Saturday 23 December 1882

The enthusiasm which the new Ship Canal has evoked in commercial circles, having extended to Newton, naturally caused the mind to turn for a time to the “Sankey Canal” by way of antithesis. Not that this was the first canal made in England by any means, for the Romans, during their residence in England, cut a canal from the vicinity of their metropolis, the city of York, as appears from Drake’s Eboracum. In the year 1121, Henry I made a navigable canal of seven miles in length from the Trent at Torksing to Witham in Lincoln (see Sim. Dun., cap. 243, and the chart of Richard of Cirencester).

The Sankey Canal did not, therefore, give rise to the first canal navigation made in England, but if qualified by the words “in modern times,” the expression would be correct. An undertaking commenced in 1755, under the general powers of an Act for making navigable a river, in reality gave rise to the first canal navigation made in England. It runs entirely separate from Sankey Brook, except for crossing and mixing with it in one place about two miles from Sankey Bridges. Its length from Fidler’s Ferry to the place where it separates into three branches is nine miles and a quarter. From there, it is carried to Penny Bridge and Gerard’s Bridge without going further; but from Boardman’s Bridge, it runs nearly to the limits of two thousand yards, making the whole distance from the Mersey eleven miles and three-quarters. This canal has proved very beneficial both to the public and the undertakers.

Some of the first collieries upon its banks are worked out, but others have been opened, notably the Havannah collieries. Its business increased by the plate glass manufactories and chemical works founded near it in the neighborhood of the populous town of St. Helens. Formerly, the large copper works belonging to the Anglesea Company, which, like Muspratt’s Chemical Works at Newton, had to be removed and discontinued. In passing the site of it, now occupied by the Sankey Paper Mill (now also at a standstill), we could not help thinking of the time when we saw the great chimney, 400 feet high, blown up by a company of “sappers and miners” from Liverpool. We could, in imagination, see it drop down like a huge “spill” collapsed, while thousands of people were at a respectable distance expecting it to fall endlong.

How odd it is to read in the first edition of Baines’ History of Lancashire about the state of public feeling in 1824: “A new mode of conveyance, more rapid, and it is said more economical than water carriage, has been instituted in some parts of this kingdom. In the year 1822, a project was formed for constructing a railway between Liverpool and Manchester, on which steam-impelled carriages should travel, both with merchandise and passengers, at the rate of ten miles an hour. A number of gentlemen in Manchester and Liverpool, persuaded of the practicability of this design, entered into a subscription to defray the expense of a survey, with a view to a parliamentary application, and the requisite sum of three hundred guineas was subscribed for the purpose. In the autumn of that year, William James, Esq., an engineer of London, executed the survey, and suggested a line of road from Manchester by way of Eccles, Chat Moss, New Church, Newton, Rainhill, Huyton, and West Derby to Liverpool, making a distance of 31 miles. Public notices were accordingly given of an intended application to Parliament, but the measure was not followed up owing to an apprehended opposition from the whole body of inland navigation proprietors throughout the kingdom, and from other causes. How long these causes will operate it is difficult to say, but if, as is asserted, the conveyance of goods between the two towns of Manchester and Liverpool can by means of a railway be effected at a little more than half the present charge for water carriage, and in one-fourth of the time, the resistance of any body of men, however powerful, to so great a public improvement will, in the end, prove as futile as was the resistance of the land carriers of the last age to the construction of canals.”

Taking advantage of the fine winter’s day, we set out for an invigorating walk along that portion of the canal which lies in the township of Newton, and within sight of Bradley, described by Leland nearly three hundred and fifty years ago as “Newton on a brooke, a poor market, whereof Mr. Langton hath the name of his barony. Sir Perse Lee, of Bradley, hath his place at Bradley (the moat and ancient gateway still remain), in a parke a ii. miles from Newton, and we learn that Edward the Confessor was Lord of Newton, the barony of which passed successively to Roger de Poictou and the Langtons, and the Legh family acquired the property by purchase about two hundred and fifty years ago—the fee of Mackerfield being of great extent, including parts of twenty-one townships, and our authority says ‘The sports of the turf and of the cock pit formerly prevailed in this borough to a considerable extent, but in the year 1816 they were discontinued, or rather suspended, for it is now (1824) announced that Newton races are to be resumed in 1825, and held this year, and in future years, the first week after Manchester races.'”

The next editor may add that in 1882, a new coursing ground was opened, which bids fair to take the place of the old rabbit running. For various reasons, the coursing was postponed the other week till a more convenient season, and we may piously hope (“Anglo-Scotus” will lift his hands in amazement at this) that the fortunate shareholders in the new concern may not be too much downcast by their lack of success so far. But as it is said, “too many cooks spoil the broth,” so too many of these coursing grounds diminish the chances of patronage to each. After all, Lord Sefton does not intend to give up Altcar, any more than Mr. Legh his twenty years’ contract, so the shareholders are evidently in for “a good thing”—whatever their ill-wishers may say.

Apropos of nothing in particular, we cannot resist the temptation to tell “Anglo-Scotus” through your columns that in the year 1824-5, the sum of £14 18s. was paid, in this Newton of ours, to the mole catcher! Almost everybody in Newton has heard of or seen Castle Hill, but comparatively few know of or have seen the tumulus, which is within a stone’s throw of the Red House at the bottom of Newton Common, and on the banks of the Sankey. As far as we can see by the ordnance survey map, it is the only one that is on the banks of this ancient river. Being on our way, we turned aside to see once more this ancient burying place, and from the canal bridge at the crossing to the Havannah Collieries had a good view of this “hillock upon a mountain,” as it would be called by a Celt. We wished for another “Old Mortality,” or at least an amateur photographer to preserve its outline for us, for we observe there is a trench of a yard or two in its south side today. It is some 21 yards by 31 yards of an irregular slope and about three yards high, having evidently been explored long before the Government survey of this part of the county was made in 1843. We opine that this surveying party was the means of drawing attention to Castle Hill, not then explored, but afterwards found to be a burial place. Some may have thought we were making merry with grave matters when we supposed the locality already dedicated to the repose of some ancient worthy, but so it is, and “white is the world,” to use the expressive phrase which in the Welsh language is usually carved on gravestones of the mighty dead. Literally so today, though in quite another sense than that meant, for the ground is covered with snow.

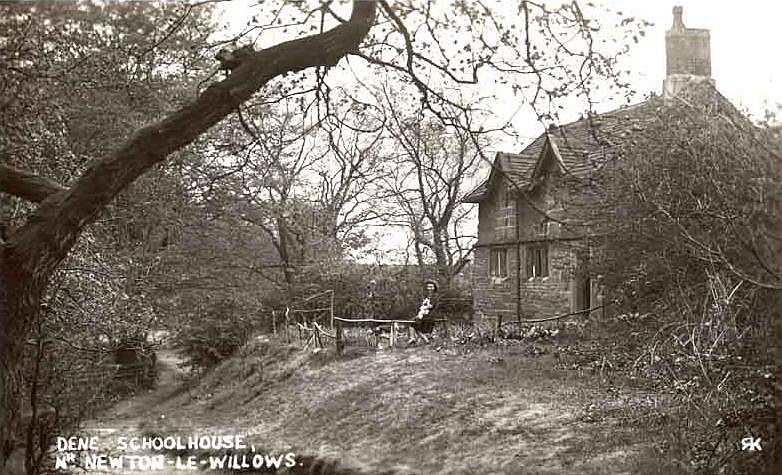

Making our way to Collins Green, where in passing the other day we saw that a new station was being built and a road driven under the line to do away with the level crossing, approaching through the fields, we notice the drainage works, which form part of the improvements. Soon after, we “forgather” with an intelligent stranger with whom we strike up a conversation anent these matters. Crossing the line, we find ourselves standing beside the barricade fencing off the new cutting, and remarking upon the different appearance of a finished and unfinished piece of work. We observe the greater knowledge and skill of civil engineers now than formerly, which makes them demand better work of contractors. We also discuss the really good work put into Earlestown bridge by Mr. Fisher, who is also the contractor for this new piece of work, which seems most satisfactory so far. A new house is to be built where the old station is. One of the signal boxes is to be done away with, along with the present road, and a grand new hotel is to be built near where the Pear Tree public-house is, with proportions that are to be something handsome, and the accommodation ample; the expense will be adequate to the means of Sir Gilbert Greenall—a sum we hesitate to mention out of deference to our friends of temperance. So far so good.

When the signalman sung out “Look out,” our new friend quietly said, “Your dog is done for,” for he was on the track, just at our heels. In an instant, we stretched out our hands and grasped him, stepping on to the track while doing so, when we

saw the Manchester express clearing the nine arches. In less time than it takes to tell, we were holding on to our hat to withstand the wind caused by the rush which the train brought up with it. Our friend looked a moment, and then said, “You nearly lost your life because of your love for your dog.” We thought, “That is another example of the dangers of a level crossing,” and it brought to mind the action of a relative of ours, who, seeing a man on the track of an express, flung herself at him, and threw him into the six-foot. That was esteemed an act of bravery, and so rewarded—this an act of folly. So differently are things regarded by some people.

Conversation turned on the state of the nine arches, which we thought, in passing under them, safe enough, and so they are with this slight defect: the foundations have shifted, and so the superstructure is slightly out of “plim,” an expressive phrase which means that, like a drunken man, it is just a little out of the perpendicular and may some fine day descend to the level of the Sankey, over which it proudly sits as a picturesque object in the landscape.

This is transcribed from the St. Helens Examiner – Saturday 23 December 1882