculum add little. The Census does not even indicate that the Rev. Dr Prince was the headmaster of the grammar school in 1801; other sources tell us that he was. It does yield the information that he was living with his wife and six servants, but as yet no children.

His age is not recorded. In the Speculum of fifty years later again no detail was recorded. The grammar school master by this date was the Rev. Samuel Burnell who is simply stated to be living at the school with his wife, son, brother and three servants.

Evidence about the teachers at the charity schools is harder to find. The evidence of the Census confirms that in 1801 there were three schools in Winwick, a grammar school and two charity schools, and three teachers, two men and a woman. As well as Dr Prince at the grammar school, it recorded one Eileen Dutton, aged 50, probably a widow, as ‘School Mrs.’, and Elizabeth Dutton, aged 25, who lived with her and who must have been her daughter, as ‘assistant’. Thomas Walker, aged 36, a married man with six children aged between 2 and 12, is described in the census as ‘Schoolmaster’. This is confirmed by the inscription of his grave stone in Winwick Churchyard, ‘Village schoolmaster in Winwick 37 years, viz., from 1789 1826’.

Walker’s predecessor may have been Robert Grice, because when his wife Mary was buried at Winwick on 28 November 1812 a note was added to the inscription in the burial register that Mary’s husband, Robert, had been ‘late school master of Winwick’. No other evidence about other eighteenth century charity school teachers in Winwick has so far come to light.

By 1851, when the Speculum was written, the master at the boys’ school was Peter Calvert, born in 1819, by this time married to his second wife Prudence. Pigott described them as, ‘Both Thoroughly excellent’, and Peter as ‘a good schoolmaster, and I believe a good man’. Calvert, who came from Bury where his father was a whitesmith, attended Chester Diocesan Training College in the 1840s, the first teacher at either charity school, so far as is known, who underwent teacher training,[17] The Speculum called the girls’ charity school ‘the Hornby school’ because it was run by the three Hornby spinster sisters, Frances, Louisa, and Henrietta, who in 1851 were aged 64, 62 and 57 respectively. They were daughters of the Rev. Geoffrey Hornby, the rector of Winwick who died in 1812. They did not live at the school but at Broad Oak cottage, near the Church, where they had seven servants. They are buried in Winwick Churchyard. The Speculum also records some other isolated facts concerning school teachers which are, as yet, difficult to fit in the established pattern. Mrs Sarah Potter, aged 78 in 1851, is mentioned as ‘formerlly schoolmistress’, and her daughter Mary, married to Thomas Rigby, is also described as ‘school- mistress’[17].

They were obviously an educated family for Rigby is described as possessing ‘many nice books, e.g. Slade on the Psalms, and Sturm’s Reflections’. James Darling, a farmer’s son from Winwick, aged in 1851 28 years, is recorded as a ‘clergyman has a curacy in Kent, formerly schoolmaster at Winwick’.

The schools which had served Winwick in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were not, however, to be satisfactory for the post-Forster era. The grammar school was on the point of collapse, the boys’ school was housed in an old unsatisfactory building by the church, and the girls’ in a sixteenth-century cottage which was very beautiful but not suitable as a school, while the teaching and equipment of all three left much to be desired by the standards envisaged by the 1870 reformers.

Faced with a board school as the alternative, however, the rector of Winwick provided what both he and his villagers wanted, a church of England School which replaced the three schools in 1870 and which has provided for the education of the young children of Winwick up to the present day.

- The Log Book, volume I, of St Oswald’s church of England school, Myddleton Lane, Winwick, Warrington, Lancashire. The Log Book, three volumes in all covering the years 1872 to the present, are kept at the school and were made available to the author by the headmaster.

- Warrington Guardian, Saturday 16 March 1872.

- The trust deed of St Oswald’s school. Win wick, 1882, is kept by H. Greenall Ltd. (solicitors), Warrington.

- No history of Winwick grammar school exists. Apart from brief references in general works on Lancashire or Lancashire schools, the main printed infor mation about the school is to be found in W. Beaumont, Winwick, its history and antiquities (2nd. edn. 1878) (hereafter Beaumont).

- The Life of Adam Martindale, ed. R. Parkinson, Chetham Society IV (1845), p. 12.

- E. Axon, ‘Lancashire and Cheshire admissions to Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge 1558-1678’, Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society VI (1888), pp. 74-98.

- Articles preparatory to visitation concerning Winwick exist in the Cheshire county record office for the years 1778, 1811, 1821 and 1825. These documents contain only the answers given by the rector but among the records of St Oswald’s church Winwick, is a copy of both the archdeacon’s questions and the incumbent’s answers for 1789.

- Report of charity commissioners (1828), quoted in Beaumont, p. 100.

- Report of schools commissioner (1869), quoted in Beaumont, p. 101.

- Notitia cestriensis, ed. F. R. Raines (1845, 1849-50), II part 2 (Lancashire), p. 266.

- M. G. Jones, The charity school movement (1938), pp. 5, 65.

- The library of the National Society Westminster, London, contains a small file on Winwick School. The only document contained therein referring to the period before 1872 is the letter quoted. The very brief information from the Annual Report of the National Society for 1815, 1816 and 1825 was gained from the printed copies in the same library, the rector reported 60 boys in his school; a year later the Annual Report of the National Society gave the number of boys at the day school as 23. There was also a Sunday school teaching 55 boys.

- Warrington local history library, Rules of the school of industry anil piety at Winwick (1809).

- Warrington Guardian, 9 March 1940.

- A manuscript copy of the Census made in 1801 for the village of Winwick, recording by name every inhabitant, and details such as age and occupation, is in the possession of the rector and wardens of St Oswald’s church, Winwick, and is housed there among the muniments. The author acts as archivist to these documents. A Speculum of the inhabitants of Winwick, written by the Rev. Septimus Pigott (1851) is preserved in the Lancashire Record Office (hereafter the Speculum).

- Beaumont, pp. 91-102.

- The papers of Peter Calvert have been kindly lent to the author by his great grandson, Lt Col Peter Calvert of London. These refer to Calvert’s early life in Bury, his teacher training in Chester, and his work as schoolmaster at Winwick, but have not yet been thoroughly studied.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is most grateful to all those people who have made material avail able to him, but especially to Mr M. Boardman and Mr L. Johnson of Winwick school, the rector and wardens of St Oswald’s church Winwick, and Mr J. Naylor of H. Greenall Ltd. (solicitors), Warrington.