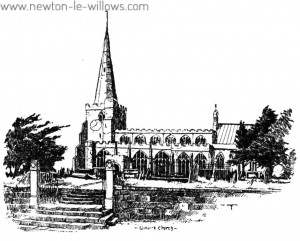

There is no beginning to the istory of Winwick. It goes beyond the Fourteenth Century to the earliest days of the English, to a time “when a King of Mercia was resisting evangelisation with free slaughter; and then, when we seem to have come to the birth of the ancient Saxon village, we see it again in a remoter vista, shining magically in the opal light of legend. The learned Usher thought that Winwick was Caer Gwentquic, one of the twenty cities collected by the monk Gildas out of Nennius; and its modern name is but a corruption of the far-off British original. But if this wonderful vision is too elusive, there is a surer measure of truth in the early Saxon stories that cling to the place. Hereabouts, at Woodhead, was the Palace of Oswald, King of Northumbria in the Seventh Century, who in a great battle at Heavenfield, near Hexham, freed his country from the pagan bondage for a while. But in the year 641 or 642, at Maserfeld, which seems to correspond to the modern Makerfield, “ her Oswald Northanhymbra cyning of slaegen waes,” and his army beaten and scattered by Penda, King of Mercia. Thus, from “win,” a fight, and “wick,” a battle, seems almost certainly to be derived the present name. Oswald’s fate was a characteristic one. His body was hewed in pieces, which were sent abroad for a sign. Most wonderful, surely, of all the church’s relics is the broken Saxon cross which now lies in the churchyard, and which shows the process of dichotomy, and indicates also St. Oswald’s Well, which is the place where the saint was slain, “forth-fared,” as the splendid Saxon word says.

Rector – Rev. O. H. L. Penrhyn.

Curate – Rev. A. Inglie.

Churchwardens – Mr. Albert Kilahaw and Mr. W. Massey.

Sidesmen – Hr. J. W. Pennington, Mr. W. Stanier, Mr. E. Warburton, and Mr C. Gerosa.

Vestry Clerk – Mr. J. E. Pettener.

Lay Representatives – Mr. R. Stone and Mr. J. W. Pennington.

Interesting Discoveries.

Yet there is an even more certain evidence of a still greater antiquity than this. Several years ago some labourers, working by the side of a bye-lane about half a mile io the east of | Winwick Church, struck a spade into an urn, containing bones and with them a stone hammer head and a bronze dart. Some years previously two barrows near the same lane had been trenched, and many bones, with fragments of flint, were found. Even more awe-inspiring was a discovery made in 1828. The present church stands by the side of the road on a high hill, and there is a tradition that the church was the site of a Druidical altar and place of sepulture in the dimmest of dim ages. In 1828 there was digging under the church, and there, at a depth of eight or ten feet below the floor, and buried under a heap of great sandstone blocks, were found three gigantic human skeletons, laid over one another and coffinless.

The Sunshine.

Yet one thinks not so much of these things on a clear and sunny afternoon. From Warrington to Winwick is first a mile train ride— tho line stops bewilderingly in the exact middle of nowhere—and, then, half-an-hour’s. walk for an eager pilgrim. The last part of the journey is the best, for in .Warrington, and about Warrington, there are smells.

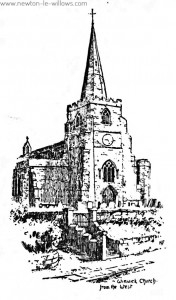

It is not long before the church tower, wonderfully high above the trees, comes in sight, and stays in sight, though it circles and shifts as the road winds. Presently one passes cottages built anciently on sandstone, with blowing gardens, and then one passes Broad Oak Cottage, which is Elizabethan and peaceful, and set about with lawns and flowers and trees. And here one sees the whole vision of the venerable church. A terrace steps upward many feet to the churchyard, which rises still to the church itself. The tower is gray with its own age, and chipped and flinted by the passage of the years. It stands out squarely from the rest of the fabric, which is old as well, but not so old as this. The churchyard wall is a triangle, with the flattened apex nearest to us, and an obelisk in keeping stands on a wedge of green by the quiet gate. The road divides to left and right, but leafy lanes, cutting across the fields and down pleasant avenues of trees link it up here and there. The grass is long in the churchyard, and this and the brown and ancient gray of the gravestones give a tranquil evenness of aspect to the sight. Peace, and sunshine, and beauty, are over the place.

Concerning the Pig.

The story of Winwick Church is, above all, a story of bygones. In the days of its greatness the parish had a big population, and it included a country which is now cut up into eight separate parishes and chapelries. Now its population is about seven hundred. The church itself shows its weavings in the web of time. In local tradition it begins with the Pig; and very firmly is the Pig established. On one side of the tower are three niches, one great, and the others, fixed on each side, smaller. The middle niche and one of the others are empty, but the third has been sheltering the Pig from wind and weather for a little less than a thousand years. It is told that the intention was to build the church on Hermitage Green, but that each night a Pig tumbled the stones to the present site. till the builders altered the place of the building. The only remarks the Pig ever made during all his labours were “ Win-wick, Win-wick,” and this intelligent commentary on topical affairs was remembered when a name was sought for the parish. But, as a mere matter of fact, the middle niche was once filled by St. Anthony, the swineherd; and the Pig should be accounted a figure of pathos. The church rests mediately on Saxon foundations, but the present fabric is, in its eldest parts, of Normal build. The first of it was the Haydock chantry chapel, which was built of red stone in 1330, a hundred and thirty-eight years, it should be remembered after the date of the first Norman rector. The steeple and the body of the church were built about the year 1358, but in the base of some of the pillars of the north aisle there is the sculpture of a bishop’s head. Tho mitre he bears was in use in the Twelfth Century; and the pillars were part of an earlier Saxon church which stood there. With many another it was likely torn down by the Normans as they worthily wasted the North country. To separate the history of the various parts of the church is a bewildering business for breaking and building never seem to have been stayed.

The Making of History

The first of the Church’s sorrows was the Norman Conquest, and the second was surely the Civil War. Since its Norman incarnation it had gone on a third antiquity if one counts the pre-Saxon times as one period, and the Saxon times as another. Quite a large number of members of local families had been buried within its walls, and left a hint of their importance in the brass tablets which they put up plentifully. In tho Gerard is one that tells the Twentieth Century of Piers Gerard who died in 1492. The tide of things has given it more interest than it would otherwise have had, for the Gerards stood by the older faith in the days of the Reformation, and Piers would be an alien now. In 1530 the south wall had been rebuilt, with disastrous results to the tracery of the windows. At the same time, the architect tried to make the south wall like that on the north, but he failed, for be made it better, the pillars and arches of the one being moulded, while those of the other are plain, even very plain. The five tableted buttresses on the north side still stay, but their decorations are matters of conjecture, though the corbel heads on the windows are as grotesque as ever they were. A little time later came the first rumours of the Reformation, bringing the abolition of the chantry priest of this church, as of all other churches. In the same year, 1553, was the Grammar School of Winwick founded, one of those who had an executive part in its foundation being Thurstan Tyldesley, M.P. for Lancashire, and Feoffee of the Grammar School of Manchester in its first years. The fourth of its masters was a remarkable man. He, himself, had been one of the early scholars, but at fifteen he changed his business to that of master. Later, he was ordained; was a teacher at Toxteth Park, Liverpool, of Jeremiah Horrox, the wonderchild of English astronomy; and in 1635, being prescribed as a Puritan, he made the journey to New England. The name of Increase Mather, his son is famous; and that of Cotton Mather, his witch-burning grandson, duly infamous.

The WOES of WINWICK.

Both Winwick and Warrington were Royalist, and, while Warrington got into fighting array, Winwick Hall was also provisioned and fortified. Either on the twenty-fifth or on the twenty-third of May, in 1643, the Puritans stormed the Hall; and on the same day the church steeple, where a defence had been made. One of the defenders took it into his head to parley from the church steeple, until, according to a local story, he was shot, and fell. In 1854, while a grave was being dug near to the steeple, a skeleton was found, with an iron bullet in the thigh bone. The discovery was a grim rounding off of the storv. The Cromwellians seem to have thoroughly grasped the privileges of victory while they stayed here. Tradition tells – and tradition, in such a curious and enclosed place, is worth more than elsewhere – that they stabled their horses in the church. At any rate, so much as had been left of the window tracery they did utterly destroy, and it was probably not untrue that they watered their horses from the font. They marched away, but Winwick had not seen the last of them. Winwick Hall was sequestrated, to encourage the others, one supposes. Five years later, the terrible Cromwell himself was here, spending three days in beating the Duke of Hamilton. On the 19th of August they broke and fled, after great slaughter. Of all these who died, only one, Major John Cholmley, Carlyle’s “little spark in a blue bonnet,” was buried, and his grave is in Winwick Churchyard. In the church the prisoners were paraded, and disarmed. You may be told yet, quite seriously, of the ghostly Highlanders who march terrifically by Red Bank. In August of 1651 doom stalked by two of the men in the Royal procession which passed through Winwick, and two of the greatest: the King and the Earl of Derby. But a little later they had both died on scaffolds, one at Bolton, as the stained glass window of Winwick Church reverently reminds us.

A HEALING Peace.

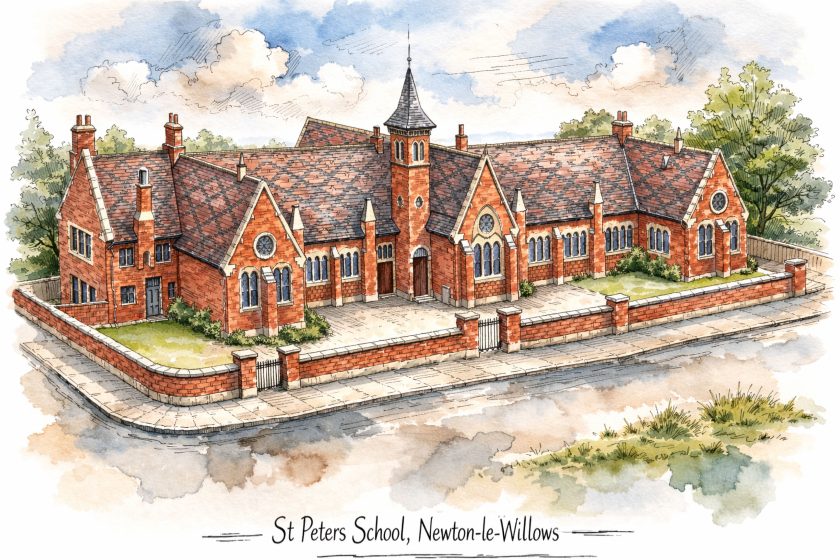

For a hundred years after this the nearest hint of war is the statement, in the Church register, that 2s. 6d. and 4s. were given by John Worsley and James Sorrocold to Mary Englefield towards ransoming her husband from the Turks; and a further account that in 1745 a dctachment of Scottish rebels found their way from Wigan to Winwick, and heroically stole all they could lay their hands on. Besides its recovery from its hurts during the Civil War it began to undergo other changes. The roof has a date of 1701 on it, and we know, by the churchwardens’ own proclamation, that the south porch was built in 1721. So long the Parish of Winwick, with its four chapelries of Ashton – Lowton, St. Peter’s, Newton, and Newchurch – and its nine townships, each larger than an ordinary parish in the South of England, had been like a little diocese. But in 1845 the Rev. James John Hornby, whose brother had obtained distinction at the beginning of the century in the battle of Lissa, and had become a knight, an admiral, and one of the Lords of the Admiralty, resolved to divide the parish into a number of smaller and separate parishes. Two years later another of his works, the re-building of the chancel, under the directions of Welby Pugin, was finished, as fitting monuments record. He died in 1855, and was buried at Winwick, where he was born; but the work of restoration went on after him, and was completed in 1858. Among its treasures is an ancient and beautiful rood screen. It had been taken from the church during the Civil War, and was found on a cottager’s hearth some years ago.

Present History. ,

Shortest of all that can be said of Winwick is its recent story. Shorn of its most populous parts, its congregations are not great ones. There is not a single poor person in the parish, and so there is not any benevolent organisation of any sort, except a few ancient charities. And, because the parish is so spread about, there is not a single guild, or maternal meeting, or any such thing. The Sunday school stays, and its hundred and twenty children walk there, to their great gain, on each Sunday. Perhaps the most stirring of the late annals of the parish is the story of the kindly gift of the Quakers of Warrington. A churchwarden, falling in love with some candelabra they had, reported it to the church, and overtures for purchase were made. But the Quakers declined to sell. What they did was to make a gift of the candelabra, on condition that there should be no graven record of their giving. For all that they will be remembered for a very long time. Here, amid the quiet splendour of an ancient peace, one feels that the beauty of the giving is even as great as the beauty of the thing given.