By the Rev. W. A. Wickham: 28th November 1907

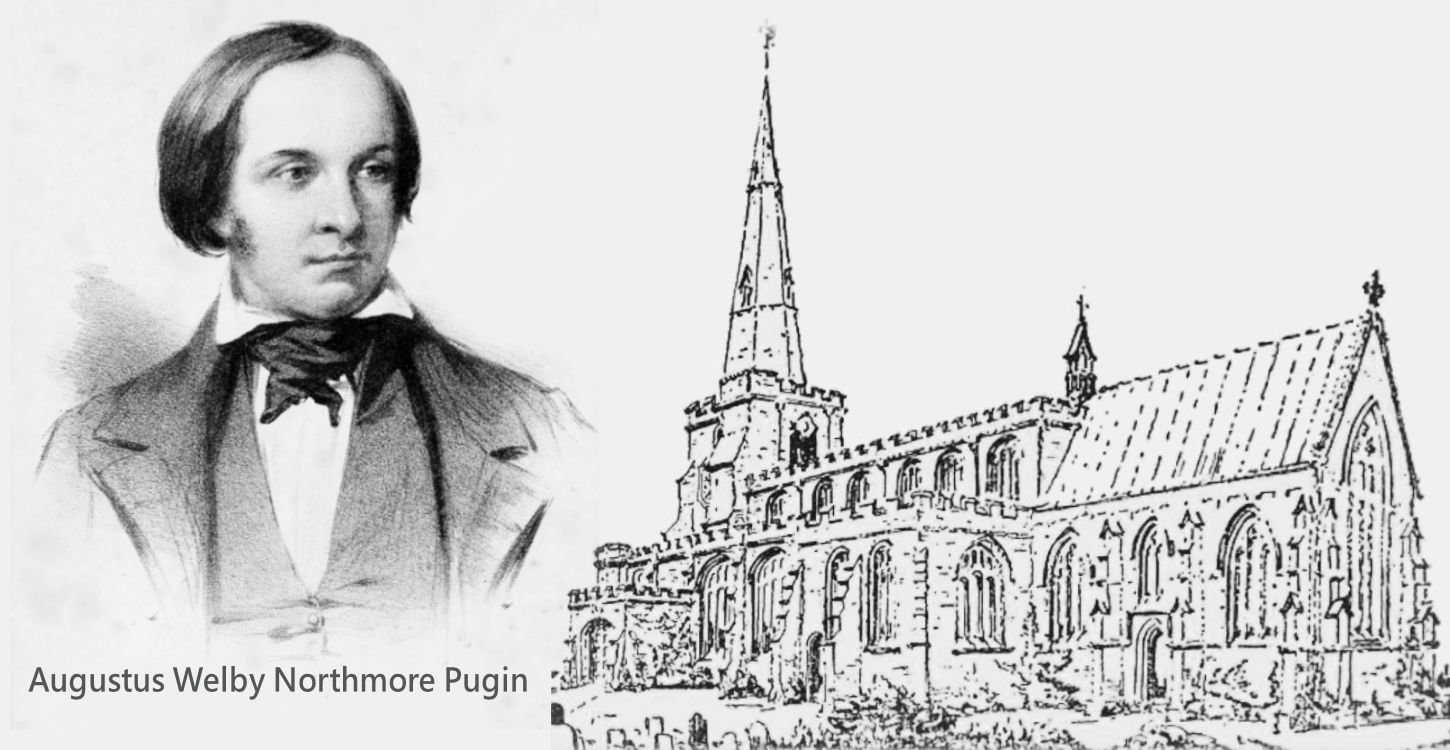

Perhaps no man set so deep a mark, directly and indirectly, upon the English church architecture of the nineteenth century as Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, of whom Dean Stanley spoke as “that splendid, if eccentric, genius, who gave himself, though not with undivided love, to the service of another Communion” (qu. Scott, Recollections, p. 390). Ruskin, indeed, sneered at Pugin’s genius, and spoke of him (Stones of Venice, Append. 12; qu. Ferrey, Recollections, p. 164) as “one of the smallest possible or conceivable architects … he will never design so much as a pix or a piscina thoroughly well.” But it is almost impossible to read Ruskin’s Lamp of Truth, and to compare it with Pugin’s True Principles, written eight years earlier, without concluding that at least Ruskin was greatly indebted to Pugin. The many thoughts and even expressions common to the two books might, had the later writer been any other than Ruskin, have made him liable to the charge of plagiarism.

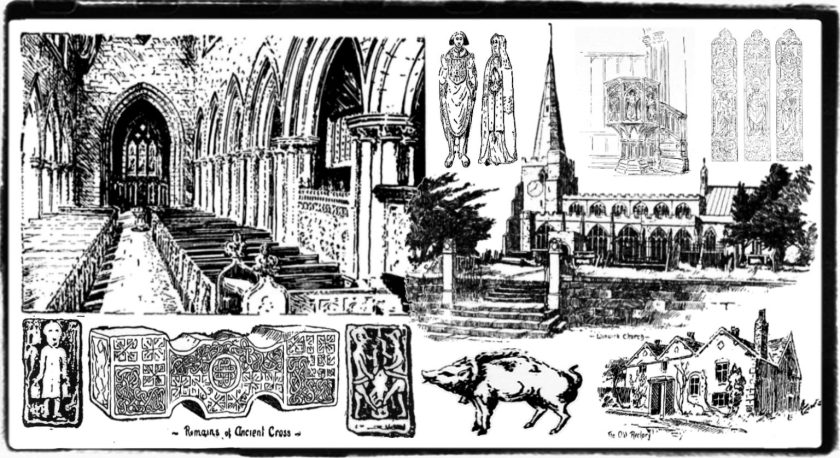

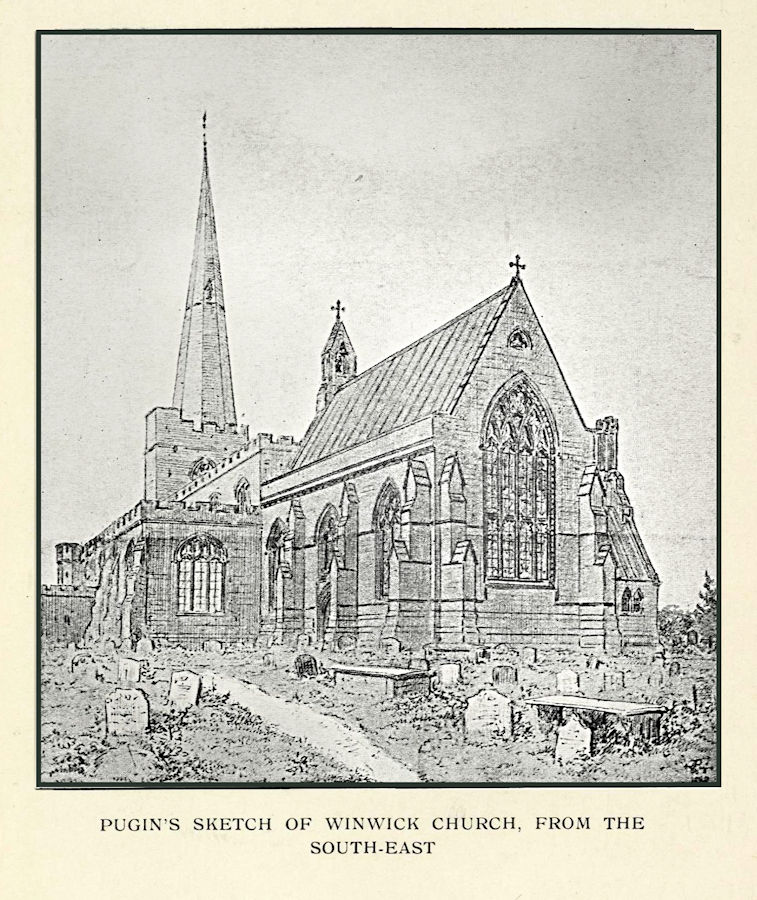

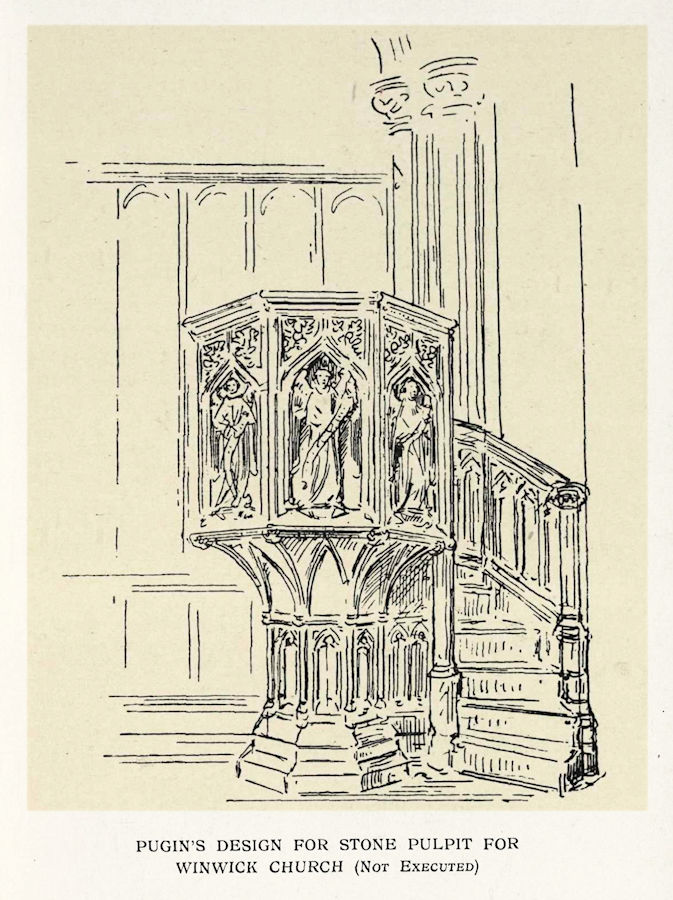

Pugin inherited much of his genius from his father (Augustus). He transmitted some of it to his son (Edward Welby). He joined the Roman Church when about twenty-three. He died insane at forty. It is interesting to think of what Pugin’s career would probably have been had he remained a member of the English Church, and lived, like Sir Gilbert Scott, who was some seven months his senior, to threescore years and eight. This was not to be. His life was too. strenuous and highly strung to last long. “Being made perfect in a little while he fulfilled long years” (Wisdom, iv. 13) and owing to his change of faith he lost his opportunity of doing much work, directly, for the English Church, though his indirect influence upon her buildings was enormous. Of Sir Gilbert Scott Dean Stanley (loc. cit.) spoke as “the most famous builder of this generation … no name within the last thirty years has been so widely impressed on the edifices of Great Britain, past and present, as that of Gilbert Scott.” Scott, again, was the master of Street, Bodley, and a host of others. But Scott himself, in a passage in his Recollections (p. 88), which it is not easy to forget when once one has read it, attributed his own “awakening” more especially to Pugin. Yet in the list of Pugin’s works given in Ferrey’s Recollections (p. 274) I think there are less than half-a-dozen for the English Church. Now it so happens that what Ferrey considered to be “one of his finest works’’ is the re-building of the chancel of Winwick Church, in the diocese of Liverpool. This was begun in 1847 and finished in 1848, nearly four years before Pugin’s untimely death in 1852.

The Rector of Winwick at that time was the Rev. J. J. Hornby. He was born in 1777, was instituted to Winwick in 1812 (the year of Pugin’s birth), and died in 1855 in his seventy-eighth year. He was therefore about sixty-nine years of age when he employed Pugin, who was then about thirty-four. He was Squire of Winwick as well as Rector and was closely connected with the family of the Earl of Derby, his patron. He had already done much for Winwick Church before he touched the chancel, and the contract for the restoration of the well-known inscription on the south aisle of the church, which, together with the balance sheet, is to be found printed in the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Notes, vol. ii. 1886, shows at once the Rector’s conservative care, his thoroughness, and his generosity. He was evidently a capital man of business, despite his being a parson, or in consequence of it. How he met with Pugin I am not able to say, but to have employed him to rebuild his chancel in 1847 seems to show considerable courage.

Newman went over to Rome in 1845. Many others went too. Pugin had gone about ten years earlier and was now a very marked man. Party feeling ran high. It was “a time of distress, of which few analogous situations in our days can give the measure” (Dean Church, Oxford Movement, p. 343). Ferrey tells (p. 186) how in the early ’forties Pugin, invited by a friendly Fellow, prepared an admirable design for some new buildings at Balliol College, Oxford. But it was at once vetoed by the then Master, Dr Jenkyns, on the sole ground of Pugin’s faith, and as a matter of fact, apart from the Magdalen Gateway, he did almost nothing at Oxford (Ferrey, p. 189), whilst at Cambridge his sole work was the restoration of Jesus Chapel (Ferrey, p. 275).

Rector Hornby was superior to anti-Roman prejudice of that sort. He had made up his mind that Pugin was the best man for the work. He was, apparently, the sole paymaster, and having to pay the piper, he both chose the piper and insisted upon having a considerable say in the calling of the tune. He might, perhaps, best be described as an early Tractarian. He was quite determined that Pugin should give him plenty of room at each end of the Holy Table [52 – 531]. Yet in his sermon at the opening of the chancel he could say, “as the capital feature of this holiest place of the church stands the Altar of our Eucharist Sacrifice, speaking as with the tongue of angels that the way which is consecrated for us thither is ‘ by the Blood of Jesus’” [85]. He was careful not to hurt the susceptibilities of his people, but he was accustomed to have his own way.

Please note that Figures within square brackets [123] refer to the Winwick MSS.; the date of the letter is added where possible. References to Ferrey’s Recollections are given thus – Ferrey, p.

It so happens that in the archives of the Parish of Winwick there is a volume in which has been carefully preserved the greater part of the correspondence between Pugin and Rector Hornby concerning the rebuilding of the Winwick Chancel.

Through the kindness of the present Rector, Canon Penrhyn, I am allowed to give considerable extracts from it.

The book contains letters from the builder and others. The builder was George Myers, whom Pugin trusted implicitly, and who did nearly all his work. His few letters are not without interest, as e.g. [27, May 10, 1847] when he writes to the Rector: “Matthew [Piddock, Clerk of Works] writes to me that there is more earth than he knows where to take it to. I only write these few lines to say that you are most likely aware that the earth should not be taken out of the consecrated ground, as I have at different times seen such things done, which has caused a very great noise. You will please excuse me in this as I am sure you will know better what to do than I can tell you, but sometimes things slip through.”

The Rector’s letters to Pugin are of great interest. The standard life of Pugin is his Recollections, 1861, by Benjamin Ferrey, his fellow-pupil in the elder Pugin’s office. It is an irritating book in some respects, but the only one. On page 234 he says:-

In order to appreciate the peculiarities of his mind, there needs a faithful record of his sayings and doings in connexion with the many distinguished employers.

The materials for such a biography are wanting, as Pugin unfortunately destroyed all letters received during the early years of his practice.

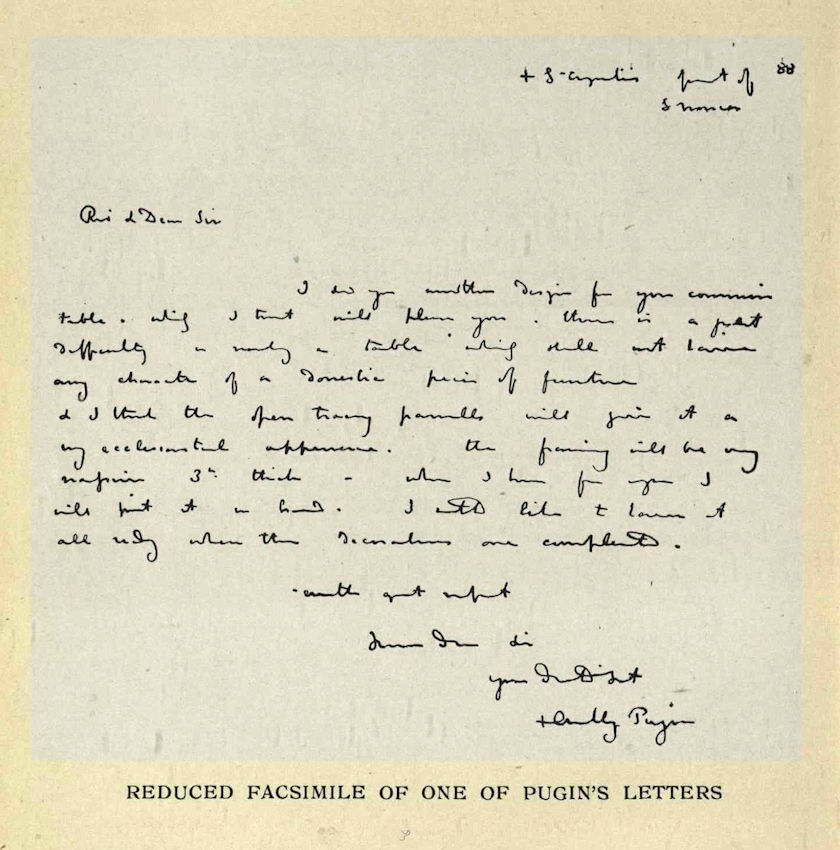

“The great value of the Winwick Letters is thus apparent. There are fifty-three written by Pugin, and some sketches and plans from his hand. Pugin’s letters and some of his sketches are upon blue paper, measuring 8 inches by 10 inches. They are remarkably neat, but, at first sight, anything but legible. He evidently wrote fast, and with a very fine pen.

Fortunately, there are no abbreviations, very few unnecessary strokes, and there is a good space between the words. There are very few stops, and often no capital letter after what a full stop should be. There are sometimes wide, meaningless intervals between words, and sometimes what looks like a full stop, or several of them, all quite meaningless, between the words of a sentence. Occasionally there is a capital letter where none is required. Rarely is the letter dotted, at any rate, many are without the dot, and the letter h at the end of words is generally written as many of us write, and as he himself often wrote, the finally.

The writing is very different from the readable hand which he wrote in 1833, when he was twenty-one, of which Ferrey (p. 76) gives an example with a beautiful uncial at the beginning. Later, in the ’forties the Earl of Shrewsbury complained of the illegible character of some of Pugin’s letters. Pugin replied: “I am very sorry for my bad writing, hut really, I have so many letters to write, so much work to do, and get so driven up for time, that my ideas go so much faster than the pen. I fear I cut the syllables short, but I will be more careful in future” (Ferrey, p. 125).

At first sight, then, the Winwick Letters are certainly not easy to decipher, but, when one gets used to the writing, there is a great fascination about it, and it seems to tell much of the character of the writer. Scarcely a letter is dated by Pugin, though he generally gives the day of the week, or the name of a festival. One of the few dated letters was written from Bolton Grange “April 18 (1849), but according to the weather somewhere in February”! [86], But the dates have in most cases been added by the Rector in pencil. A small cross is always placed before the address at the head of the letter, and another before the signature (of Life and Letters of Ambrose Phillips de Lisle, vol. xi. p. 215, note’).

The letters give us much information about the re-building of Winwick Chancel; about the intercourse between the great architect and his employer; about Pugin’s methods and his character, which, I think, is peculiarly valuable. They ought to be more readily accessible to antiquaries, and to others who are interested in the Gothic revival. All that I can do in the short limits of this paper is to give as many extracts from the letters as possible, grouping them, for the most part, around certain headings or subjects.

They were always most courteous in their correspondence and seem to have had a hearty liking for each other. They were constantly inquiring after one another’s health and considering one another’s feelings. The Rector had the strongest belief in his architect’s ability, though he never forgot his architect’s faith. He required that he should be made acquainted beforehand with every detail [42], especially every decorative detail, of the work, and sometimes he put his foot down very firmly. Quite early in the work a question arose between them. I will quote the greater part of several consecutive letters, which will tell the story in the original words.

In a letter without date [7] Pugin wrote: “I hope as there is a chancel screen you will not place a fixed railing round the Communion Table – it will spoil the whole east end of the chancel. I am sure we can arrange something better.”

Upon receiving this the Rector wrote as follows: –

—// letter start //—

MY DEAR SIR,

I exceedingly regret the state of your health. No man more sincerely than I – for your sake, for my own, and for the sake of Art in England – wishes you perfect and speedy recovery. Till it please God effectually to restore you, you will, I trust, pay that attention to yourself which your serious illness imperatively demands.

Your letter is most kind, and most considerate of my wishes. Believe me, I appreciate it as it well deserves.

It only remains that I state to you my confirmed sentiments on a point which I have already mentioned. And to a man of your good sense, candour, and honesty, I speak my whole mind, unreservedly, without fear or pain.

You are aware of my resolution not to shock in any degree, if possible, even the prejudices of my congregation, by any supposed approach towards the arrangements of the Church of Rome.

This resolve is strengthened by certain expressions in a work of yours1 to the effect that “it is impossible of the Anglican Church; and, further, “that if the present revival of Catholic antiquity is suffered to proceed much farther, it will be seen that either the Common Prayer or the ancient models must be abandoned.”

—// letter end //—

Pugin’s Essay in the Dublin Review, February 1842: –

—// letter start //—

The Present State of Ecclesiastical Architecture in England. “Deep and reverent chancels are utterly opposed to the principles and rubrics of the present Establishment” (p. 161, note). “It is as utterly impossible to square a Catholic building with the present rites”

Now, in any such possible alternative there is no question as to which part I shall cleave. My chancel must be strictly Anglo-Catholic. And I will willingly lose something of antiquity [rather] than give up anything of the identity of my own church.

This indisposes me to some things to which, heretofore, I had consented and makes me retain more stiffly what 1 contended for before.

My Communion Table must have a rail. I am unwilling to elevate the chancel so much as by four steps above the nave, or to have a step at the west end of the sedilia, and another at the platform of the Communion Table.

I incline to enclosing the Table as at present. And I very much desire to build the chancel on its existing elevation, removing only the accumulated earth. A bell I will certainly not put up, though I think I shall retain the Sanctus bell turret.

I desire the screen; but if, as I think you say, a screen and a Communion rail are incompatible, I will sacrifice the screen.

Now, my dear sir, I have honestly told you my whole mind. Every liberty which I claim for myself, I as freely allow to others. Therefore, shrink not from telling me yours.

And understand at once that if I exact anything which, as an architect or as a Christian, is irksome to your taste, or hurts your feelings, I think not for a moment of binding you to the work on which you have engaged, much as I shall grieve in dissolving our connexion, and sensible as I am that I cannot adequately fill your place.

square a Catholic building with the present rites as to mingle oil and water. It is most delightful to see the feeling reviving in the Anglican Church for the sanctity and depth of chancels, and, as a preliminary step to better things, it should receive all possible encouragement.”

—// letter end //—

Then follow the words quoted by the Rector: –

—// letter start //—

“If we part, we will part friends. But I confidently hope we shall work on, and through the piece, with increasing respect and affection.”

I am, my dear sir, sincerely and cordially yours,

JAMES J. HORNBY.

—// letter end //—

Pugin was scarcely used to this sort of treatment. Ferrey gives various instances of his off-hand way of dealing with his clients; as, for instance, his letter to his friend Lord Shrewsbury about the alterations to the dining hall at Alton:-

“If I am not enabled to exercise my judgment, and make use of my knowledge and experience, I am reduced to the condition of a mere drawing clerk, to work out what I am ordered, and this I cannot bear; and, so far from knocking under, I really must decline undertaking the alteration, unless your lordship will consent to its being made worthy of your dignity and residence . . . these architectural books are as bad as the Scriptures in the hands of the Protestants. I am very unhappy about it; and as regards the hall, I have nailed my colours to the mast – a bay-window, high open roof, lantern, two good fireplaces, a great sideboard, screen, minstrel gallery – all or none. I will not sell myself to do a wretched thing” (Ferrey, p. 119).

But Pugin’s reply to the Rector’s letter is as mild as milk. He wrote by return of post from London on his way home to Ramsgate:-

—// letter start //—

REV. AND DEAR SIR,

I have just received your letter on my way home and hasten to reply.

You must remember that I am both an author and architect. In the former capacity I enunciate certain principles, and write for the world. In the latter I act for my individual employer. And although I would never compromise essential points of architectural arrangement, yet I have never intruded my views in an unnecessary manner, and I have been particularly careful in the decorations of your chancel, and in the selection of subjects for the stained windows, not to introduce anything that would give the least reasonable grounds for offence.

We certainly hold enough in common to make a very magnificent chancel without introducing anything that you might hold objectionable, on the one hand, or departing from the old ecclesiastical arrangements of seats, &c., on the other.

Now, as regards the detail of this matter: –

(1) The chancel was elevated on account of the rise of the ground, and not for effect. If you build on the present level there will be [?], but the building will be miserably buried. Of course it can be done. I think it is a pity, but it is not a point to hold out upon, and if you can reduce the external level of the ground in the vicinity of the chancel, / will give up.

(2) The step on which the sedilia [?] is a more serious matter. I cannot conceive why you can possibly object to this. It is found in two-thirds of the English churches, and if it is done away, the end of the chancel will look flat and poor. I think, moreover, it will be severely criticised by all persons of knowledge and taste. If this step is to go, I can only give up under a protest regarding this measure.

(3) I have no objection whatever to your enclosing the Communion Table with rails, which of course would be carved in character with the Table itself, but I must remark that this sort of enclosure is a pure Roman, or rather Italian, invention. It began in Italy, where all the altars are so enclosed, thence into Spain, and France, and into England about the time of Charles I. I believe it to be a piece of Continental bad taste of the later times, but I will put up the rails, if you wish it.

(4) I implore and intreat of you not to do away with the screen. It is one of the finest features of the building.

In conclusion, I have only to remark that if on reflection you may feel that by employing an architect of my known principles, and so strenuous an advocate in writing of the old times, you would lay yourself open to attack or misrepresentation, I am willing to resign the work, much as I should delight in carrying out so fine a restoration. I leave the whole matter in your disposal and pray act in any way that may seem best in your judgment.

I remain, dear sir, with respect, your devoted servant,

Augustus Welby Pugin.

—// letter end //—

Then comes a letter from the Rector [13].

—// letter start //—

My Dear Sir,

Our diplomacy runs a smooth course and will have a happy issue. We have only to explain, and there is, then, little on either side to concede. Let me state the present position of my thoughts seriatim: –

If I cannot so far remove the circum-adjacent earth as to let the chancel stand with several feet of surrounding level, I will build on the higher foundation, as you advise. But for several reasons, which I will orally explain, I prefer maintaining the existing level.

Your concession of the Communion railing entirely removes my objection to the step west of the sedilia… I am as anxious as you can be to keep the screen. But I understood you to say that a screen and a Communion rail were, together, incompatible.

And, in conclusion, I have only to say that though I conceded to you the right of withdrawing, if my requisitions were inconsistent with your architectural principles or feelings, no such notion ever entered my head as that of backing out of my connexion with you on account of any suspicion that might, in certain quarters, attach to your name. My business is to see that nothing really objectionable even to sensitive prejudices shall creep in: having done this, I am quite indifferent to the possibility of ignorant or malicious misrepresentation.

I am quite conscious that the perfection of my work depends on its being in your hands; and anything to the advancement of Catholic principle.

Those who employ me must build in accordance with traditions of Christian architecture.” have sufficient proof that I cannot have a more agreeable, as well as efficient, person to deal with.

I wish you had named your health, and I earnestly beg you always to do so, till it shall please God to restore you to your accustomed soundness and strength.

I am, my dear sir, sincerely and cordially yours, JAMES J. HORNBY.

—// letter end //—

About a year later Pugin sent the Rector a sketch of the Communion rails, “which are simple, but I am sure you will be pleased with them in execution. They are now in hand” [56, Jan. 17, 1848].

On Feb. 23, 1848 [58], he writes, “There cannot be a doubt which is the best of your three propositions respecting the Communion rails – not a permanent railing, but one placed for the occasion. This would be capital, and the chancel will look twice as well. The rails are made, but they can very easily be adapted to this purpose and contrived to lift away. I shall be delighted. I assure you these railings are Roman, or rather modern Italian.”

So the rails were made movable, though, in practice, they are never moved, and they cost £62.

Regarding the level of the chancel, Pugin writes further [17, Mar. 12, 1847]: “As regards the level, if you could clear away the accumulated soil, I should not be so anxious for the increased elevation, but I feel certain you cannot remove enough to give the chancel its full external elevation. I am sure you will be satisfied with the effect as it is now arranged. I have directed the floor of the present chancel not to be disturbed on account of the graves, but the tile floor to be raised over it.” He desired to preserve all the graves in the chancel inviolate [29].

On Aug. 21 Pugin writes [36]:

“If I can improve a work during its progress, I am always anxious to do so, but I do not venture to introduce anything into the decorations of the chancel which has not your entire approbation.”

Again [44], “I will first prepare designs i.e. for the side windows] to the scale of 1 inch to a foot, coloured, and showing distinctly what is intended, which I will forward for your approval. I must intreat of you to let me place the mortuary inscriptions on the plates of brass (as they ought to be), and to have them affixed to the wall or let into the floor. The plates shall be supplied to you without any additional cost, only pray consent to let these fine subjects occupy the whole window. I am very anxious about this. I am always glad to see your handwriting, and you know the great interest I take in this work, which is the first chancel that has been properly carried out.”

On Dec. 19, 1847, Pugin sends some designs, and writes, “I think I have fully carried out your views, but in your letter you speak of the secondary subjects being treated in the background. This will not do; they must be introduced in quatrefoils above and below the principal figures.”

The Rector apparently objected to the oak-work being stained. Pugin, unlike modern architects, was bent upon having it stained. He returns to the subject again and again with great persistency:

[56, Jan. 17, 1848] “When all is finished, as I trust you will have a little gilding, the painters will give a beautiful tint to the oak-work. It will never look well unless this be done, and I know of a mixture that will answer perfectly and bring out the carving. Remember the carving and oak will not produce half its effect till it [is] brought to a fine brown colour. Respecting the oak, you may be assured that however well it may look at present, the effect will be doubled by being brought to a deep colour, which alone can bring out the effect of the carving. The ceiling will be wonderfully improved by a little gilding and decoration.”

In another note [82]: – “I am very anxious to see the oak work brought to a proper colour and the ceiling finished. Then the chancel will come out and will look old and toned down.”

Once more [83], writing some fifteen months after his first mention of the subject, the letter being dated “Wednesday in Passion Week, 1849,” he states: – “I hope we shall be able to settle everything without a wrangle. Indeed, I cannot imagine you a wrangler except you were at college, and I have no doubt of being able to bring you to consent to the true thing. I promise you that I will not spoil the work but bring out all its beauties. I am sure you will be satisfied with what I must propose. I will keep clear of a Friday this time, especially so soon after Lent.”

Eventually Pugin got his own way. The ceiling was gilded and painted at a cost of £120; a further £15, 10 shillings. was paid for the staining of the oak-work.

On Aug. 11, 1848 [74], Pugin wrote at the beginning of a business letter, “By the enclosed card you will perceive that I am married, and have got a first-rate Gothic woman at last, who perfectly understands and delights inspires, chancels, screens, stained windows, brasses, vestments, &c.”

Again [75, Oct. 17, 1848], “I am sorry to hear that your health is not so much improved as I hoped, but I trust the sight of the chancel will do you some good.”

Again [76, Oct. 28, 1848], “I had no idea that cushions would be used on the chancel seats. Certainly, the old men would have been quite satisfied with good oak. Hassocks to kneel upon are quite the right thing; I mean hassocks made of rushes, which I believe are even of Saxon antiquity… I rejoice to hear that you purpose visiting the church in a few days, which is certain proof that you feel much better. I assure you, if 1 were not so much occupied just at this time, I would come down to have the pleasure of going over the building with you.”

Again [77, Nov. 1, 1848], to Mr. R. A. Hornby, “I am delighted to hear that Mr. Hornby intends officiating in the chancel, and hope and trust he will not suffer any relapse from so doing. Pray give my best respects to him.”

Finally [81, Nov. 11, 1848]: –

—// letter start //—

“On my return home yesterday I found your kind letter, which I hasten to acknowledge. I am indeed truly gratified and delighted at the satisfaction you express on the completion of the chancel. The number of those who can appreciate good things is nearly as limited as that of those who can produce them, and therefore it is a real pleasure to work for one like yourself, who understands what is right. You know I am a sincere man, and am not given to flattery, and therefore you may believe me when I say that, if all employers were like you, the exercise of the architectural craft would be the most delightful pursuit possible.

I have inked in the sketch I made of the chancel, and enclose it with respects to Mrs. Hornby, as she saw it made and might like to possess a small view of your [N.B. sic] work.

I am always hard pressed for time, or I would have made a larger drawing for her. And now let me again thank you for all your kindness, and for the opportunity you have afforded me of re-producing an old chancel; and, hoping to see you before long in increased health and strength, – Believe me, with great respect, your devoted servant,

A. WELBY PUGIN.

—// letter end //—

THE CONSERVATIVE CHARACTER OF THE WORK

Sir Stephen Glynne began his survey of the Lancashire churches in 1833 and ended it in 1873.

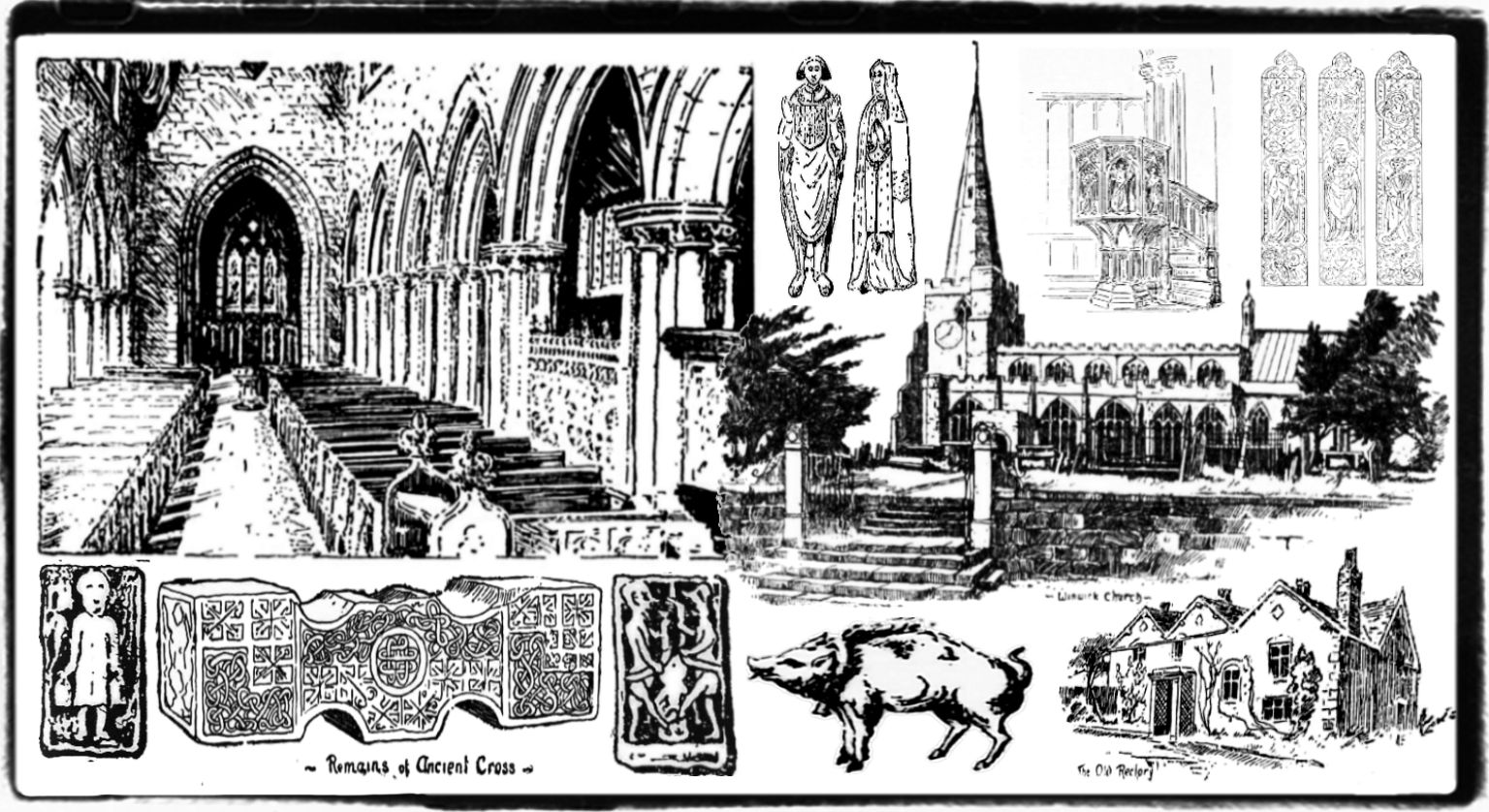

He visited Winwick Church probably before 1836, in which year there was a considerable amount of rebuilding, which he does not mention. He speaks of the then existing chancel, which he says is “by far the finest part of the church, and presents an excellent specimen of Decorated work, though the windows have lost their tracery, and the badness of the stone has caused the decay of the external ornaments. The east end has a high gable, and the buttresses have triangular set-offs” (Notes on the Churches of Lancashire, Chetham Society, N.S., vol. 27).

He had a good deal more to say about it, for which I have here no space, but especially he mentions the “very elegant mouldings,” the “rosettes alternately round and square” in them (i.e. the “ball flowers,” and the “four-leaved flowers ”), and the “sedilia,1 a piscina, and a door, all forming part of one plan.”, If we look at Pugin’s work at Winwick with this description of the earlier work in our mind, we shall be quite inclined to believe that the restoration or re-building was a very conservative one.

The letters make it abundantly clear that it was intended to be so. In one respect it was not so. In Baines’s view of the church in 1836, the apex of the chancel roof reaches only to the battlemented parapet at the east end of the nave. Pugin raised the walls of the chancel, and consequently the roof ridge is considerably higher than that of the nave; and although the difference is to a certain extent minimised by the insertion of the Sanctus bellcote, the raising of the line of the chancel roof externally is certainly unfortunate.

Within, the increased height gives the chancel great dignity. Why Pugin raised the roof, as we have already seen, was to avoid disturbing the remains of the dead, and yet to keep the due external proportions of the chancel.

In every other respect he seems to have been thoroughly conservative. [2] “Respecting the side windows, when Mr. Myers goes down he will make templates of the remains of the tracery, and then I will set out the windows with two lights and three lights, and you will see the difference, and we will then decide. Respecting the east window, I am quite willing to keep it as it is, if you prefer it. As a principle I would rather restore than alter in old buildings.

Of course there are exceptions to this rule. I fear that if I shorten the east window,2 the brilliant effect of the east end will be diminished: –

- On Mar. 12, 1847 [17], Pugin asks, “Will you have the old sedilia carried down to the Hall to be set up in the grounds?”

- Pugin had thought of doing this to get a better reredos. Cf. True Principles, p. 50, “An old English Parish Church… with the brilliant eastern window terminating the long perspective.” we will do nothing hasty or that we shall repent of afterwards. I am anxious to make this a very perfect work.”

[5, Nov. 4] “After very mature consideration I am now quite opposed to any alteration of the original window. If we restore it exactly, no one can find fault, and I think it will be more satisfactory in every way. Moreover, I can get a very good sort of reredos under the window, of which I send you a sketch. If I carry a set of richly moulded panels with vine leaves all-round the sides and over the table the effect will be very good, and I have seen old examples of low spaces under windows treated in this manner.”

(cf. ancient reredos in Oldham Chantry, Exeter Cathedral). [21] “The new stone should be worked as nearly as possible to the old.”

Also he noted [40] “The moment I return to London I will hunt the mould up, but I fully believe and expect it is exactly like the original, for I have kept closely to the old mouldings without alteration.”

Later Pugin added this into another letter, [89, Dec. 5, 1849]: – “I can assure you that I never took greater pains with any work than this. Every detail, every ornament, was arranged with the greatest care.. I do not hesitate to say it [is the] best restoration that has hitherto been accomplished.”

THE STONE

The Rector had a quarry near the church, from which came the stone originally used. At first Pugin wished to use this stone [9, Jan. 6, 1847] “which I believe, if properly bedded in the building, to be excellent. I wish I had your quarry near my church” {i.e. at Ramsgate). [10, Jan. 20, 1847]

“If the case was mine, I should certainly employ the material from your quarry, which I think quite as good as any stone in the neighbourhood, and a very fair stone in itself… I do not like the idea of making the tracery of one material, and the jambs, &c., of another. I am sure this will not have a good effect.

Nothing will look as well and harmonise with the old church as your own stone. Remember the present chancel has been standing for about five hundred years, and I do not think the old men took the best quality of the stone, and at the end of five centuries all stone will look rather the worse for standing. My own opinion is decidedly to employ your own stone in this erection, but in an affair of so much importance I do not wish to act against your own wishes, and therefore I am quite prepared to estimate for any harder material you may propose.

Mr. Myers [the builder] is well acquainted with every description of stone, no one better; he has long experience of all their qualities, and I have great faith in him in these matters. Pray talk the whole case over with him.”

The Rector agreed to the use of the Winwick stone [11].

[17, Mar. 12, 1847] But three months later Pugin changed his mind. “I have been an hour at the quarry. Some of the stone is very good, some exceedingly bad. All that is not sound we have condemned, and Mr. Myers has agreed to get stone from Stourton Hill, which is the same colour as the best of the Winwick, for the tracery and some of the parts most exposed to weather.

This will not be attended with any increase of expense – he is anxious as myself to make a fine work.”

It was finally agreed [24] that all the stone should be from the Stourton Hill quarry, Cheshire, and again Pugin wrote [18], “I am exceedingly rejoiced at the arrangement respecting the stone, for the quarry at Winwick was so unequal, that at least two-thirds of the stone got was unfit for the intended purpose. I shall now be perfectly satisfied and easy.”

[20, Mar. 17, 1847] Myers writes to the Rector about the Stourton stone, and the final sentence of his letter is, “I never met so [sic] Mr. Pugin so particular in my life to make a fine job.”

THE STAINED GLASS

All the windows of the chancel were filled with stained glass. Pugin originally proposed to put into the east window [2] the “ four greater Prophets under the four Evangelists – then we shall have the Old and New Testament.” But later on [36, Aug. 21, 1847] he wrote: “I am anxious to make an alteration in the east window of your chancel, for reasons which I will endeavour to explain. I find from a very learned treatise on the porches of Amiens and other authorities that all representations of prophets and personages of the Old Testament typical of the New should be confined to the western portions of churches, and chancels should be decorated with personages and subjects exclusively from the New Testament. This appears to me most beautiful in principle – particularly applicable to an east window.

- I am proceeding with the Evangelists and have now the assistance of Overbeck’s best pupil, who has arrived in England, recommended to me by Overbeck himself. I have also some very splendid Authorities for the other saints, which I got in my last journey.

- and if you will allow me to introduce them, we shall have a very glorious window.”

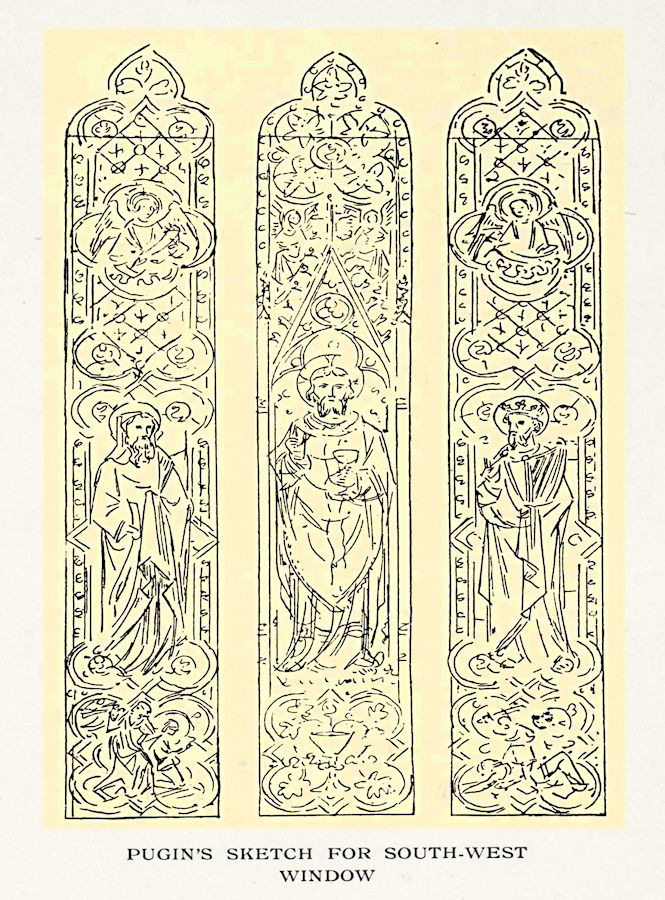

PUGIN’S SKETCH FOR SOUTH-WEST WINDOW

Again, he wrote [47, Nov. 11, 1847]: “Your east window pleases me, and therefore I am sure you will be satisfied, for I am much more difficult to please than you are – the Evangelists are coming out gloriously.”

But later on it was discovered that, through a mismeasurement, the glass had been made too long for the stonework, and Pugin writes [70a, May 26, 1848] : “The window will fortunately not be spoiled, but we shall lose the emblems of the Evangelists, which is a great pity. I never took so many pains with a window in my life… You must find some place for the emblems of the Evangelists in another window of the church. They are too fine to be lost.”

Again [71, June 7, 1848]: “I have arranged the alteration in the glass. I do not think it will be perceived, but the general beauty of the window is certainly much diminished.”

It was originally intended to fill the side windows with “borders, arms, and emblems.” But [42, Nov. 10, 1847] the Rector suggested “a more ambitious scheme, which I do subject to your better taste and my pecuniary ability.” His proposal, suggested, he says, by his son, Mr. R. A. Hornby, was “that the three windows of three lights should be devoted to religious illustration [i.e. instead of arms, &c.J, and that each should represent our Blessed Lord in some particular aspect towards His Church.”

Pugin replies by return of post [44] : “I am quite delighted with your son’s suggestion about the side windows, which will be indeed a great improvement. As regards the additional cost, it will be principally incurred in the preparation of the cartoons, which must be first-rate, and do

the finest design, in Italy. I never saw any stained glass so beautiful as that at Perugia.” Copied also to a Letter to Lord Shrewsbury of the same date (Ferrey, p. 126).

justice to the majesty of the subjects; but for ^29 a window, f8y extra for the three windows, I would undertake to get them perfectly executed.” About a month later [48, Dec. 19, 1847] he sent designs for the side windows, and several letters passed. [52, Dec. 26, 1847]

South-west window: “You stated you wished Our Lord represented in this window as a priest, and therefore I introduced the chalice as the most appropriate emblem.”

South-east window: “The subject of the prophet in the fiery car is from a very fine old example… The hand, with a nimbus issuing from a cloud, denotes the Presence of God, and refers to a voice saying, ‘This is My Beloved Son, in Whom I am well pleased.’ Pray do not alter this, for it is a fine old traditional way of treating the subject.” [71] “I cannot agree with you about the bars. A few lines cutting the window does good rather than harm.”

So, the windows were fixed and approved of, and he writes to Mr. R. A. Hornby [72, June 10, 1848]: “I need not say how delighted I am at your favourable opinion of the windows.” They were executed by Messrs. Hardman & Co. of Birmingham, with whose firm Pugin was commercially connected {Penny Cyclop., 2nd Supp., 1858); and it is interesting to read in Sir G. G. Scott’s Recollections (p. 218) his opinion in 1864, in speaking of glass-painting: “Hardman, or rather his artist Powell [Pugin’s son-in-law and only pupil], has had the advantage or disadvantage of a long drilling under Pugin. It made him a first-rate glass painter, but on the death of his great master, instead of turning to old examples, he has been content to work on upon the material bequeathed to him, which has become from year to year more diluted… The works he did for Pugin have been as yet barely surpassed, e.g. those in the Houses of Parliament.”

TILED FLOORS

Regarding the supply of encaustic tiling Sir G. G. Scott writes (loc. cit.): “We have made little progress since Pugin’s time. No one has equalled him in the designing of patterns, though I think that Lord Alwyn Compton greatly excels him in arrangement.”

Pugin had quite as good an opinion of himself in the matter of tiles. Quite early in their correspondence he wrote to Rector Hornby [7]: “You ought to have some faith in me, for I have always been considered a first-rate man for floors. The Bishop of Bath and Wells [Bagot] says that the only modern tiles that please him entirely are those I laid down in his chancel at Leigh Church. You will, I am sure, be satisfied with the design for the floor, when I show it to you drawn out to a large scale and coloured.”

On the same subject he writes from Florence [29, May 17, 1847]: “I have also a great collection of examples of antient tiles, composed entirely of diapers and foliated work, and, as you are so much opposed to heraldry, I suppose I must confine myself to these, but I quite grieve at not having some of your horns; at least they would have been so appropriate, and would have relieved the other patterns.”

He insisted on using glazed tiles. [62] “At Newcastle, I am actually taking up unglazed tiles to lay down glazed ones in their place.” The glazing is by this time much worn off.

MISTAKES

These were sometimes made, and they drew from Pugin letters which show at once the impetuosity and generosity and truthfulness of his nature. We notice the same readiness to admit a fault, which led him to write in the concluding words of his True Principles (p. 67): “Christian verity compels me to acknowledge that there are hardly any defects which I have pointed out to you… which could not with propriety be illustrated by my own productions at some period of my professional career.” (Cf. Revival, p. 15, note: “but a few years ago I perpetrated abominations.”)

As we have already seen, an error was made regarding the length of some of the lights of the east window, and Pugin writes [70a]: “You may well say this glass will make me desperate, but the error is Mr. Myers’.”

But twelve days later, having made further inquiries, he wrote [71]: “I have been absent from home on this unhappy business… it is difficult to say with whom the error originated.”

Again there was a mistake in the inscription on a brass plate, and Pugin wrote [77]: “I am wild and furious about the plate… if it is the engraver’s fault, it must be rectified at his expense. I am dreadfully annoyed about it, for I took the greatest pains to have it right.”

Then later [78]: “I am truly sorry for the omission, but I am not quite sure if it is an error of mine or not.”

And later still [80]: “If there is any error in the inscriptions, I fear it is my fault. That in which one of your names was omitted was certainly a mistake of mine, for Hardman sent me the inscription written out by myself. So, you must not blame the poor man for my faults.”

After the whole work was completed in November 1849 there was some slight settlement or defect, of which a good deal was made by a Mr. Thomas Stone, apparently one of the churchwardens.

Pugin made a careful inspection, and then he wrote [89, Dec. 5, 1849]:

—// letter start //—

“I think both the arch and drain were neglected by Piddock [Clerk of Works], for which I blame him very severely…

It shows a very bad feeling on the part of any churchwarden to make such a formal business of a matter consisting of a coalhole arch and a top drain, that could be perfectly rectified for a few shillings…

I assure you your letter caused me the greatest uneasiness… in the meantime a report is spread that the building is falling, and it would not surprise me if it got improved by repetition till the whole church was supposed to be in ruins, and you or me, or perhaps both of us, buried beneath them!

But seriously, I trust you will remove, as far as lies in your power, such injurious impressions. I believe the chancel will last longer than its predecessor.”

—// letter end //—

Then three days later [90, Dec. 8, 1849]: “Since I wrote to you I have had Myers down here, and he assured me… I am glad of this, because, as far as the drain [?] it exculpates Piddock.”

Pugin had a little trouble of his own with an architect at Ramsgate, to which he refers [89, Dec. 5, 1849]:

“I find the owner of the adjoining land to mine is known to you, Mr. Habersham. I don’t know what he may be as an architect, but I am a fool to him at a bargain. The modern fellows beat the Gothic men at a deal.”

[90, Dec. 8, 1849] “I had no intention of making any charge against Mr. Habersham. I merely meant, what is quite true, that I could not deal with him. As far as any negotiation with that gentleman goes, I have given it up in disgust and mean to protect myself against his Cockney row of houses by the best means in my power… I think I have found an excellent plan.”

[91, Dec. 10, 1849] “You will be pleased to hear that there is every prospect of matters being amicably arranged between myself and Mr. Habersham… I can assure you I have every wish to act towards him in the friendliest manner, but the prospect of a gable end a few feet off my east window made me almost frantic, particularly as I had been cheated out of the land by the parties who sold it to Mr. Habersham.”

THOROUGHNESS

Again and again in the letters one meets with evidence of Pugin’s painstaking care and diligence. “All those who knew Pugin will recognise at once that his chief characteristic was thoroughness” (Mr. E. S. Purcell, qu. Ferrey, p. 461).

Soon after the beginning of the work he had a severe illness, often referred to in the early letters, which completely disabled him for a time. Ferrey mentions it (p. 194).

Pugin himself attributed it in great measure to the worry caused by his love affairs.

At this time, he was full of work. He had a large private practice, chiefly amongst Roman Catholics. Most, if not all, of the details of the new Houses of Parliament were from his hand (cf. Ferrey, p. 256). He employed no clerk. “Clerk, my dear sir! Clerk! I never employ one. I should kill him in a week” (Ferrey, p. 187). He did a considerable of work and correspondence.

In one letter he wrote [2, undated] “I have been so very ill since I was with you that I have not been able to write. This is the first severe illness I have had in my life, and it has pulled me down so much that I can hardly sit up.”

[4, Nov. 5, 1846] “I am better now and able to work.”

[7, undated] “I am still very ill, unable to leave home or even the house. I went to London for a consultation last Wednesday, and they give me no hope of speedy improvement. However, I can draw and design, and therefore I must not complain.”

[17, Mar. 12, 1847] “My health has been so very uncertain, and although I am able to attend to business in some measure, I am by no means in a state of security.” amount of literary work also. And yet, if he had been only a beginner on his first work, he could not have given it more attention than he did to Winwick. Except for the heating apparatus, which he frankly owned [1] that he did not understand, everything came under his hand.

Pugin was indeed what he delighted to call himself, the “master of the work.” He made sketches, and drew the plans, using, so we are told, only a compass, a two-foot rule, and a stump of a pencil (Diet. Nat. Biog.).

And as Myers said [15], “Mr. Pugin always makes them [i.e. his plans] out to a small scale… and I enlarge them to the full size; he has full confidence in my capabilities as to this work, as I do it in every church I build for him; in fact there is but little to do, as he gives them so very clear and plain that they only want enlarging.”

Pugin [18] speaks of making working drawings, and of [17] “modelling the bosses for the ceiling.”

All the finer detail work was done under his own eye in London. [41] “I am now at home working away at my details.”

Pugin was responsible for every detail in the stained glass. The Noah’s Ark in the north window may be mentioned as a particularly delightful detail, with its five windows, out of which look Noah, a lion, a stag, an eagle, and a swan, the rain coming down like rods out of amethyst clouds into a wave covered sea.

He even found time to design a sanctuary carpet [45] to be used “on Sundays and great feasts and to be removed at other times.” This was worked by some fourteen ladies in strips or squares, and Pugin writes when he sends the pattern, full-sized and coloured [46]: “I hope you will follow the pattern exactly, for I have taken great pains with the design, and it will harmonise perfectly with the rest of the work.”

Pugin speaks again and again in his letters of his interest in the work, and of the pains he has taken. And he has supreme faith in himself.

There is a confident ring in all that he writes. In his first letter [1] he says: “I also forward two perspective sketches which will give you an idea of the interior effect, which I think will be very solemn – few chances indeed, would be superior. I have gone carefully into the estimate, and the amount I now send you is dependable to a shilling.

The confident egoistic note recurs again and again in letters I have already given. But we must remember that Pugin was famous early and was now at the summit of his fame. Moreover, the finished work excuses and justifies the egoism.

The Winwick Chancel is indeed a masterpiece, solemn, dignified, satisfying. It was opened, without reconsecration near the end of 1848.

The Rector preached the first sermon, which is preserved in the Winwick book. The inscription, dated Dec. 2nd, 1848, is to his neighbours and dear friends “by one who, in duly ornamenting God’s House, desires to build up the Spiritual Church committed to his charge, after the pattern of things in the heavens.”

Within the chancel, on a brass plate, are these words: “This Chancel, impaired by time and injured in the Great Rebellion, was rebuilt on its old foundation and restored to its original form, in more than its original beauty, in the years of Our Lord MDCCCXLVII and MDCCCXLVIII. James J. Hornby, Rector. A. Welby Pugin, Master of the Work. George Myers, Builder. Laus Deo.”

In an extract from a letter [39, Oct. 8, 1847] of Dr J. B. Sumner, then Bishop of Chester, afterwards Archbishop of Canterbury: “I have consulted with the Chancellor about the consecration of which mention was made on Monday, and we find that ecclesiastical law and usage do not justify the consecration of a portion of the church, even though completely renewed, as from time to time has been the case with the aisles, or nave, or towers, or chancels of our cathedrals. The church still retains its identity.”