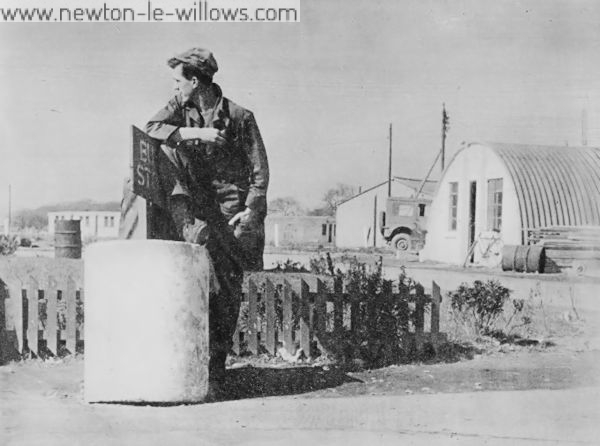

Four miles from Warrington in Lancashire, is Burtonwood, the great maintenance base for the American Air Lift to Berlin. There several thousand young Americans, most of whom had never been overseas before, were dumped far from their homes with orders to keep the Dakotas, Skymasters and other aircraft flying through the air door in the Iron Curtain. The success of the Air Lift was apparent to all, but locally the social consequences were less happy for both sides.

Six thousand American airmen dumped down suddenly to live near a bleak Lancashire town. Few have ever been overseas before. Fantastic stories are heard of their behaviour. Sensational reports appear in the Press. Public protests are made. There are bitter recriminations from both sides. Picture Post sends Edward Shackleton, M.P. for Preston, up to Warrington to make the first independent social survey of the situation.

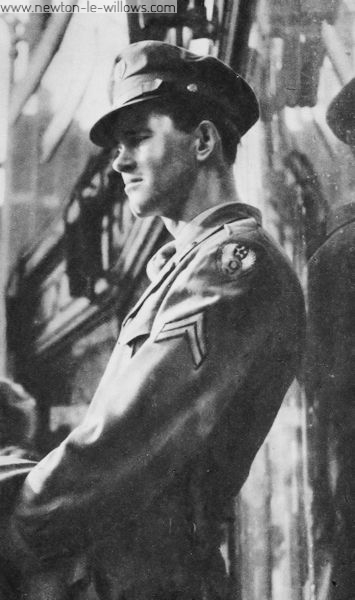

At Burtonwood the men live on dispersed sites spread over an area of several square miles.

The demands of the Air Lift had to come before the provision of social amenities, for the importance of Burtonwood in the Air Lift’s success cannot be over-estimated. As this began to get organised to its present clockwork precision, it was decided that every American aircraft should undergo its main inspection and maintenance work at this one centre, and special machinery and equipment has been, and still is being, installed to do the work which the extraordinary conditions demanded. The American authorities have, none the less, made strenuous efforts to improve the

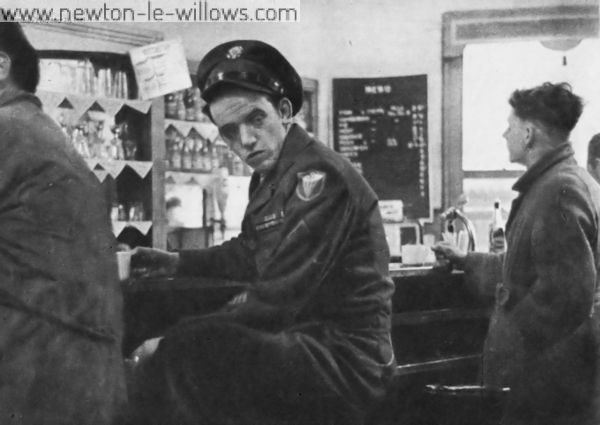

situation at Burtonwood: theatres, clubs, canteens and stores have been created out of the mud of the airfield. But the American soldier—like any other soldier in the world living in camp—has one main objective, and that is to get out of it, and this means a visit to the town of Warrington. It is the gateway to that different life to which every soldier is longing to escape.

Warrington is a bustling, energetic, prosperous Lancashire town. It has an unusual diversity of industry, since the inhabitants are concerned not only with the spinning and weaving of cotton, but the production of a wide variety of manufactured goods. Even at times of the great depression, it never suffered as much unemployment as the other Lancashire cotton towns. It is a fairly typical industrial town, warm-hearted and full of the vitality of the provincial North of England, and it possesses some good parks and a fine Georgian mansion for a Town Hall. None the less it hardly represents the day-dreams of the young Americans, and certainly it does not provide all the things which they want and can afford to buy. Even an American private has about five pounds a week to spend, and after his monthly pay-day he is pretty keen to spend it. He comes into town after the shops are closed, with a choice of the cinemas, the pubs and the dance halls. He is usually a friendly person and he wants to find someone to talk to. As psychologists would put it, he wants, like any other human being, to be loved. The American likes to be big-hearted and to be thought big-hearted. Most men, no doubt, want this, but the American wants it more simply and directly than other men. The American soldier wants a girl, not solely because she is female, but also because he wants to show his family photos to her.

There are also many differences in behaviour. American courting technique is different from the European. Because it is different, it is apt to appear shocking, especially in places with the strong social customs of an English town like Warrington. The Americans, too, are so accustomed to ‘folding money’ in the shape of dollars, that they are apt to treat pound notes in the same way and throw them around broadcast. Small differences in behaviour, even in clothing, strike an alien note, and tend to cause irritation among the local population.

The problem is to combine the two ways of life : to persuade people to see that, because an American is accustomed to drinking through a straw from a bottle of Coca-Cola, the absence of a straw will not make him ask for a glass—he will merely drink direct from the bottle ! It is from this sort of thing that mutual unfriendliness springs. Drunkenness always seems more offensive when the drunk is a foreigner, and some nights, especially after payday, there may be a number of drunk Americans in Warrington. Perhaps the fault here lies with the comparative smoothness of Scotch whisky, for people who are unaccustomed to it do not always appreciate its kick. At any rate, a mixture of motives and habits such as these have led to the so-called ‘scandals of Warrington.’The first hint of trouble came as a result of a fight in the town, and a word from the Bench started off the publicity. Three American airmen, walking through the town with their girls, were set upon by some rowdies, and a scuffle ensued. This was soon broken up by the police and no harm’ resulted. Unfortunately this was not the end of the evening. The Americans went on to the railway station where a ‘drunk’ suddenly attacked one of them and knocked him about very badly. Police enquiries led to the charging of the ‘drunk’ and, on conviction in the police court, one of the local J.P.s somewhat unnecessarily commented that the Americans had only themselves to blame. After that the sensational news-hounds were on the trail. Articles in the Sunday newspapers reported scenes of orgy and vice. An American paper reported that women were having to be driven off the camp with sticks. There was talk of trains coming in from all over the country loaded with prostitutes and young girls out for a good time. One Sunday paper published an article under the headline, “This Town Wants Cleaning Up,” while the Mayor’s secretary cracked back, “Warrington is no Klondyke.”

Police raids were made, and young girls appeared before the county magistrates on various charges. Anxious wives and mothers in America feared for the corruption of their menfolk, while the people of Warrington woke up to the fact that the name of their town was becoming a byword overnight. Some were unwilling to let their daughters go out in the evening, and it was even suggested that for a girl to be seen walking with an American soldier was tantamount to admitting that she was a ‘floozie.’ Certain pubs, for no particular reason, became the meeting- grounds for Americans and their girls, and the pub-keepers saw their regular clientele driven away. The age%)ld problem of the camp-follower was seen in its latest form.

How bad really was the situation ? Any journalist knows that the same facts can be made, to tell totally different stories, and, of course, the anti-Americans and the anti-British used the rumours for their own ends. In the event, as with any form of trouble with news value, the story became sensationalised out of all proportion.

The first fact is that it was never, at any time, out of hand. The Chief Constables of Warrington and the County Police had been at the game too long not to expect trouble, but they had the resources of long years of British police experience to enable them to deal with it. And they have dealt with it. It is perfectly true that young women and girls, some professional prostitutes, some children whose mothers didn’t know they were out, converged on Warrington. A number of girls came from as far as Middlesex, Leicester and Newcastle—lured by the prospects of a good time, the

money, the food, the chocolates and the nylons, which they believed the Americans had in plenty.

The police went into action. It is, of course, difficult in a free country like England to stop undesirables going anywhere they like, but the police, in full collaboration with the American authorities, set about it. Some raids on the camp itself led to the arrest of women, and their appearance before the county magistrates on the technical offence of being in possession of American bedding !. Police action in this case was deliberate, and publicity was sought to frighten the others, while the Americans dealt with their own men. Police, including policewomen, carried out constant identity-card checks. This quickly revealed to the police which girls came from out of town, and when no card was forthcoming, the home police were notified and the girl’s parents interviewed. In many cases the parents’ comments were, “Wait till I get there and I’ll deal with her.” Gradually, the police worked the thing out, so that today the stream has dropped to a trickle.

Though it is not reasonable to expect the total disappearance of the problem, especially since the neighbouring cities of Manchester and Liverpool are also to some extent involved, at least the good name of Warrington is safe.

What of the American end ? The opinion of most people in Warrington to whom I spoke is that the majority of these young Americans are decent and well-behaved. Certainly the damage to property they do is negligible—particularly in comparison with some of those major achievements in destruction which Allied and Dominion troops performed in this country during the war. The Clerk to the Justices, in fact, told me that the number of Americans in any way involved in cases leading to court action is under double figures. That seems modest enough. However, in any large body of men there is always a certain percentage of troublemakers.

One of the immediate needs of the situation, of course, was full co-operation between the civil and military authorities. Certainly on the police side this has been established. Both the American Provost Marshal and the Chief Constable of Warrington stress the excellent co-operation that exists. There is a tight control on the roads leading out of the camp, so that no service vehicle can be taken out without a permit. (When I was driving back to town with one of the padres, we were held up, despite his cloth, because he could not find his permit.) American military police patrol the town, visit the pubs and dance halls, and at closing time go out also in company with the British police. An American M.P. is permanently on duty at British police headquarters, ready to go as required to any point where there is trouble.

But this sort of co-operation, admirable though it may be, is negative. It is the co-operation between authorities whose main concern is to avoid trouble rather than to create good. It is the ‘play safe’ attitude on their part which, if it were possible, would logically lead to the enforcement of complete segregation. The real opportunity for creating something positive out of the forced community between British and Americans is largely being missed. Friendly relations exist between the Mayor and his officials, and the commanding general and his officers, but this has not led to the wider developments which are possible. This is partly attributable to the American authorities’ natural concentration on the job they are in England to do.

Obsessed as they must be with their-operational requirements, they have, for one reason or another, not responded as fully as they might to the offers that have been made by the various bodies in Warrington. The Education Authority offered to make available a gymnasium which had, in fact, been equipped by the Americans during the war, as a net-ball centre. But the invitation was not even answered. Again, despite the obvious need for close understanding in the vetting of prospective marriages between American servicemen and English girls, some of the padres have still not called on the English opposite numbers of their own denominations. Many difficulties can arise over such marriages, but the answer is not, as suggested by some, the making of a rule that no marriage shall take place till sixty days before the American is due to return home.

Again the Rotary Club sent a warm invitation to Burtonwood for the Americans to visit their homes, but not a single invitation has yet been taken up. Yet the most worthwhile thing that could come out of the presence of these young Americans, all of them volunteers, at Burtonwood, is that they should mix in with the community life of the district. The Commanding General stressed to me how greatly they appreciated the enormous number of invitations from every type of home for his men to spend the Christmas holidays and other weekends in British homes. Many of these were gratefully accepted, and in many cases life-long friendships were started, but in other cases the invitations have not been answered. Of course, the American authorities have rightly felt their responsibility in the matter, and wished to screen their men before accepting such invitations. This may have led to inevitable delay, but none the less one definitely gets the impression that opportunities for positive co-operation have been missed.

On the British side there is the failure to provide a proper centre in Warrington, a sort of Rainbow Comer, where the boys can go in, eat, write letters, play billiards and entertain their girl-friends, in pleasant surroundings. There were a couple of such clubs in Warrington during the war, but unfortunately suitable premises have so far not been found for such a centre. The town authorities have done their best in the matter, but the business has not been treated as one of the first urgency. The fault here is that of the British Government. Edward Porter, the M.P. for

Warrington, has now taken the matter up with the Prime Minister personally.

Is it asking too much of the military and official mind that it should see the whole question of Burtonwood in a broader light? One useful step would be to appoint a senior officer, with the right qualifications, whose sole job should not be just to serve the military ends of the Air Lift, but to develop the positive side which this article suggests. It is admitted that some admirable work is, in fact, being done by the American public relations staff, and especially by the R.A.F. liaison officer at Burtonwood. But the matter requires a far more positive approach, with more thought and planning at a much higher level. Surely it will be found that such effort will not detract from, but will in fact assist, the military objective.

The problem is that of ‘motivation,’ so familiar to industrial psychologists. We are only beginning to tackle the fringes of this problem in industry, and an enormous amount of work has to be done with regard to servicemen. In wartime the motivation is simple enough. It is, to win the war. In peacetime it is less apparent. With the increasingly high standard of education to be found amongst members of the armed forces, whether British or American, much more must be done to stimulate wider interests than purely military ones in the life of a soldier. Though he wears uniform, he is still a citizen of his country, and a human being, with all a human being’s needs.

These young Americans are here in England as members of their country’s fighting forces. Yet the lesson they can learn is that they are here not to make war but to save the peace. It is difficult to condition men to be good soldiers, and at the same time teach them that peace is the greatest prize that anyone can seek in the world today. Yet the need must be faced up to. This perhaps is the main moral to be derived from the story of Burtonwood. The scandal and sensation can drop to their proper proportions. There was never anything very extra-ordinary about it. The real sin is one of omission, of missed opportunities—American and British. There is still the chance there of building something positive and enduring, which will add notably to the world’s store of understanding and goodwill.

==================

Scanned and transcribed by Steven Dowd from a copy of “The Picture Post” published 31st May 1949, I purchased this newspaper a few years ago and never found the time until now to transcribe it into the newton-le-willows website. ©Steven Dowd.2013